The curated resources linked below are an initial sample of the resources coming from a collaborative and rigorous review process with the EAD Content Curation Task Force.

Reset All

Reset All

This lesson has students examine the freedoms provided in the First Amendment through video-based resources and a choice board.

The Roadmap

C-SPAN Television Networks/C-SPAN Classroom

The phrase “a house divided” comes from Abraham Lincoln’s speech to the Illinois Republican State Convention in 1858, when he describes a nation so badly torn between those that permitted slavery and those that prohibited it that it was on the brink of war. While the issue of slavery is understood to be central to the start of the Civil War, this set of resources is intended to introduce students to more details of the growing tension in the nation. Resources include information and images about expanding territory and the addition of new states to the union; voices of the abolitionist movement; political tension and acts of violence. It does not provide comprehensive coverage of these decades, but it helps to highlight that the growing tension was both multifaceted and happening across the entire nation.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by Decade1830s (4)1840s (3)1850s (9)

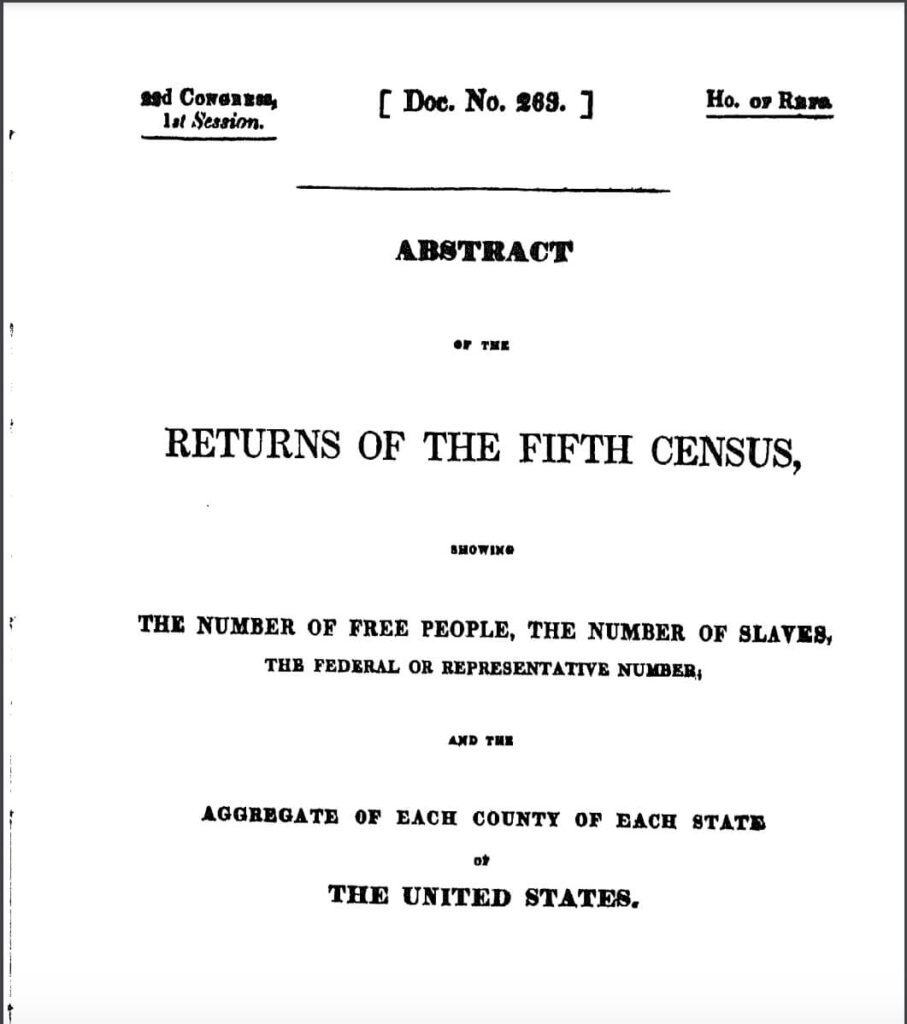

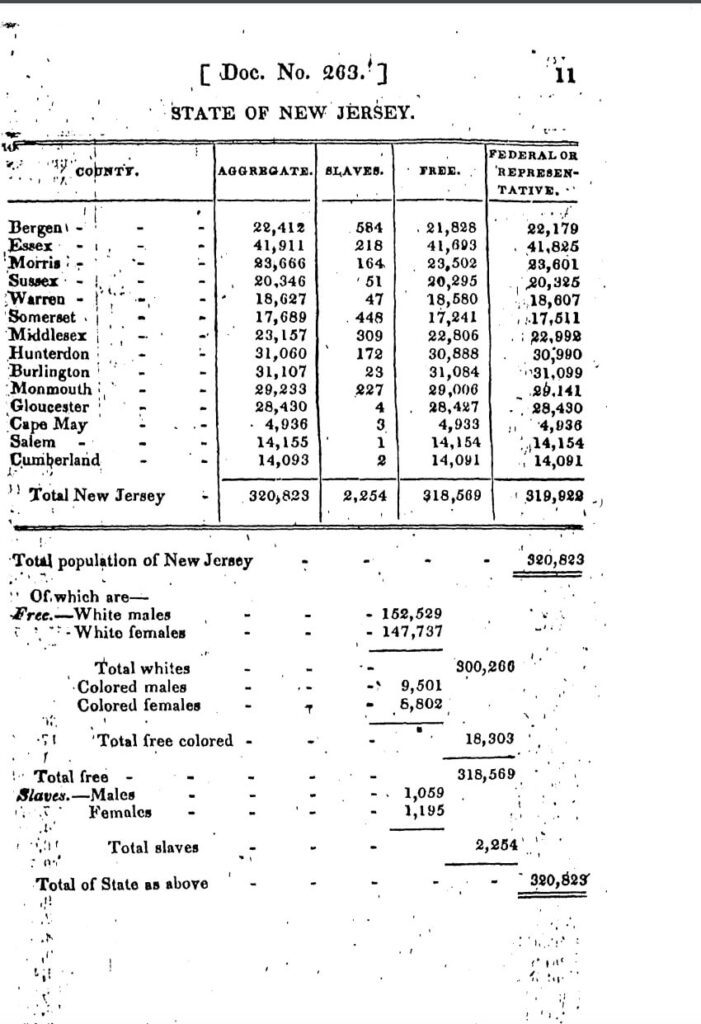

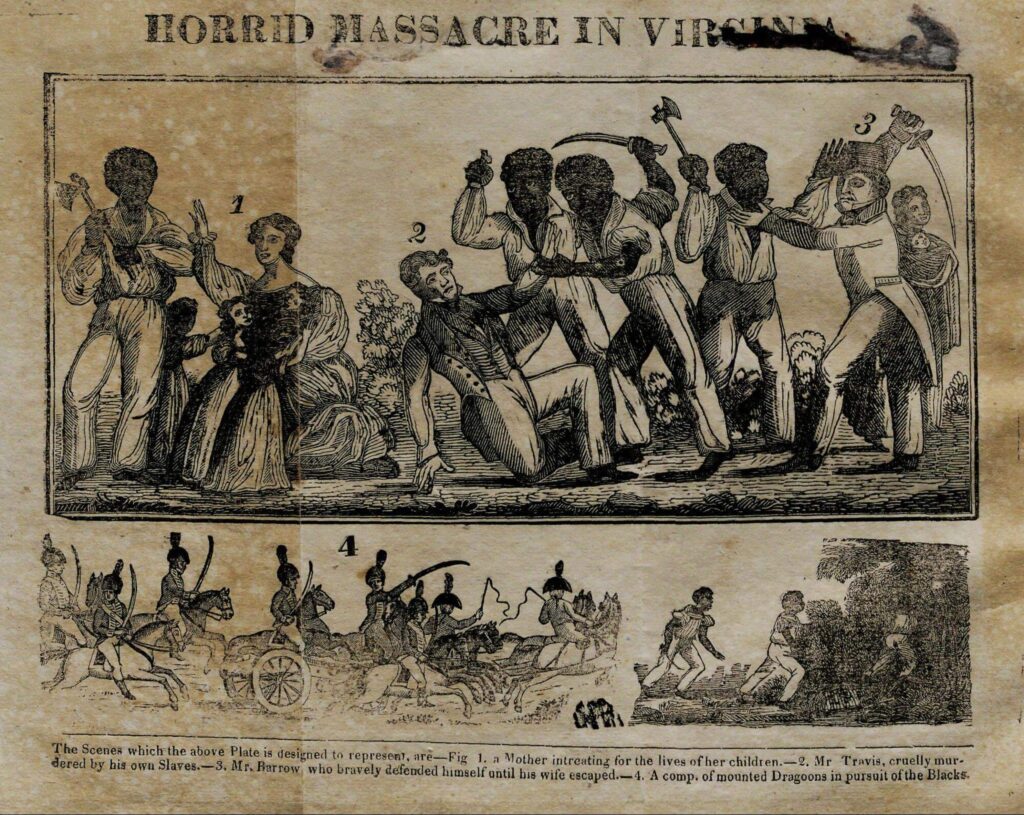

- All 16 Primary ResourcesThe Census of 1830

This abstract of the Census from 1830 not only provides numbers, state by state, of free and enslaved persons – but students will note that there are enslaved persons in many of the states they consider “free” (sample pages at left).

Note that the terminology is historically accurate but might be offensive to students unless context is provided (this will be true for many of the documents from this era).

CitePrintSharehttps://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1830/1830b.pdf

ORIIN, DUFF. “1830 Census - Full Document.” Census.gov, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1830/1830b.pdf.

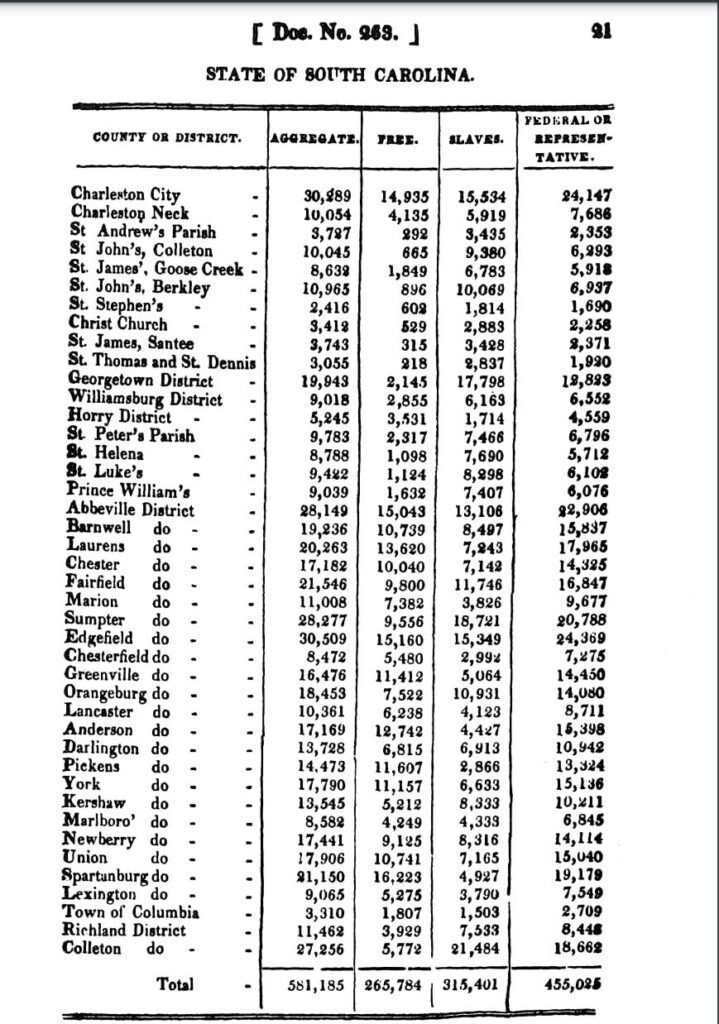

Nat Turner’s Rebellion, 1831Transcript“Even though Turner and his followers had been stopped, panic spread across the region. In the days following the attack, 3000 soldiers, militia men, and vigilantes killed more than one hundred suspected rebels. …Nat Turner’s rebellion led to the passage of a series of new laws. The Virginia legislature actually debated ending slavery, but chose instead to impose additional restrictions and harsher penalties on the activities of both enslaved and free African Americans. Other slave states followed suit, restricting the rights of free and enslaved blacks to gather in groups, travel, preach, and learn to read and write.” (Gilder Lehrman, link at right.)

Nat Turner’s Rebellion led to both public debate and a tightening of laws and policies. “Nat Turner was an enslaved man who had learned to read and write and become a religious leader despite his enslavement; following what he took to be religious signs, he led other enslaved people in an armed uprising. The violence of the uprising and Turner’s ability to escape and hide for approximately six weeks following the event led to changes in laws and policies and also led to a widespread climate of fear among white slaveholders. Enslaved people in far-flung states who had no connection to the event were lynched by white mobs. The State of Virginia briefly considered ending the practice of slavery in the wake of the rebellion, but they ultimately decided instead to tighten the laws of slavery.

1Africans in America/Part 3/Nat Turner's Rebellion. (n.d.). PBS. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part3/3p1518.html and Nat Turner - Rebellion, Death & Facts - HISTORY. (2021, January 26). History.com. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/nat-turnerCitePrintShareAllyn, Nelson. “Nat Turner's Rebellion, 1831 | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History |, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/nat-turner%E2%80%99s-rebellion-1831.

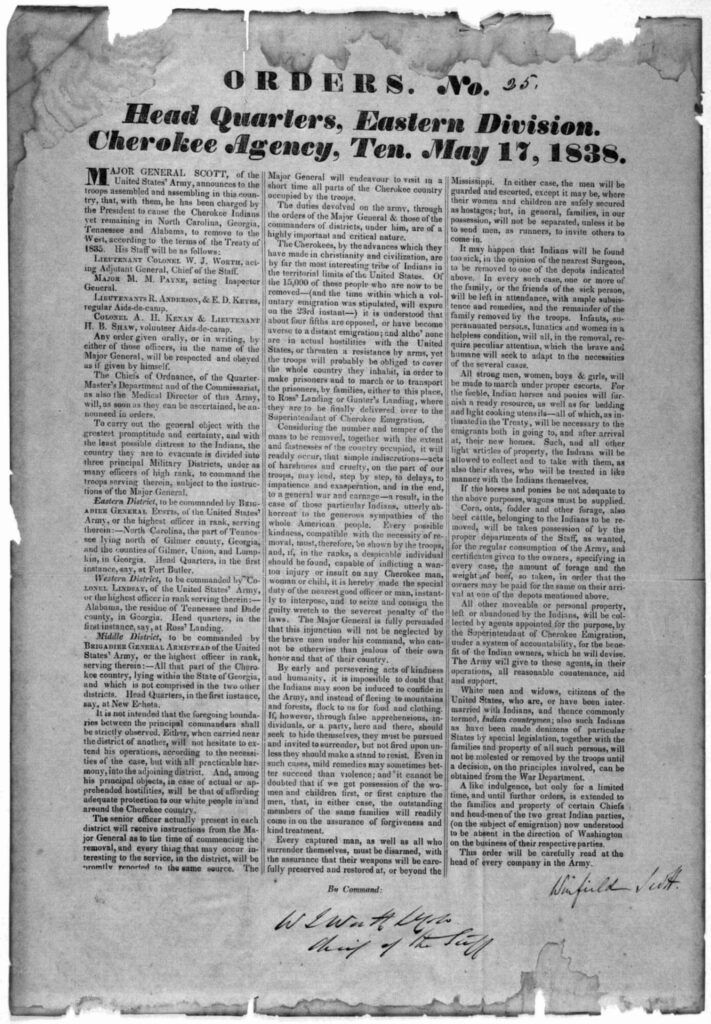

Orders pursuant to the Indian Removal Act of 1830 (Trail of Tears)Orders pursuant to the Indian Removal Act of 1830 (Trail of Tears)While the Trail of Tears and “Indian Removal Act” are not central to understanding slavery, they are critical events in the history of the country in this era; in addition, the concept of “indian removal” connects directly to tensions that rose as the nation expanded in both population and territory.

As the United States acquired Western territories, and as the power battle between slaveholding and free states continued, the land on which Native nations lived became increasingly valuable. After President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Choctaw, Creek, and Cherokee nations were forced to move from their land, most often on foot and with the deaths of many people, into Western territories. The 1838 forced removal of the Cherokee people from their Georgia land led to the deaths of thousands of people (exact numbers are unknown, but estimates range around 4,000 - 5,000.)

1- History & Culture - Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail (US National Park Service). (2020, July 10). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/trte/learn/historyculture/index.htm and Trail of Tears: Indian Removal Act, Facts & Significance - HISTORY. (2020, July 7). History.com. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/trail-of-tears

CitePrintShare“Tile.loc.gov.” Library of Congress, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/rbc/rbpe/rbpe17/rbpe174/1740400a/1740400a.pdf.

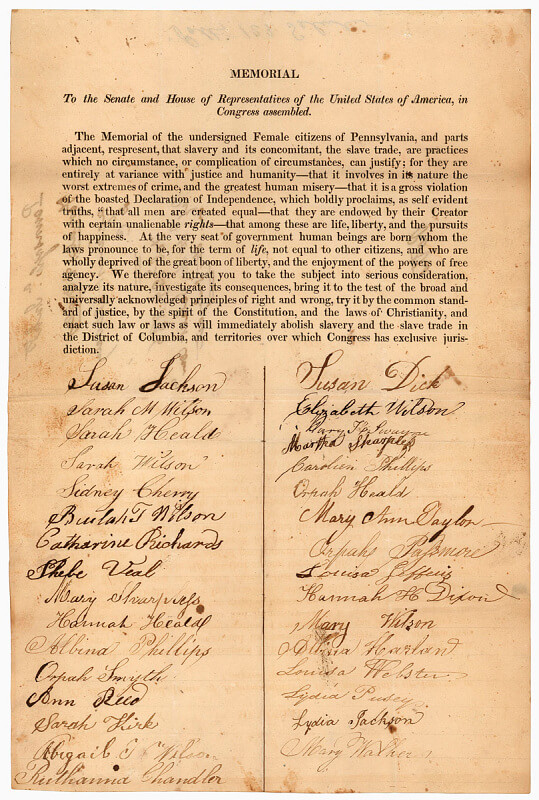

The Gag Rule, 1836“On May 26, 1836, the House of Representatives adopted a ‘Gag Rule’ stating that all petitions regarding slavery would be tabled without being read, referred, or printed….The enactment of the Gag Rule, rather than discouraging petitioners, energized the anti-slavery movement to flood the Capitol with written demands. Activists held up the suppression of debate as an example of the slaveholding South’s infringement of the rights of all Americans.”

CitePrintShareAdams, John Quincy. “The Gag Rule | National Museum of American History.” National Museum of American History, https://americanhistory.si.edu/democracy-exhibition/beyond-ballot/petitioning/gag-rule.

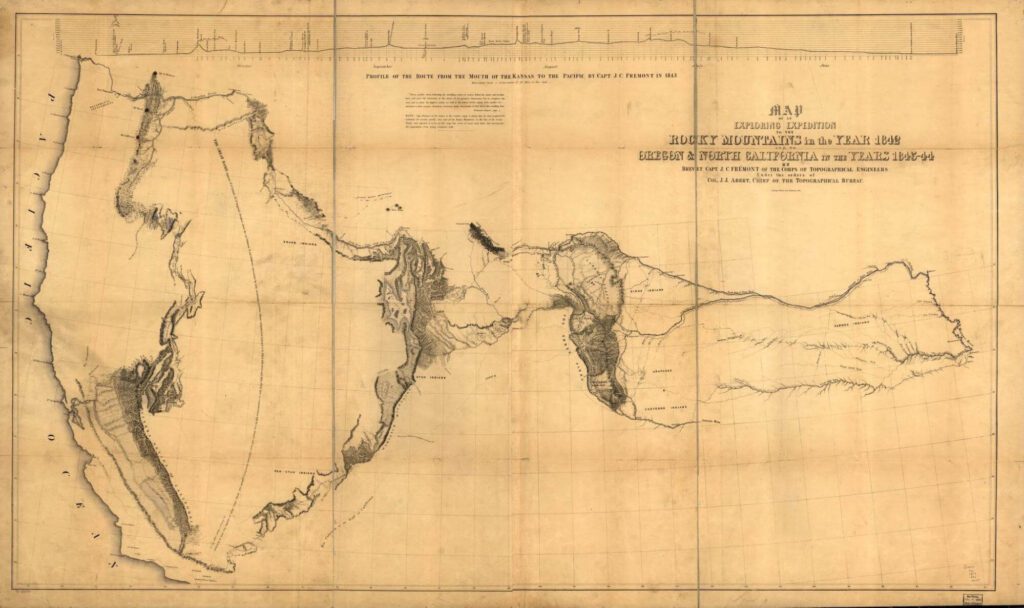

Map of Westward Expedition and Expansion, 1842-44Map of an exploring expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the year 1842 and to Oregon & north California in the years 1843-44As the nation expanded Westward, tensions rose further over whether new states and territories would permit or prohibit slavery.

CitePrintShareMap of an Exploring Expedition to the Rocky ... - Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4051s.ct000909/.

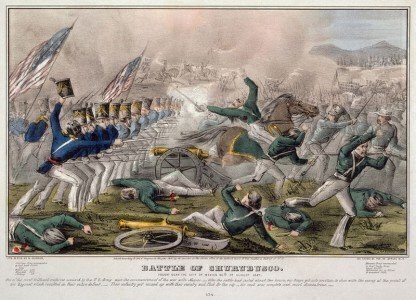

Battlefield Painting, Mexican-American WarBattlefield Painting, Mexican-American War“The pact set a border between Texas and Mexico and ceded California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming to the United States. …the acquisition of so much territory with the issue of slavery unresolved lit the fuse that eventually set off the Civil War in 1861.”

CitePrintShare“The Mexican-American war in a nutshell.” National Constitution Center, 13 May 2021, https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/the-mexican-american-war-in-a-nutshell.

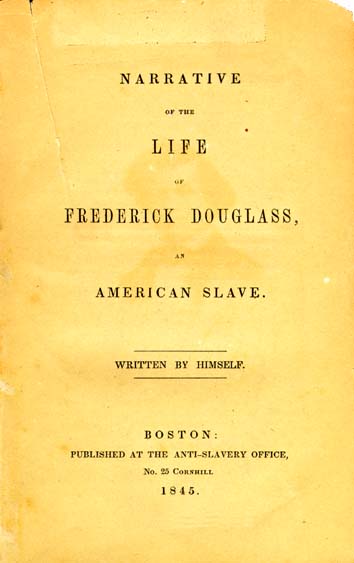

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, excerpt, 1845TranscriptCHAPTER I. I WAS born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about twelve miles from Easton, in Talbot county, Maryland. I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it. By far the larger part of the slaves know as little of their ages as horses know of theirs, and it is the wish of most masters within my knowledge to keep their slaves thus ignorant. I do not remember to have ever met a slave who could tell of his birthday. They seldom come nearer to it than planting-time, harvest-time, cherry-time, spring-time, or fall-time. A want of information concerning my own was a source of unhappiness to me even during childhood. The white children could tell their ages. I could not tell why I ought to be deprived of the same privilege. I was not allowed to make any inquiries of my master concerning it. He deemed all such inquiries on the part of a slave improper and impertinent, and evidence of a restless spirit. The nearest estimate I can give makes me now between twenty-seven and twenty-eight years of age. I come to this, from hearing my master say, some time during 1835, I was about seventeen years old.

Students would benefit from reading an excerpt of the text of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass – but in addition, the cover itself is an interesting artifact, and students can discuss its details and its possible impact upon publication in 1845. (See also text in this chart, below, from Frederick Douglass’ July 4 address in 1852.)

CitePrintShareHempel, Carlene, et al. “Frederick Douglass, 1818-1895. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself.” Documenting the American South, https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/douglass/douglass.html.

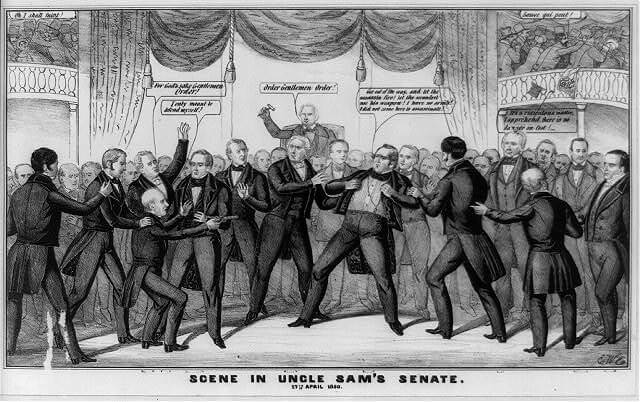

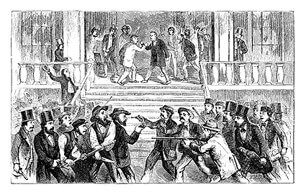

Scene in Uncle Sam’s Senate, 1850“Scene in Uncle Sam's Senate.Transcript"A somewhat tongue-in-cheek dramatization of the moment during the heated debate in the Senate over the admission of California as a free state when Mississippi senator Henry S. Foote drew a pistol on Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri.”

As new states were added to the nation, the question of how many would permit slavery and how many would prohibit it – and, therefore, which faction had more power – continued to contribute to growing tension.

CitePrintShare“Scene in Uncle Sam's Senate. 17th April 1850.” The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2008661528/.

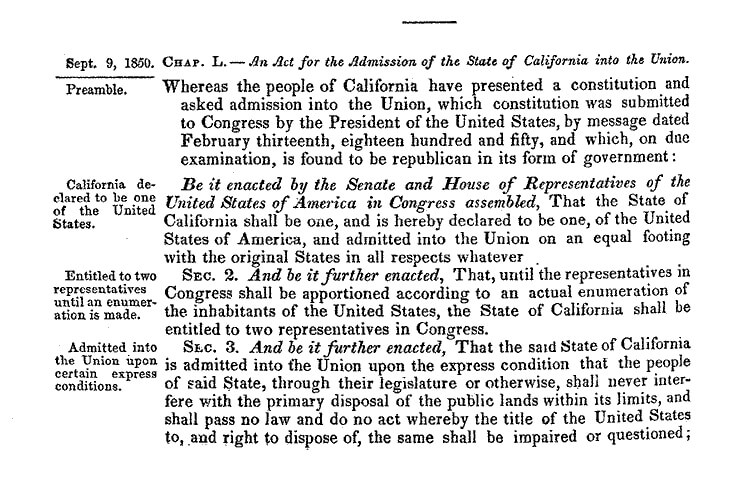

An Act for the Admission of the State of California into the Union, 1850CitePrintShareA Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875, https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=009%2Fllsl009.db&recNum=479.

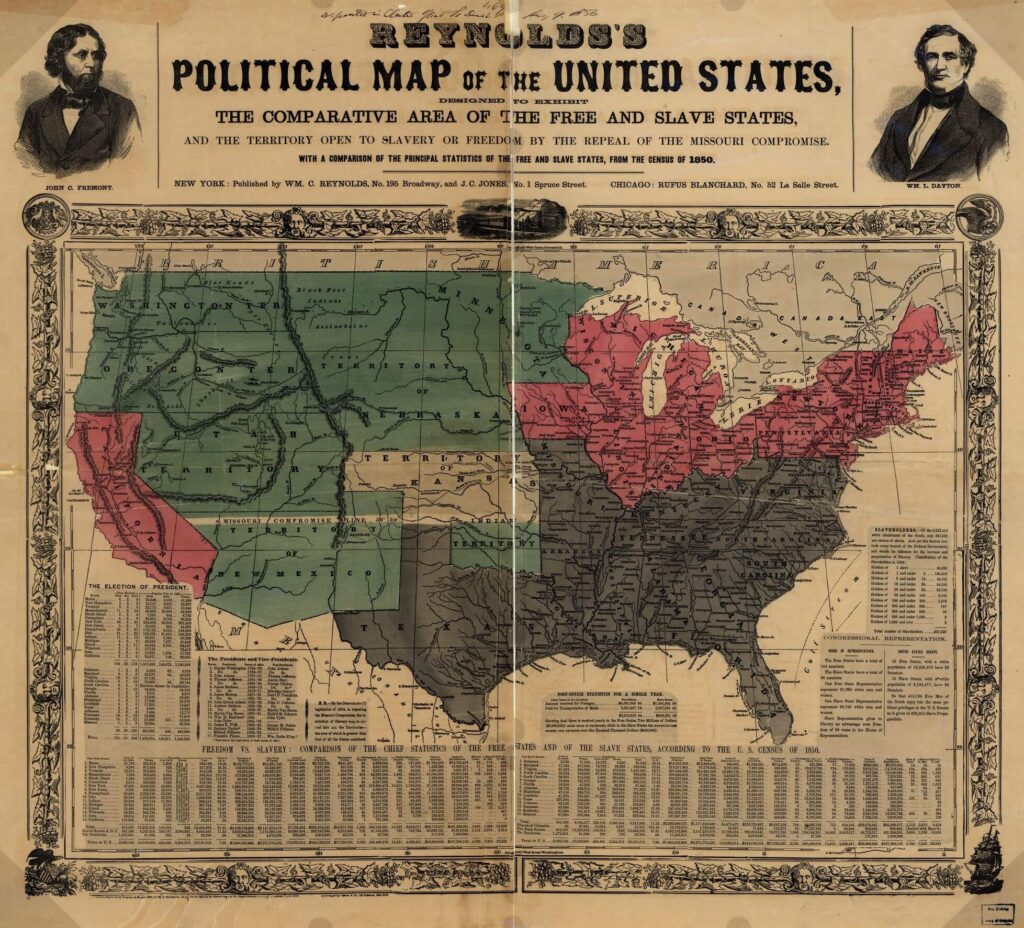

Political Map of the United States in 1850Political map of the United States in 1850This map has a range of valuable information, not only about Presidential politics, but also about population statistics and slavery. It makes a particular point of comparison with the 1830 Census, hyperlinked above in this chart.

CitePrintShare“1850 Political Map of the United States - History.” U.S. Census Bureau, 9 December 2021, https://www.census.gov/history/www/reference/maps/1850_political_map_of_the_united_states.html.

Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”, 1852Douglass raises critical questions about patriotism, citizenship, and the nation’s ideals in this address. The text highlights issues that will continue to be points of tension not only at the start of the Civil War, but throughout Reconstruction (and, truly, throughout American history).

“I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us. I am not included within the pale of glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

- Frederick Douglass, July 5, 1852CitePrintShareJuly 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass keynote address at an Independence Day celebration: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

“A Nation's Story: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”” National Museum of African American History and Culture, 3 July 2018, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/nations-story-what-slave-fourth-july.

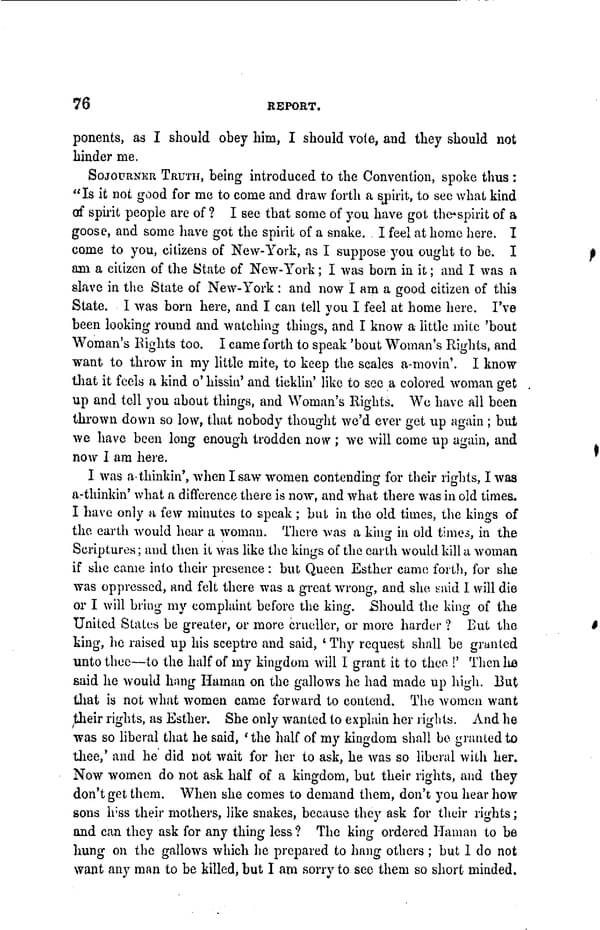

Sojourner Truth, Photograph and Speech at the Women’s Rights Convention, 1853See above; understanding the life and words of Sojourner Truth helps students to understand the complexity and intersectionality of both the women’s rights movement and the abolitionist movement.

CitePrintShareTitle Proceedings of the Woman's Rights Convention held at the Broadway Tabernacle, in the city of New York, on Tuesday and Wednesday, Sept. 6th and 7th, 1853.

Summary Sojourner Truth addresses the convention.

Image 76 of Susan B. Anthony Collection Copy | Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbnawsa.n8289/?sp=76.

“Bleeding Kansas,” 1858“The years of 1854-1861 were a turbulent time in Kansas territory. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 …allowed the residents of these territories to decide by popular vote whether their state would be free or slave. This concept of self-determination was called popular sovereignty'. …Three distinct political groups occupied Kansas: pro-slavers, free-staters and abolitionists. Violence broke out immediately between these opposing factions and continued until 1861 when Kansas entered the Union as a free state on January 29th. This era became forever known as ‘Bleeding Kansas’.” (National Park Service, link at right.)

CitePrintShare“Bleeding Kansas - Fort Scott National Historic Site (US National Park Service).” National Park Service, 23 April 2020, https://www.nps.gov/fosc/learn/historyculture/bleeding.htm.

Abraham Lincoln, “A House Divided” Speech, 1858This excerpt from (or the entirety of) Lincoln’s address to the Republican State Convention puts the notion of “a house divided” in its original context, just before the start of the Civil War.

NOTE: Because it provides the central concept of this set of resources, I’ve included it last (although it predates John Brown’s speech above.)

Illinois Republican State Convention, Springfield, Illinois June 16, 1858Abraham Lincoln

Mr. President and Gentlemen of the Convention. If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do, and how to do it.

We are now far into the fifth year, since a policy was initiated, with the avowed object, and confident promise, of putting an end to slavery agitation. Under the operation of that policy, that agitation has not only, not ceased, but has constantly augmented.

In my opinion, it will not cease, until a crisis shall have been reached, and passed -

"A house divided against itself cannot stand."

I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.

I do not expect the Union to be dissolved - I do not expect the house to fall - but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.

1- John Brown's Raid (US National Park Service). (2021, July 30). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/articles/john-browns-raid.htm

- John Brown's Raid on Harper's Ferry. (n.d.). Ohio History Central. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/John_Brown%27s_Raid_on_Harper%27s_Ferry

CitePrintShare“House Divided Speech - Lincoln Home National Historic Site (US National Park Service).” National Park Service, 10 April 2015, https://www.nps.gov/liho/learn/historyculture/housedivided.htm.

An excerpt from John Brown's address to the court after hearing his guilty verdict, 1859John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry fits into Lincoln’s foretelling of a crisis and further spurs the start of the Civil War. Brown’s speech to the courtroom highlights his sense of what, in this moment, constitutes justice and injustice.

John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry: John Brown, an abolitionist, led the Raid on Harper’s Ferry, a federal arsenal, in an effort to start an armed insurrection against slavery. The event, which took place after Lincoln’s “a house divided” speech, serves as an example of the violence Lincoln foretold. Brown echoed Lincoln’s sentiments, explaining in 1859, “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.” Brown and his followers were trapped and arrested, and Brown was tried and found guilty of treason.

“I have, may it please the court, a few words to say. In the first place, I deny everything but what I have all along admitted--the design on my part to free the slaves. I intended certainly to have made a clean thing of that matter, as I did last winter when I went into Missouri and there took slaves without the snapping of a gun on either side, moved them through the country, and finally left them in Canada. I designed to have done the same thing again on a larger scale. That was all I intended. I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.I have another objection; and that is, it is unjust that I should suffer such a penalty. Had I interfered in the manner which I admit...had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends--either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class--and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.”

CitePrintShare“An excerpt from John Brown's address to the court after hearing his guilty verdict, 1859.” Digital Public Library of America, https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/john-brown-s-raid-on-harper-s-ferry/sources/1722.

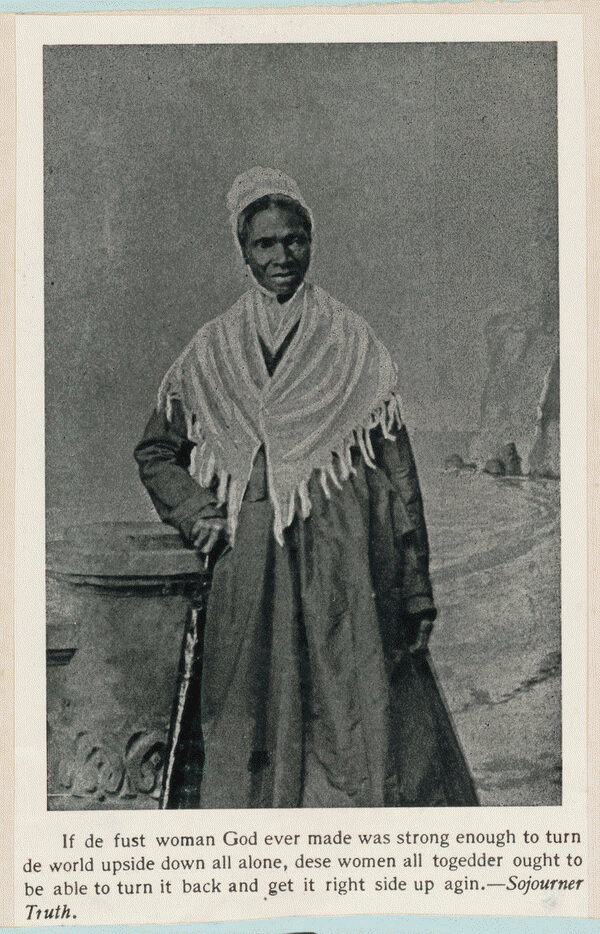

The Women’s Rights Convention of 1853TranscriptQuotation beneath the photograph: "If de fust woman God ever made was strong enough to turn de world upside down all alone, dese women all togedder ought to be able to turn it back and get it right side up agin."

This photograph pairs with the text in the row below from the Women’s Rights Convention of 1853, when Sojourner Truth spoke to the group.

The Women’s Rights Convention: The Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 is a significant event in the fight for women’s rights and for women’s suffrage, though activists at the convention itself debated whether suffrage should be the center point of their platform. In addition, the Seneca Falls Convention is now widely understood to represent some tension between the women’s rights movement and the abolitionist movement; some activists at the time felt that the right to vote should not go to black men before white women. In this collection of documents, Sojourner Truth’s speech to a smaller, subsequent convention – one held in New York in 1853 – is included, largely because of the critical role Sojourner Truth plays in demonstrating the importance of the intersectionality of both the women’s rights and abolitionist movements.

1- On this day, the Seneca Falls Convention begins. (2021, July 19). National Constitution Center. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/on-this-day-the-seneca-falls-convention-begins and More Women's Rights Conventions - Women's Rights National Historical Park (US National Park Service). (n.d.). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/more-womens-rights-conventions.htm and Proceedings of the Woman's Rights Convention held at the Broadway Tabernacle, in the city of New York, on Tuesday and Wednesday, Sept. 6th and 7th, 1853. (n.d.). Library of Congress. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.loc.gov/item/93838289/

CitePrintShare“Sojourner Truth.” The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/rbcmiller001306/.

Education for American Democracy

This free curriculum guide from the New-York Historical Society illuminates the stakes of the American Revolution through a study of the largest single battle of the Revolutionary War.

The Roadmap

New-York Historical Society

In this curriculum unit, students look at the role of President as defined in the Constitution and consider the precedent-setting accomplishments of George Washington.

The Roadmap

National Endowment for the Humanities

The mobile app is an interactive learning tool for tablets that situates the user in the proposals, debates, and revisions in Congress that shaped the Bill of Rights. Its menu-based organization presents a historic overview, a detailed study of the evolving language of each proposed amendment as it was shaped in the House and Senate, a close-up look at essential documents, and opportunities for participation and reflection designed for individual or collaborative exploration.

The Roadmap

National Archives Center for Legislative Archives

Run your own law firm specializing in Constitutional law and determine whether clients have a right, match them with the best lawyer, and win the case!

The Roadmap

iCivics, Inc.

All humans are born with equal inherent rights, but many governments do not protect people's freedom to exercise those rights. The way to secure inalienable rights, the Founders believed, was to consent to giving up a small amount of our freedom so that government has the authority to protect our rights. Freedom depends on citizens having the wisdom, courage, and sense of justice necessary to take action in choosing virtuous leaders, and in holding those leaders to their commitments.

The Roadmap

Bill of Rights Institute

With ever-evolving media, visual images play a significant and powerful role in moments of social change. This spotlight kit, made up almost entirely of primary source images ripe for visual analysis, focuses on moments of protest and resistance to government policies and other symbols of authority. Resources include images of events, movements and moments of resistance from the mid-20th to the early 21st centuries. In these moments, photographs and other media play the dual role of capturing the message and, in helping to spread its visibility, contributing to the fight for social change.

This image-based Spotlight Kit lends itself particularly well to a range of uses in the classroom: as an inquiry activity to introduce an historic era or the theme of protest; with diverse learners, including students with identified language processing disorders or students who are English Language Learners; and as a supplement to other text-based primary sources.

While no set of images can comprehensively capture any era, these particular examples were selected for their intentional use of visual media or the ways in which these moments have become symbolic and iconic. The images also include powerful slogans used by activists, many of which connect and echo across different events in this collection.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by Decade1955-1960s (4)1970s-1980s (7)2000-2022 (10)

- All 21 Primary ResourcesMamie Till Mobley weeps at her son's funeral (1955)Mamie Till Mobley weeps at her son's funeral on Sept. 6, 1955, in Chicago. Mobley insisted that her son's body be displayed in an open casket forcing the nation to see the brutality directed at Blacks in the South. AP, FILE

Following the lynching murder of her fifteen-year-old son, Emmett Till,, Mamie TIll Mobley insisted on an open casket at his funeral; according to Time magazine, “When Till’s mother Mamie came to identify her son, she told the funeral director, ‘Let the people see what I’ve seen.’” The graphic images of his beaten body captured the attention of people across the United States, and the photo’s publication in Jet magazine is widely considered a galvanizing moment for the Civil Rights Era.

CitePrintShareShapiro, Emily. “Emmett Till's childhood home is named a Chicago landmark.” ABC News, 28 January 2021, https://abcnews.go.com/US/emmett-tills-childhood-home-named-chicago-landmark/story?id=75536520.

“The Photo That Changed the Civil Rights Movement.” TIME, 10 July 2016, https://time.com/4399793/emmett-till-civil-rights-photography/.

The March on Washington (1963)The March on Washington, 1963The March on Washington, 1963 By 1963 the Civil Rights Movement had grown substantially. They had support for both the black and white communities, as well as many celebrities. The purpose of this march was to gain national support for legislation in Congress. One of the most famous moments of the march was Dr. Martin Luther King Jr.'s “I Have a Dream” speech. Originally proposed in 1941 as the “March for Jobs and Freedom” by A. Philip Randolph, photographs of the March became – and remain – some of the most iconic images of the Civil Rights Movement.

CitePrintShareLeffler, W. K., photographer. (1963) Civil rights march on Washington, D.C. / WKL. Washington D.C, 1963. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003654393/.

Memphis Sanitation Workers’ Strike (1968)US National Guard troops block off Beale Street in Memphis, Tennessee, as civil rights protesters march for the third day in a row. Bettmann/Getty Images (March 29, 1968)Any number of images from the Civil Rights era would benefit a unit on freedom of speech, but this particular image does a few things: (1) it marks the occasion immediately before Martin Luther King’s assassination; (2) it provides an image of a single text used over and over, in contrast to the image above with multiple demands; and (3) it juxtaposes protesters exercising their first amendment rights with National Guard troops wielding weapons.

CitePrintShare“1968: The year in pictures.” CNN, https://www.cnn.com/interactive/2018/05/world/1968-cnnphotos/. Accessed 26 February 2023.

John Carlos and Tommie Smith raise fists in protest as they receive their Olympic medals (1968)John Carlos and Tommie Smith raise fists in protest as they receive their Olympic medals (1968)Aware of the platform provided by international television coverage of the Olympics, medal-winning U.S. track athletes John Carlos and Tommie Smith chose to raise a fist during their medal ceremony to protest racial inequality in the country they were representing, at the very moment the Star Spangled Banner was playing.

CitePrintShareLayden, Tim. “John Carlos, Tommie Smith: 1968 Olympics black power salute.” Sports Illustrated, 3 October 2018, https://www.si.com/olympics/2018/10/03/john-carlos-tommie-smith-1968-olympics-black-power-salute.

Women's Strike for Peace and Equality (1970)Women's Strike for Peace and Equality, New York City, Aug. 26, 1970. Eugene Gordon—The New York Historical Society / Getty ImagesThe 1970s Women’s Strike was organized by feminist author Betty Friedan, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of the 19th Amendment, which prevented women from being denied the vote “on the basis of sex.” As reported by Time, “Friedan’s original idea for Aug. 26 was a national work stoppage, in which women would cease cooking and cleaning in order to draw attention to the unequal distribution of domestic labor, an issue she discussed in her 1963 bestseller The Feminine Mystique. It isn’t clear how many women truly went on ‘strike’ that day, but the march served as a powerful symbolic gesture. Participants held signs with slogans like ‘Don’t Iron While the Strike is Hot’ and ‘Don’t Cook Dinner – Starve a Rat Today.’”

CitePrintShareCohen, Sascha. “Women's Equality Day: The History of When Women Went on Strike.” Time, 26 August 2015, https://time.com/4008060/women-strike-equality-1970/.

Poster image from “Women's Strike for Equality.” Wikipedia, https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Women%27s_Strike_for_Equality.

Protests against the Vietnam War (1969-70)Protest against the Vietnam War, Texas, December, 1969. Credit: Jimmy Cochran.Antiwar march October 31, 1970, Seattle, two months after the death of Reuben Salazar in the Los Angeles Chicano Moratorium protestVietnam War Protests The Vietnam protest movement represented a growing anti-war movement in the United States in the late 1960s to early 1970s. Protestors spanned the racial spectrum and employed varying methods to end the war in Vietnam, started by the United States.

In many cases, anti-war protests combined with efforts to turn attention to domestic issues. As described in the Mapping American Social Movements Project of the University of Washington, “Chicanos in Los Angeles formed alliances with other oppressed people who identified with the Third World Left and were committed to toppling U.S. imperialism and fighting racism…. The Chicano Moratorium antiwar protests of 1970 and 1971…reflected the vibrant collaboration between African Americans, Japanese Americans, American Indians, and white antiwar activists that had developed in Southern California.”

CitePrintShareCochran, Jimmy W. “[Line of Protesters Against Vietnam War] - The Portal to Texas History.” The Portal to Texas History, https://texashistory.unt.edu/ark:/67531/metapth1276191/.

Estrada, Josue. Chicano Movement Geography - Mapping American Social Movements, https://depts.washington.edu/moves/Chicano_geography.shtml.

Disability Rights Movement Protest for the Rehabilitation Act (1973)Disability Rights Movement Protest for the Rehabilitation Act 1973, photographer Tom Olin Greyhound Bus Depot in Los Angeles, Diane Coleman, Steve Remington and Rick Wilson.The Civil Rights Movement for Black equality inspired many other movements, including a national push for disability rights. The Rehabilitation Act of 1973 prohibited discrimination on the basis of disability and protected equal access for people with disabilities in areas including public services, employment, and education.

CitePrintShare“History and Timeline | Department on Disability.” Department on Disability, https://disability.lacity.org/resources/celebrate-ada-30th-anniversary/history-and-timeline.

Protests for and against the Equal Rights Amendment (1973)Protests led by Phyllis Schlafly, center, opposed the passage of the Equal Rights Amendment, 1973.Women supporting the ERA carry a banner down Pennsylvania Avenue in Washington DC on August 26, 1977The Equal Rights Amendment (ERA) states: "Equality of rights under the law shall not be denied or abridged by the United States or by any state on account of sex." First proposed as an Amendment to the Constitution in 1923, Congress finally passed the ERA in 1972. The senate vote was overwhelming: 84 to 8. The Amendment then went to state legislatures for approval, requiring 38 for ratification. 22 states ratified in that first year, and 8 more in 1973. But then a grassroots opposition movement made significant inroads. 35 states eventually approved it by 1977, but the passage of the Amendment then stalled and the deadline expired in 1982.

In these photos, women who fought both for and against the Amendment’s passage are pictured protesting. In the top photograph, American attorney and conservative activist Phyllis Schlafly, founder of STOP-ERA, leads a protest against the Amendment. In the bottom photograph, women dressed in white – evoking suffragists of the past – protest in favor of the Amendment in Washington, DC on August 26, 1977 – the same date of the Women’s Strike seven years earlier (also included in this Spotlight Kit).

CitePrintShare“ERA wouldn't be good for women | Tuesday's letters.” Tampa Bay Times, 9 September 2019, https://www.tampabay.com/opinion/letters/2019/09/09/era-wouldnt-be-good-for-women-tuesdays-letters/.

Prasad, Ritu. “Women's Equal Rights Amendment sees first hearing in 36 years.” BBC, 30 April 2019, https://www.bbc.com/news/world-us-canada-44319712.

Boycott Lettuce & Grapes Poster (1978)Boycott Lettuce & Grapes (1978)Dolores Huerta Lettuce Boycott Poster: Dolores Huerta and Cesar Chavez fought together for the rights and protections of the workers who picked fruits and vegetables in the fields and orchards, organizing a workers’ union and boycotts to gain attention and create economic pressure for the cause. Huerta led a successful lettuce and grape boycott, first in California and later on a national scale, that paved the way for migrant labor protection laws.

CitePrintShare(1978) Boycott Lettuce & Grapes. United States, 1978. [Chicago: Women's Graphics Collective] [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/93505187/.

Lily Chin Holds a Photograph of Her Son Vincent Chin (1983)As explained by the New York Times, “Vincent Chin, a Chinese American man who lived near Detroit, was beaten to death with a baseball bat after being pursued by two white autoworkers in 1982…Mr. Chin was killed at a time when the rise of Japanese carmakers and the collapse of Detroit’s auto industry had contributed to a rise in anti-Asian racism.” The two men who murdered Chin accepted plea deals, serving only probation and paying about $3000 each in fines. In this image, Chin’s mother, Lily Chin, holds a photograph of her son.

CitePrintShareSmith, Mitch. “Decades After Infamous Beating Death, Recent Attacks Haunt Asian Americans.” The New York Times, 17 June 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/06/16/us/vincent-chin-anti-asian-attack-detroit.html.

Keith Haring, Ignorance = Fear / Silence = Death (1989)Keith Haring, Ignorance = Fear / Silence = Death (1989)In the earliest years of the emergency of AIDS as a public health crisis, the American Government’s response was limited in terms of both resources dedicated to fighting the disease and public discussion of the disease, its victims, and public health strategies for prevention. Activists coined the phrase “silence=death” in 1987 to help raise awareness and spur the government to devote greater resources and attention.

CitePrintShareSherwin, Skye. “Keith Haring’s Ignorance = Fear: political activism | Art and design.” The Guardian, 23 August 2019, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/aug/23/keith-haring-ignorance-equals-fear.

Tea Party Protests (2009)Tea Party protest at the Connecticut State Capitol in Hartford, Connecticut. April 15, 2009. Organizers reported that the police estimate of attendance was 5000 people.Protesters in Washington D.C. during a rally, September 2009.After the financial crisis of 2008, a CNBC commentator, Rick Santelli, argued against President Obama’s mortgage relief policies and evoked the Revolutionary War-era Tea Party in calling for a protest against them. The “Tea Party Movement” took hold among some conservative and libertarian circles, leading to rallies and political campaigns arguing against federal taxation and in favor of fiscal conservatism and a free market economy. Several rallies were held specifically on April 15th – Tax Day – 2009.

CitePrintShareRoss, Sage. “File:Tea Party Protest, Hartford, Connecticut, 15 April 2009 - 041.jpg.” Wikimedia Commons, https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Tea_Party_Protest,_Hartford,_Connecticut,_15_April_2009_-_041.jpg.

Zeleny, Jeff. “In Washington, Thousands Stage Protest of Big Government.” The New York Times, 12 September 2009, https://www.nytimes.com/2009/09/13/us/politics/13protestweb.html.

Occupy Wall Street / Park Avenue Millionaires Protest (2011)Occupy Wall Street Protests Starting in Washington, then moving to New York, protesters camped out in Zucotti park for an extended period of time in 2011 while voicing their concern about inequality in America. The protesters had a unique style of protesting employing methods such as “the people’s mic,” organized childcare, a library, and were predominantly “leaderless.” They had regularly scheduled marches throughout New York City for a variety of issues. Some critique focused on how participants were mostly white, accused of antisemitism, and had an amorphous set of demands.

CitePrintShareWires, N. P. R. S. and. (2011, October 15). Occupy Wall Street inspires worldwide protests. NPR. Retrieved February 27, 2022, from https://www.npr.org/2011/10/15/141382468/occupy-wall-street-inspires-worldwide-protests

Kastenbaum, Steve. “Occupy Wall Street: An experiment in consensus-building.” CNN, 18 October 2011, https://www.cnn.com/2011/10/18/us/occupy-wall-street-consensus-building/index.html.

Rally in Support of DACA (2017)In September of 2017, Attorney General Jeff Sessions’ announcement that the Trump Administration planned to end DACA, or the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals program, was met with protests around the country. As reported by National Public Radio, “hundreds of demonstrators gathered outside the White House. They shouted ‘We are America’ and ‘We want education. Down with deportation.’ The marchers then proceeded to the Department of Justice…and to the Trump International Hotel on Pennsylvania Avenue, where they staged a sit-in.”

CitePrintShareNeuman, Scott. “Protesters In D.C., Denver, LA, Elsewhere Demonstrate Against Rescinding DACA.” NPR, 5 September 2017, https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/09/05/548727220/protests-in-d-c-denver-la-elsewhere-protest-rescinding-daca.

Dakota Access Pipeline Protest (2017)Dakota Access Pipeline Protests (2017)The planned construction of The Dakota Access Pipeline and resulting protests is a recent example of Native Americans and U.S. industry clashing. One side feared for the quality of their water and lands being abused. Proponents of the pipeline included union members and business, who viewed the pipeline’s development as essential to the growth of the economy.

CitePrintShareHersher, R. (2017, February 22). Key moments in the Dakota Access Pipeline Fight. NPR. Retrieved February 27, 2022, from https://www.npr.org/sections/thetwo-way/2017/02/22/514988040/key-moments-in-the-dakota-access-pipeline-fight

Iowa Public Radio | By Amy Mayer. (2020, August 28). Public Voices Support and oppose Bakken pipeline across Iowa. Iowa Public Radio. Retrieved February 26, 2022, from https://www.iowapublicradio.org/environment/2015-11-12/public-voices-support-and-oppose-bakken-pipeline-across-iowa#stream/0

How do you sign ‘Black Lives Matter’ in ASL? (2020)How do you sign ‘Black Lives Matter’ in ASL? (2020)As reported by the Los Angeles Times, the intersection of disability rights and racial equity can be complicated for deaf members of the Black Lives Matter Movement: “The phrase begins with four fingers cut across the brow, followed by two thumbs drawn up like breath from navel to chest, ending with a fierce tug with two hands down from the chin into fists toward the heart.

Black. Life. Cherish. This is how Harold Foxx and many other black deaf Angelenos sign ‘Black Lives Matter,’ though it is by no means a universal translation. .. It is a reminder of an ongoing struggle for equity, representation and authenticity in ASL, a language deeply scarred by racism and exclusion.”

CitePrintShareSharp, Sonja. “Column One: How do you sign 'Black Lives Matter' in ASL? For black deaf Angelenos, it's complicated.” Los Angeles Times, 8 June 2020, https://www.latimes.com/california/story/2020-06-08/how-do-you-sign-black-lives-matter-in-asl-for-black-deaf-angelenos-its-complicated.

Black Lives Matter Plaza (2020)Black Lives Matter Plaza (2020)On June 5, 2020, CNN reported: “Washington, DC is painting a message in giant, yellow letters down a busy DC street ahead of a planned protest this weekend: BLACK LIVES MATTER.

The massive banner-like project spans two blocks of 16th Street, a central axis that leads southward straight to the White House. Each of the 16 bold yellow letters spans the width of the two-lane street, creating an unmistakable visual easily spotted by aerial cameras and virtually anyone within a few blocks. The painters were contacted by Mayor Muriel Bowser and began work early Friday morning, the mayor’s office told CNN. Bowser has officially deemed the section of 16th Street bearing the mural ‘Black Lives Matter Plaza,’ complete with a new street sign.”

CitePrintShareSource of text: Willingham, AJ. “Washington, DC paints a giant 'Black Lives Matter' message on the road to the White House.” CNN, 5 June 2020, https://www.cnn.com/2020/06/05/us/black-lives-matter-dc-street-white-house-trnd/index.html.

Source of photo: “DC paints huge Black Lives Matter mural near White House.” WCTV, 5 June 2020, https://www.kktv.com/content/news/DC-paints-huge-Black-Lives-Matter-mural-near-White-House-571049311.html.

Protests against Mask Mandates (2021)People demonstrate against mask mandates at a Cobb county, Georgia, school board meeting last week. Photograph: Robin Rayne/Zuma Press Wire/Rex/Shutterstock (2021)Families protest any potential mask mandates before the Hillsborough County School Board meeting last month in Tampa, Fla.During the height of the Coronavirus pandemic, all levels of government – federal, state, and local – were required to respond to information emerging daily about what policies and practices would be safest for the public. In many places, including public spaces and schools, people were required to wear masks. Some people pushed back against these requirements, arguing that mandates were a violation of their individual rights.

CitePrintShareWong, Julia Carrie. “Masks off: how US school boards became 'perfect battlegrounds' for vicious culture wars.” The Guardian, 24 August 2021, https://www.theguardian.com/us-news/2021/aug/24/mask-mandates-covid-school-boards.

Shivaram, Deepa. “'Mask Wars' Are Erupting In Schools As Students Return : Back To School: Live Updates.” NPR, 20 August 2021, https://www.npr.org/sections/back-to-school-live-updates/2021/08/20/1028841279/mask-mandates-school-protests-teachers.

Rally against CRT in Schools (2021)Capitol rally to “stop critical race theory in Pennsylvania schools.” Harrisburg, Pennsylvania, July 14, 2021. Dan GleiterWhile “Critical Race Theory” (CRT) is taught primarily in law schools, protests began in 2021 against the teaching of CRT at local school board meetings in many places across the country. Often, participants in these protests raised a range of concerns about how topics including, but not limited to, race are covered in school curricula. These protests became part of a larger “parents’ rights” movement, arguing that parents should have a greater say in determining what their children learn in school.

CitePrintShareDeJesus, Ivey. “Critical race theory: What it is, what it isn't, and what it means for education in Pennsylvania.” Penn Live, 15 July 2021, https://www.pennlive.com/news/2021/07/critical-race-theory-the-nationwide-debate-is-emerging-in-pennsylvania.html.

“I Still Believe in Our City” Public Art (2021)The “I Still Believe In Our City” public art series was created in partnership with the New York City Commission on Human Rights. Courtesy Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya"I Am Not Your Scapegoat" poster.Courtesy Amanda PhingbodhipakkiyaAs reported by NBC News, “Last winter, as violent attacks against Asian elders began to spike, vividly painted portraits of Asian, Pacific Islander and Black people — flanked by vibrant florals and messages like ‘I am not your scapegoat’ — appeared on the walls of New York City's busiest subway and bus stops. Amanda Phingbodhipakkiya’s I Still Believe In Our City public art series, created in partnership with the New York City Commission on Human Rights, reminded millions of commuters of the humanity, diversity and beauty of Asian Americans at a time when many saw them as mere carriers of a deadly virus.”

CitePrintShareWang, Claire. “'I am not your scapegoat': See the art created by Asian Americans in a year of anti-Asian hate.” NBC News, 27 December 2021, https://www.nbcnews.com/news/asian-america/-not-scapegoat-see-art-created-asian-americans-year-anti-asian-hate-rcna9058.

March against Florida House Bill 1557 (2022)Demonstrators headed toward a pier in St. Petersburg during a rally against the bill.As reported by the New York Times in March of 2022, Gov. Ron DeSantis of Florida signed House Bill 1557, “which supporters call the ‘Parental Rights in Education’ bill, but that opponents refer to as the ‘Don’t Say Gay’ bill.” Among the provisions of the bill, “Instruction on gender and sexuality would be constrained in all grades; schools would be required to notify parents when children receive mental, emotional or physical health services, unless educators believe there is a risk of ‘abuse, abandonment, or neglect’; and parents would have the right to opt their children out of counseling and health services.”

CitePrintShareGoldstein, Dana. “What’s in House Bill 1557, Which Opponents Call ‘Don’t Say Gay.’” The New York Times, 18 March 2022, https://www.nytimes.com/2022/03/18/us/dont-say-gay-bill-florida.html.

Education for American Democracy

In this lesson, students are presented with a series of searches/seizures and they are asked to evaluate whether they are lawful or not.

The Roadmap

American Bar Association

This lesson plan will help students grasp the goals of the federal government as stated in the preamble to the constitution through small group exercises and concluding with a presentation to their classmates.

The Roadmap

Emerging America - Collaborative for Educational Services

The lesson explores the philosophical argument for equal and inalienable rights and their implications for government.

The Roadmap

Bill of Rights Institute

In the summer of 1787, delegates gathered for a convention in Philadelphia, with the goal of revising the Articles of Confederation—the nation’s existing governing document, which wasn’t really working. Instead, they wrote a whole new document, which created a revolutionary form of government: the U.S. Constitution.

The Roadmap

National Constitution Center

Download the Roadmap and Report

Download the Educating for American Democracy Roadmap and Report Documents

Get the Roadmap and Report to unlock the work of over 300 leading scholars, educators, practitioners, and others who spent thousands of hours preparing this robust framework and guiding principles. The time is now to prioritize history and civics.

Your contact information will not be shared, and only used to send additional updates and materials from Educating for American Democracy, from which you can unsubscribe.

We the People

This theme explores the idea of “the people” as a political concept–not just a group of people who share a landscape but a group of people who share political ideals and institutions.

Institutional & Social Transformation

This theme explores how social arrangements and conflicts have combined with political institutions to shape American life from the earliest colonial period to the present, investigates which moments of change have most defined the country, and builds understanding of how American political institutions and society changes.

Contemporary Debates & Possibilities

This theme explores the contemporary terrain of civic participation and civic agency, investigating how historical narratives shape current political arguments, how values and information shape policy arguments, and how the American people continues to renew or remake itself in pursuit of fulfillment of the promise of constitutional democracy.

Civic Participation

This theme explores the relationship between self-government and civic participation, drawing on the discipline of history to explore how citizens’ active engagement has mattered for American society and on the discipline of civics to explore the principles, values, habits, and skills that support productive engagement in a healthy, resilient constitutional democracy. This theme focuses attention on the overarching goal of engaging young people as civic participants and preparing them to assume that role successfully.

Our Changing landscapes

This theme begins from the recognition that American civic experience is tied to a particular place, and explores the history of how the United States has come to develop the physical and geographical shape it has, the complex experiences of harm and benefit which that history has delivered to different portions of the American population, and the civics questions of how political communities form in the first place, become connected to specific places, and develop membership rules. The theme also takes up the question of our contemporary responsibility to the natural world.

A New Government & Constitution

This theme explores the institutional history of the United States as well as the theoretical underpinnings of constitutional design.

A People in the World

This theme explores the place of the U.S. and the American people in a global context, investigating key historical events in international affairs,and building understanding of the principles, values, and laws at stake in debates about America’s role in the world.

The Seven Themes

The Seven Themes provide the organizational framework for the Roadmap. They map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. Importantly, they are neither standards nor curriculum, but rather a starting point for the design of standards, curricula, resources, and lessons.

Driving questions provide a glimpse into the types of inquiries that teachers can write and develop in support of in-depth civic learning. Think of them as a starting point in your curricular design.

Learn more about inquiry-based learning in the Pedagogy Companion.

Sample guiding questions are designed to foster classroom discussion, and can be starting points for one or multiple lessons. It is important to note that the sample guiding questions provided in the Roadmap are NOT an exhaustive list of questions. There are many other great topics and questions that can be explored.

Learn more about inquiry-based learning in the Pedagogy Companion.

The Seven Themes

The Seven Themes provide the organizational framework for the Roadmap. They map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. Importantly, they are neither standards nor curriculum, but rather a starting point for the design of standards, curricula, resources, and lessons.

The Five Design Challenges

America’s constitutional politics are rife with tensions and complexities. Our Design Challenges, which are arranged alongside our Themes, identify and clarify the most significant tensions that writers of standards, curricula, texts, lessons, and assessments will grapple with. In proactively recognizing and acknowledging these challenges, educators will help students better understand the complicated issues that arise in American history and civics.

Motivating Agency, Sustaining the Republic

- How can we help students understand the full context for their roles as civic participants without creating paralysis or a sense of the insignificance of their own agency in relation to the magnitude of our society, the globe, and shared challenges?

- How can we help students become engaged citizens who also sustain civil disagreement, civic friendship, and thus American constitutional democracy?

- How can we help students pursue civic action that is authentic, responsible, and informed?

America’s Plural Yet Shared Story

- How can we integrate the perspectives of Americans from all different backgrounds when narrating a history of the U.S. and explicating the content of the philosophical foundations of American constitutional democracy?

- How can we do so consistently across all historical periods and conceptual content?

- How can this more plural and more complete story of our history and foundations also be a common story, the shared inheritance of all Americans?

Simultaneously Celebrating & Critiquing Compromise

- How do we simultaneously teach the value and the danger of compromise for a free, diverse, and self-governing people?

- How do we help students make sense of the paradox that Americans continuously disagree about the ideal shape of self-government but also agree to preserve shared institutions?

Civic Honesty, Reflective Patriotism

- How can we offer an account of U.S. constitutional democracy that is simultaneously honest about the wrongs of the past without falling into cynicism, and appreciative of the founding of the United States without tipping into adulation?

Balancing the Concrete & the Abstract

- How can we support instructors in helping students move between concrete, narrative, and chronological learning and thematic and abstract or conceptual learning?

Each theme is supported by key concepts that map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. They are vertically spiraled and developed to apply to K—5 and 6—12. Importantly, they are not standards, but rather offer a vision for the integration of history and civics throughout grades K—12.

Helping Students Participate

- How can I learn to understand my role as a citizen even if I’m not old enough to take part in government? How can I get excited to solve challenges that seem too big to fix?

- How can I learn how to work together with people whose opinions are different from my own?

- How can I be inspired to want to take civic actions on my own?

America’s Shared Story

- How can I learn about the role of my culture and other cultures in American history?

- How can I see that America’s story is shared by all?

Thinking About Compromise

- How can teachers teach the good and bad sides of compromise?

- How can I make sense of Americans who believe in one government but disagree about what it should do?

Honest Patriotism

- How can I learn an honest story about America that admits failure and celebrates praise?

Balancing Time & Theme

- How can teachers help me connect historical events over time and themes?

The Six Pedagogical Principles

EAD teacher draws on six pedagogical principles that are connected sequentially.

Six Core Pedagogical Principles are part of our Pedagogy Companion. The Pedagogical Principles are designed to focus educators’ effort on techniques that best support the learning and development of student agency required of history and civic education.

EAD teachers commit to learn about and teach full and multifaceted historical and civic narratives. They appreciate student diversity and assume all students’ capacity for learning complex and rigorous content. EAD teachers focus on inclusion and equity in both content and approach as they spiral instruction across grade bands, increasing complexity and depth about relevant history and contemporary issues.

Growth Mindset and Capacity Building

EAD teachers have a growth mindset for themselves and their students, meaning that they engage in continuous self-reflection and cultivate self-knowledge. They learn and adopt content as well as practices that help all learners of diverse backgrounds reach excellence. EAD teachers need continuous and rigorous professional development (PD) and access to professional learning communities (PLCs) that offer peer support and mentoring opportunities, especially about content, pedagogical approaches, and instruction-embedded assessments.

Building an EAD-Ready Classroom and School

EAD teachers cultivate and sustain a learning environment by partnering with administrators, students, and families to conduct deep inquiry about the multifaceted stories of American constitutional democracy. They set expectations that all students know they belong and contribute to the classroom community. Students establish ownership and responsibility for their learning through mutual respect and an inclusive culture that enables students to engage courageously in rigorous discussion.

Inquiry as the Primary Mode for Learning

EAD teachers not only use the EAD Roadmap inquiry prompts as entry points to teaching full and complex content, but also cultivate students’ capacity to develop their own deep and critical inquiries about American history, civic life, and their identities and communities. They embrace these rigorous inquiries as a way to advance students’ historical and civic knowledge, and to connect that knowledge to themselves and their communities. They also help students cultivate empathy across differences and inquisitiveness to ask difficult questions, which are core to historical understanding and constructive civic participation.

Practice of Constitutional Democracy and Student Agency

EAD teachers use their content knowledge and classroom leadership to model our constitutional principle of “We the People” through democratic practices and promoting civic responsibilities, civil rights, and civic friendship in their classrooms. EAD teachers deepen students’ grasp of content and concepts by creating student opportunities to engage with real-world events and problem-solving about issues in their communities by taking informed action to create a more perfect union.

Assess, Reflect, and Improve

EAD teachers use assessments as a tool to ensure all students understand civics content and concepts and apply civics skills and agency. Students have the opportunity to reflect on their learning and give feedback to their teachers in higher-order thinking exercises that enhance as well as measure learning. EAD teachers analyze and utilize feedback and assessment for self-reflection and improving instruction.

EAD teachers commit to learn about and teach full and multifaceted historical and civic narratives. They appreciate student diversity and assume all students’ capacity for learning complex and rigorous content. EAD teachers focus on inclusion and equity in both content and approach as they spiral instruction across grade bands, increasing complexity and depth about relevant history and contemporary issues.

Growth Mindset and Capacity Building

EAD teachers have a growth mindset for themselves and their students, meaning that they engage in continuous self-reflection and cultivate self-knowledge. They learn and adopt content as well as practices that help all learners of diverse backgrounds reach excellence. EAD teachers need continuous and rigorous professional development (PD) and access to professional learning communities (PLCs) that offer peer support and mentoring opportunities, especially about content, pedagogical approaches, and instruction-embedded assessments.

Building an EAD-Ready Classroom and School

EAD teachers cultivate and sustain a learning environment by partnering with administrators, students, and families to conduct deep inquiry about the multifaceted stories of American constitutional democracy. They set expectations that all students know they belong and contribute to the classroom community. Students establish ownership and responsibility for their learning through mutual respect and an inclusive culture that enables students to engage courageously in rigorous discussion.

Inquiry as the Primary Mode for Learning

EAD teachers not only use the EAD Roadmap inquiry prompts as entry points to teaching full and complex content, but also cultivate students’ capacity to develop their own deep and critical inquiries about American history, civic life, and their identities and communities. They embrace these rigorous inquiries as a way to advance students’ historical and civic knowledge, and to connect that knowledge to themselves and their communities. They also help students cultivate empathy across differences and inquisitiveness to ask difficult questions, which are core to historical understanding and constructive civic participation.

Practice of Constitutional Democracy and Student Agency

EAD teachers use their content knowledge and classroom leadership to model our constitutional principle of “We the People” through democratic practices and promoting civic responsibilities, civil rights, and civic friendship in their classrooms. EAD teachers deepen students’ grasp of content and concepts by creating student opportunities to engage with real-world events and problem-solving about issues in their communities by taking informed action to create a more perfect union.

Assess, Reflect, and Improve

EAD teachers use assessments as a tool to ensure all students understand civics content and concepts and apply civics skills and agency. Students have the opportunity to reflect on their learning and give feedback to their teachers in higher-order thinking exercises that enhance as well as measure learning. EAD teachers analyze and utilize feedback and assessment for self-reflection and improving instruction.