The curated resources linked below are an initial sample of the resources coming from a collaborative and rigorous review process with the EAD Content Curation Task Force.

Reset All

Reset All

The phrase “a house divided” comes from Abraham Lincoln’s speech to the Illinois Republican State Convention in 1858, when he describes a nation so badly torn between those that permitted slavery and those that prohibited it that it was on the brink of war. While the issue of slavery is understood to be central to the start of the Civil War, this set of resources is intended to introduce students to more details of the growing tension in the nation. Resources include information and images about expanding territory and the addition of new states to the union; voices of the abolitionist movement; political tension and acts of violence. It does not provide comprehensive coverage of these decades, but it helps to highlight that the growing tension was both multifaceted and happening across the entire nation.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by Decade1830s (4)1840s (3)1850s (9)

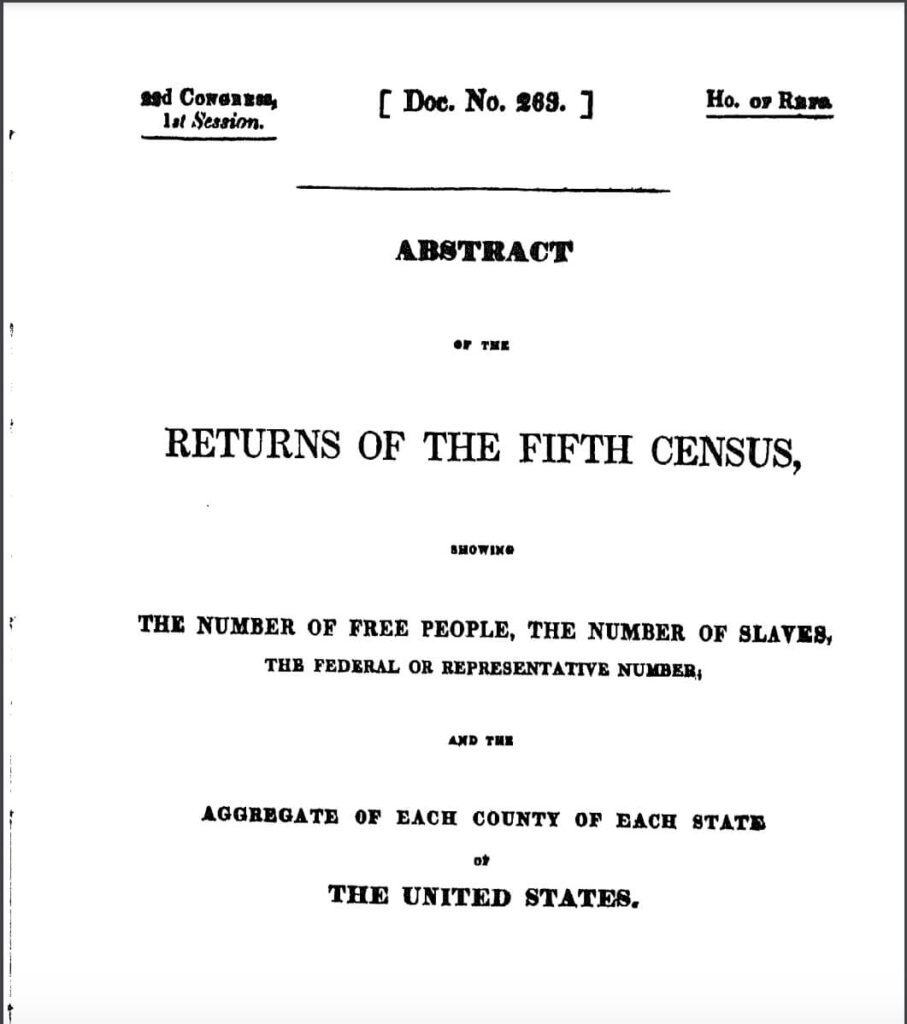

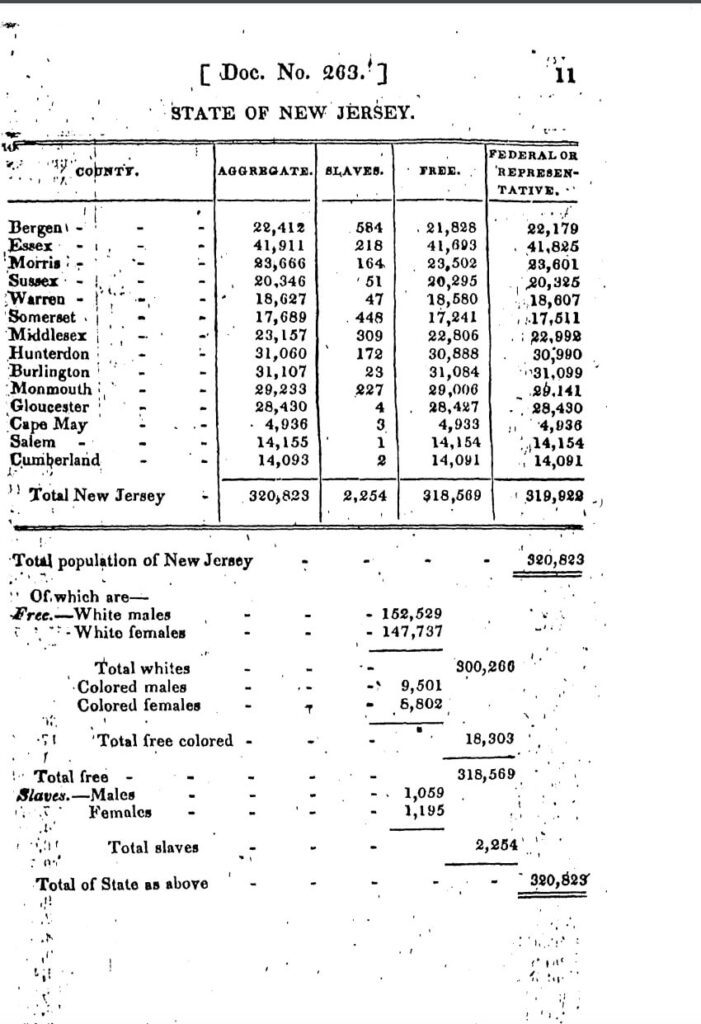

- All 16 Primary ResourcesThe Census of 1830

This abstract of the Census from 1830 not only provides numbers, state by state, of free and enslaved persons – but students will note that there are enslaved persons in many of the states they consider “free” (sample pages at left).

Note that the terminology is historically accurate but might be offensive to students unless context is provided (this will be true for many of the documents from this era).

CitePrintSharehttps://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1830/1830b.pdf

ORIIN, DUFF. “1830 Census - Full Document.” Census.gov, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1830/1830b.pdf.

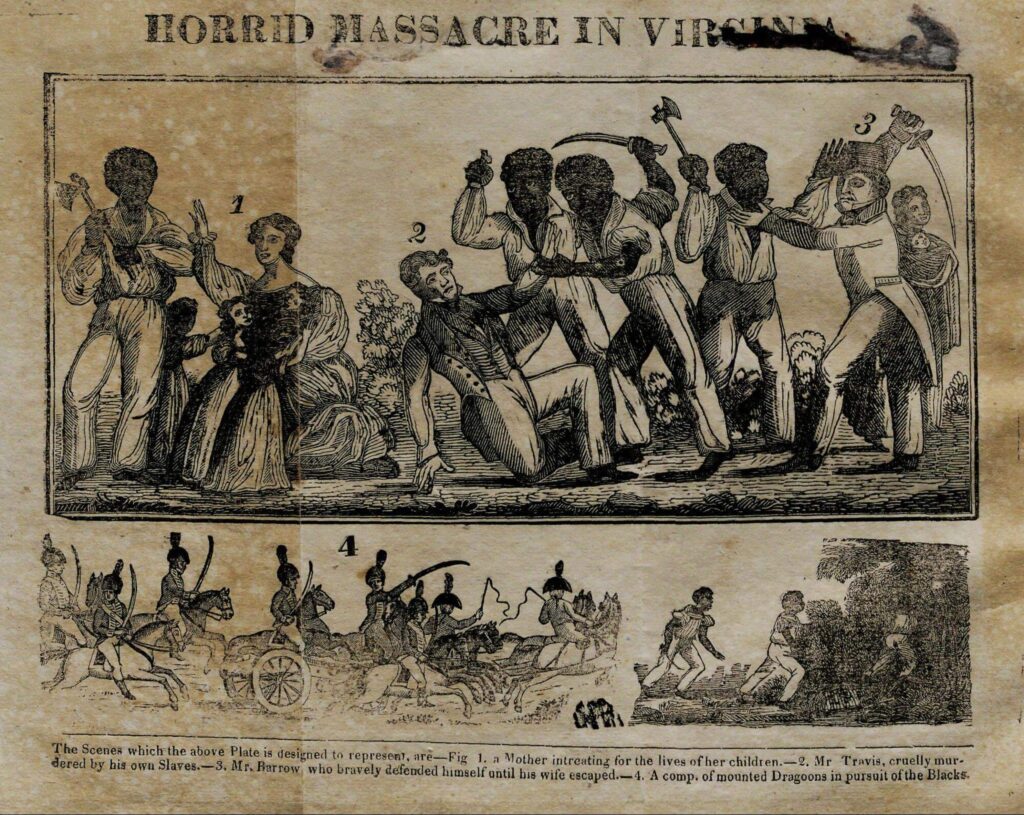

Nat Turner’s Rebellion, 1831Transcript“Even though Turner and his followers had been stopped, panic spread across the region. In the days following the attack, 3000 soldiers, militia men, and vigilantes killed more than one hundred suspected rebels. …Nat Turner’s rebellion led to the passage of a series of new laws. The Virginia legislature actually debated ending slavery, but chose instead to impose additional restrictions and harsher penalties on the activities of both enslaved and free African Americans. Other slave states followed suit, restricting the rights of free and enslaved blacks to gather in groups, travel, preach, and learn to read and write.” (Gilder Lehrman, link at right.)

Nat Turner’s Rebellion led to both public debate and a tightening of laws and policies. “Nat Turner was an enslaved man who had learned to read and write and become a religious leader despite his enslavement; following what he took to be religious signs, he led other enslaved people in an armed uprising. The violence of the uprising and Turner’s ability to escape and hide for approximately six weeks following the event led to changes in laws and policies and also led to a widespread climate of fear among white slaveholders. Enslaved people in far-flung states who had no connection to the event were lynched by white mobs. The State of Virginia briefly considered ending the practice of slavery in the wake of the rebellion, but they ultimately decided instead to tighten the laws of slavery.

1Africans in America/Part 3/Nat Turner's Rebellion. (n.d.). PBS. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part3/3p1518.html and Nat Turner - Rebellion, Death & Facts - HISTORY. (2021, January 26). History.com. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/nat-turnerCitePrintShareAllyn, Nelson. “Nat Turner's Rebellion, 1831 | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History |, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/nat-turner%E2%80%99s-rebellion-1831.

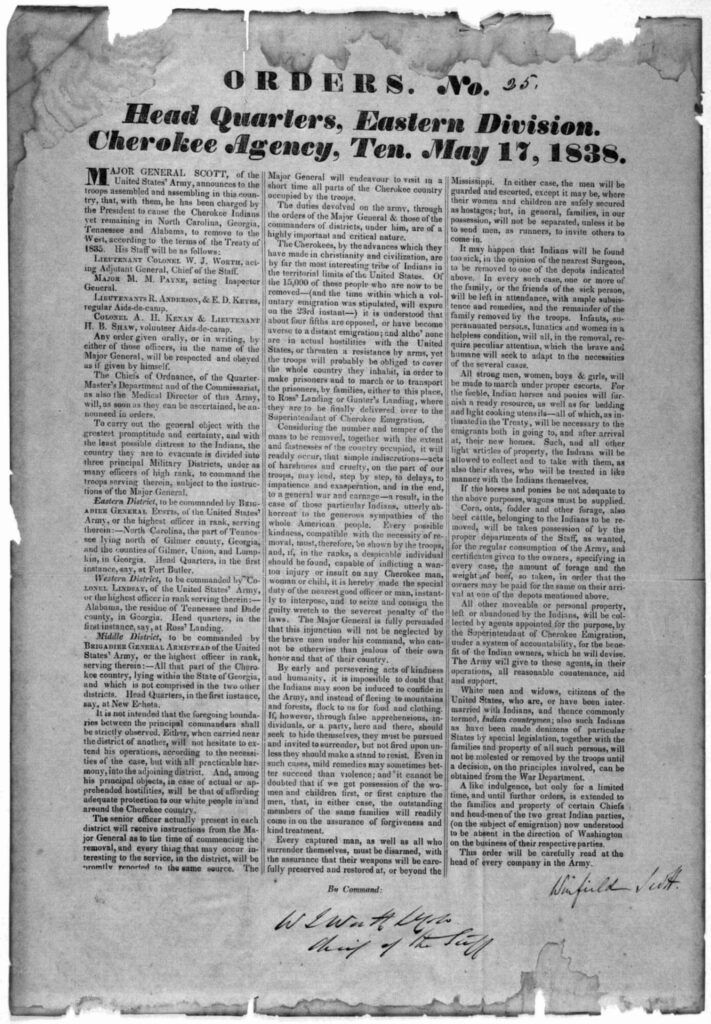

Orders pursuant to the Indian Removal Act of 1830 (Trail of Tears)Orders pursuant to the Indian Removal Act of 1830 (Trail of Tears)While the Trail of Tears and “Indian Removal Act” are not central to understanding slavery, they are critical events in the history of the country in this era; in addition, the concept of “indian removal” connects directly to tensions that rose as the nation expanded in both population and territory.

As the United States acquired Western territories, and as the power battle between slaveholding and free states continued, the land on which Native nations lived became increasingly valuable. After President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Choctaw, Creek, and Cherokee nations were forced to move from their land, most often on foot and with the deaths of many people, into Western territories. The 1838 forced removal of the Cherokee people from their Georgia land led to the deaths of thousands of people (exact numbers are unknown, but estimates range around 4,000 - 5,000.)

1- History & Culture - Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail (US National Park Service). (2020, July 10). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/trte/learn/historyculture/index.htm and Trail of Tears: Indian Removal Act, Facts & Significance - HISTORY. (2020, July 7). History.com. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/trail-of-tears

CitePrintShare“Tile.loc.gov.” Library of Congress, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/rbc/rbpe/rbpe17/rbpe174/1740400a/1740400a.pdf.

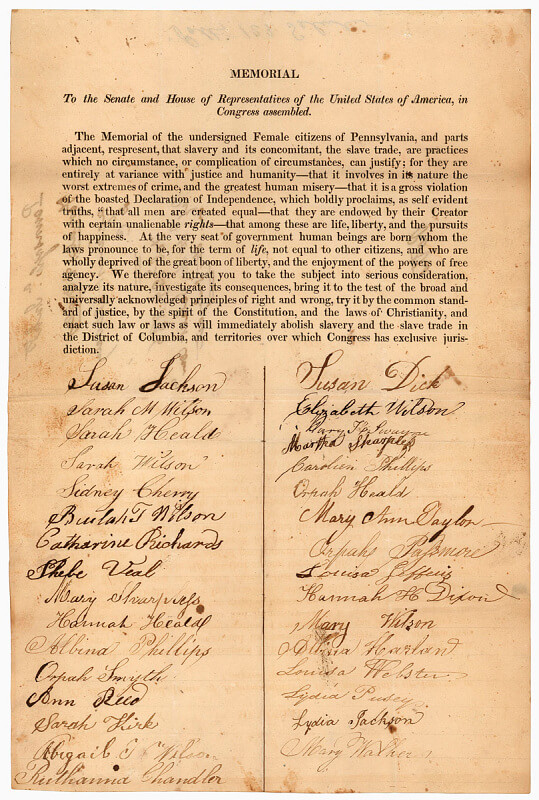

The Gag Rule, 1836“On May 26, 1836, the House of Representatives adopted a ‘Gag Rule’ stating that all petitions regarding slavery would be tabled without being read, referred, or printed….The enactment of the Gag Rule, rather than discouraging petitioners, energized the anti-slavery movement to flood the Capitol with written demands. Activists held up the suppression of debate as an example of the slaveholding South’s infringement of the rights of all Americans.”

CitePrintShareAdams, John Quincy. “The Gag Rule | National Museum of American History.” National Museum of American History, https://americanhistory.si.edu/democracy-exhibition/beyond-ballot/petitioning/gag-rule.

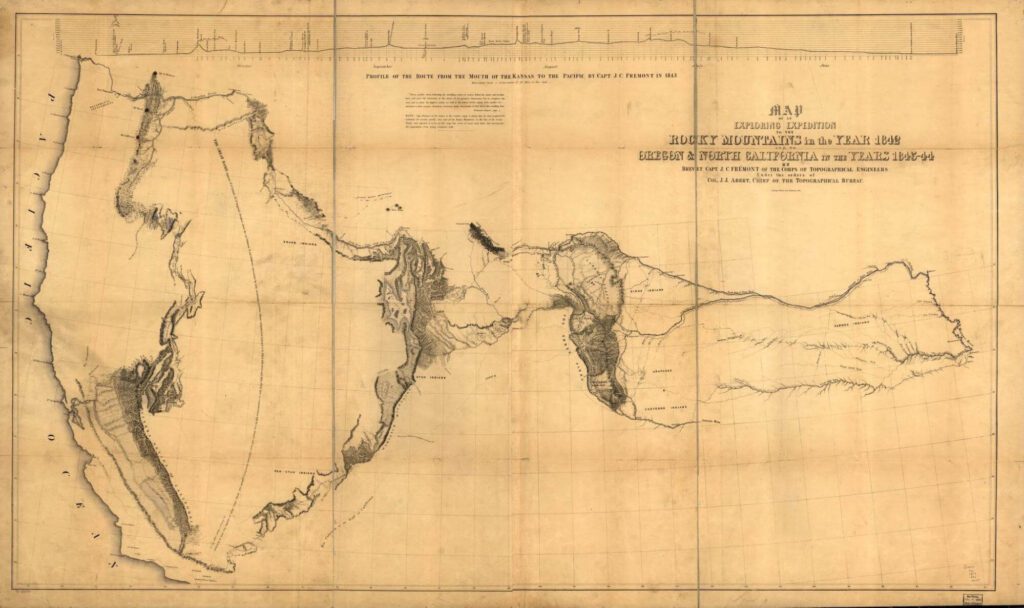

Map of Westward Expedition and Expansion, 1842-44Map of an exploring expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the year 1842 and to Oregon & north California in the years 1843-44As the nation expanded Westward, tensions rose further over whether new states and territories would permit or prohibit slavery.

CitePrintShareMap of an Exploring Expedition to the Rocky ... - Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4051s.ct000909/.

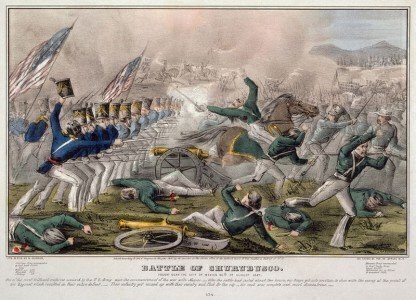

Battlefield Painting, Mexican-American WarBattlefield Painting, Mexican-American War“The pact set a border between Texas and Mexico and ceded California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming to the United States. …the acquisition of so much territory with the issue of slavery unresolved lit the fuse that eventually set off the Civil War in 1861.”

CitePrintShare“The Mexican-American war in a nutshell.” National Constitution Center, 13 May 2021, https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/the-mexican-american-war-in-a-nutshell.

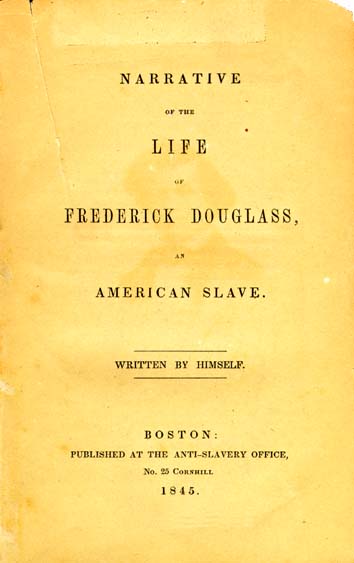

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, excerpt, 1845TranscriptCHAPTER I. I WAS born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about twelve miles from Easton, in Talbot county, Maryland. I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it. By far the larger part of the slaves know as little of their ages as horses know of theirs, and it is the wish of most masters within my knowledge to keep their slaves thus ignorant. I do not remember to have ever met a slave who could tell of his birthday. They seldom come nearer to it than planting-time, harvest-time, cherry-time, spring-time, or fall-time. A want of information concerning my own was a source of unhappiness to me even during childhood. The white children could tell their ages. I could not tell why I ought to be deprived of the same privilege. I was not allowed to make any inquiries of my master concerning it. He deemed all such inquiries on the part of a slave improper and impertinent, and evidence of a restless spirit. The nearest estimate I can give makes me now between twenty-seven and twenty-eight years of age. I come to this, from hearing my master say, some time during 1835, I was about seventeen years old.

Students would benefit from reading an excerpt of the text of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass – but in addition, the cover itself is an interesting artifact, and students can discuss its details and its possible impact upon publication in 1845. (See also text in this chart, below, from Frederick Douglass’ July 4 address in 1852.)

CitePrintShareHempel, Carlene, et al. “Frederick Douglass, 1818-1895. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself.” Documenting the American South, https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/douglass/douglass.html.

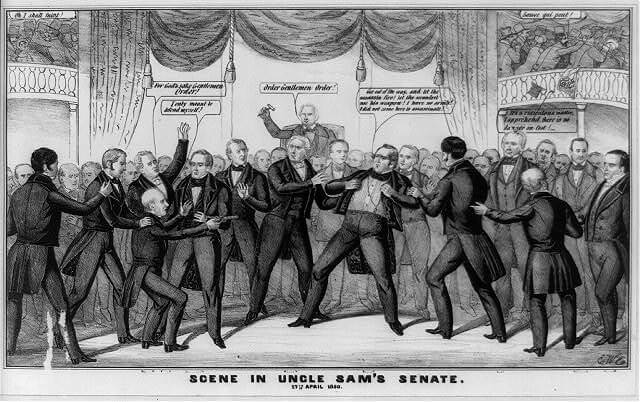

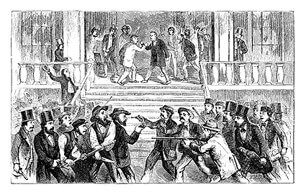

Scene in Uncle Sam’s Senate, 1850“Scene in Uncle Sam's Senate.Transcript"A somewhat tongue-in-cheek dramatization of the moment during the heated debate in the Senate over the admission of California as a free state when Mississippi senator Henry S. Foote drew a pistol on Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri.”

As new states were added to the nation, the question of how many would permit slavery and how many would prohibit it – and, therefore, which faction had more power – continued to contribute to growing tension.

CitePrintShare“Scene in Uncle Sam's Senate. 17th April 1850.” The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2008661528/.

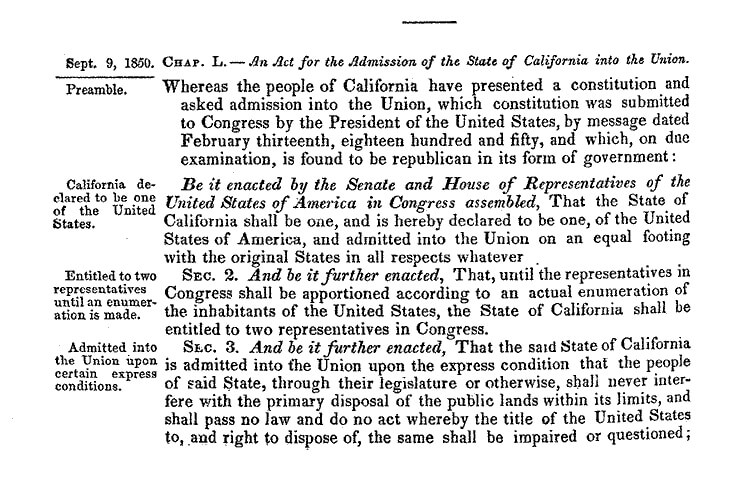

An Act for the Admission of the State of California into the Union, 1850CitePrintShareA Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875, https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=009%2Fllsl009.db&recNum=479.

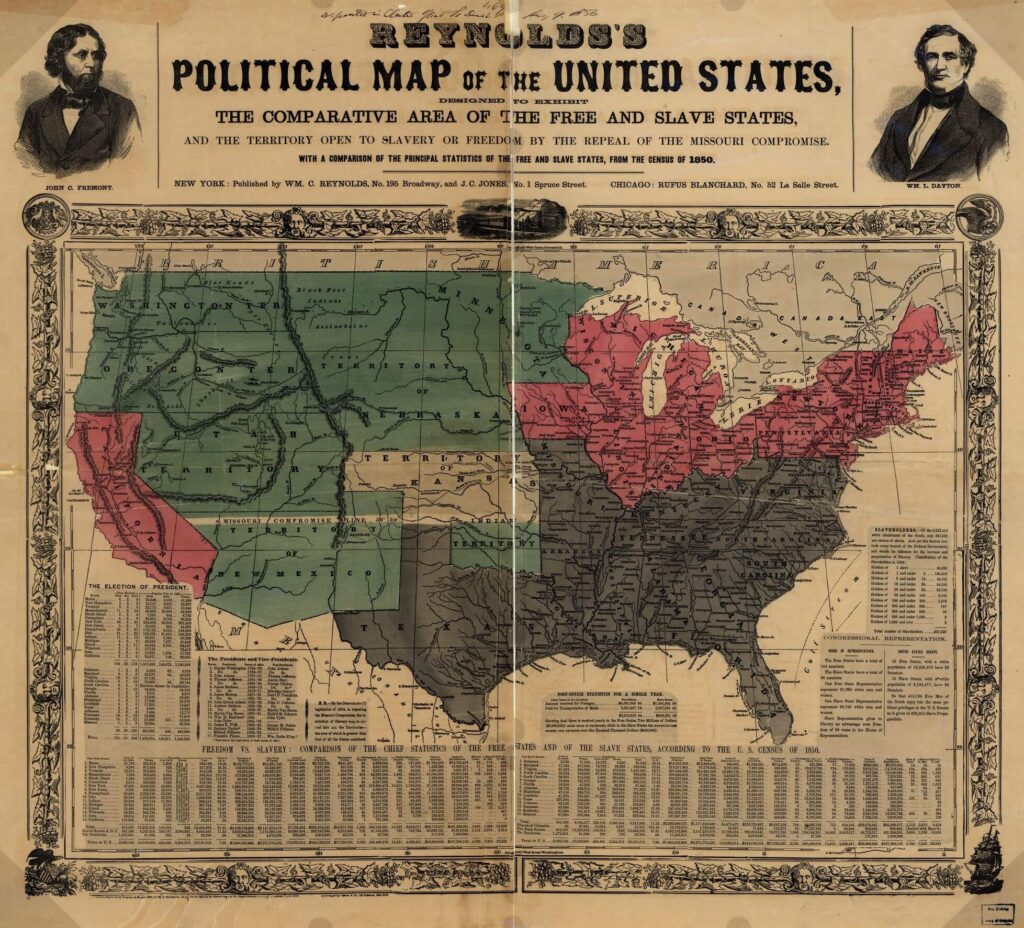

Political Map of the United States in 1850Political map of the United States in 1850This map has a range of valuable information, not only about Presidential politics, but also about population statistics and slavery. It makes a particular point of comparison with the 1830 Census, hyperlinked above in this chart.

CitePrintShare“1850 Political Map of the United States - History.” U.S. Census Bureau, 9 December 2021, https://www.census.gov/history/www/reference/maps/1850_political_map_of_the_united_states.html.

Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”, 1852Douglass raises critical questions about patriotism, citizenship, and the nation’s ideals in this address. The text highlights issues that will continue to be points of tension not only at the start of the Civil War, but throughout Reconstruction (and, truly, throughout American history).

“I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us. I am not included within the pale of glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

- Frederick Douglass, July 5, 1852CitePrintShareJuly 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass keynote address at an Independence Day celebration: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

“A Nation's Story: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”” National Museum of African American History and Culture, 3 July 2018, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/nations-story-what-slave-fourth-july.

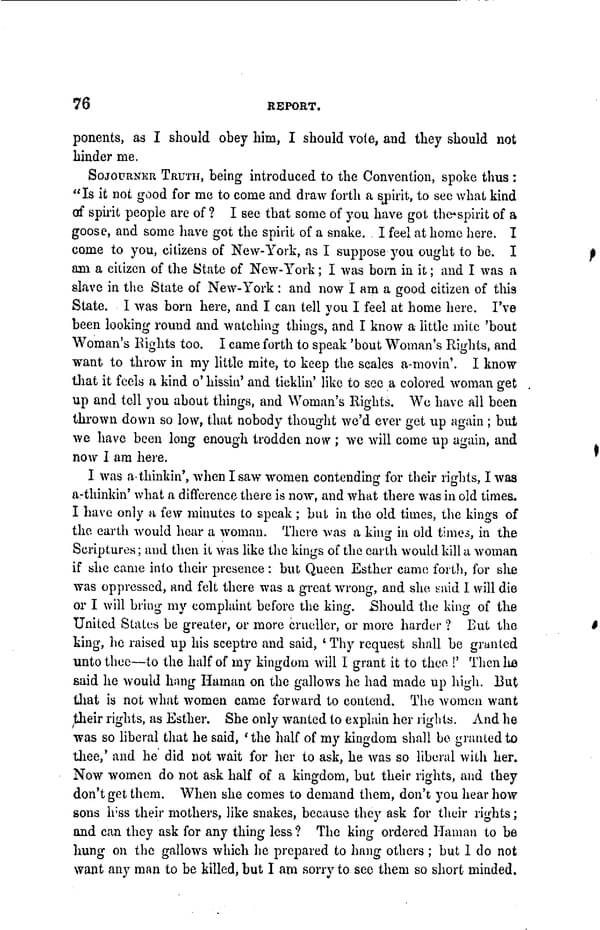

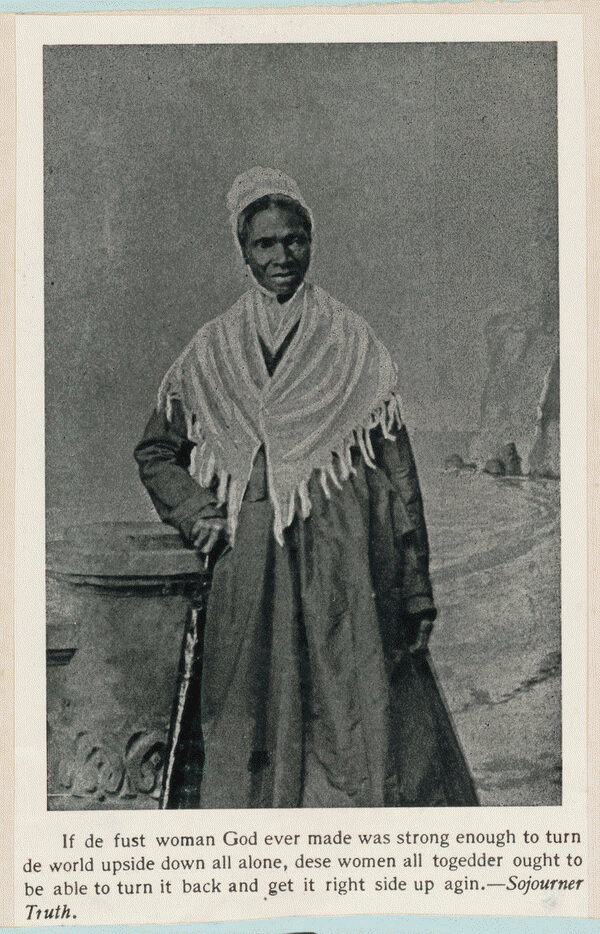

Sojourner Truth, Photograph and Speech at the Women’s Rights Convention, 1853See above; understanding the life and words of Sojourner Truth helps students to understand the complexity and intersectionality of both the women’s rights movement and the abolitionist movement.

CitePrintShareTitle Proceedings of the Woman's Rights Convention held at the Broadway Tabernacle, in the city of New York, on Tuesday and Wednesday, Sept. 6th and 7th, 1853.

Summary Sojourner Truth addresses the convention.

Image 76 of Susan B. Anthony Collection Copy | Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbnawsa.n8289/?sp=76.

“Bleeding Kansas,” 1858“The years of 1854-1861 were a turbulent time in Kansas territory. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 …allowed the residents of these territories to decide by popular vote whether their state would be free or slave. This concept of self-determination was called popular sovereignty'. …Three distinct political groups occupied Kansas: pro-slavers, free-staters and abolitionists. Violence broke out immediately between these opposing factions and continued until 1861 when Kansas entered the Union as a free state on January 29th. This era became forever known as ‘Bleeding Kansas’.” (National Park Service, link at right.)

CitePrintShare“Bleeding Kansas - Fort Scott National Historic Site (US National Park Service).” National Park Service, 23 April 2020, https://www.nps.gov/fosc/learn/historyculture/bleeding.htm.

Abraham Lincoln, “A House Divided” Speech, 1858This excerpt from (or the entirety of) Lincoln’s address to the Republican State Convention puts the notion of “a house divided” in its original context, just before the start of the Civil War.

NOTE: Because it provides the central concept of this set of resources, I’ve included it last (although it predates John Brown’s speech above.)

Illinois Republican State Convention, Springfield, Illinois June 16, 1858Abraham Lincoln

Mr. President and Gentlemen of the Convention. If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do, and how to do it.

We are now far into the fifth year, since a policy was initiated, with the avowed object, and confident promise, of putting an end to slavery agitation. Under the operation of that policy, that agitation has not only, not ceased, but has constantly augmented.

In my opinion, it will not cease, until a crisis shall have been reached, and passed -

"A house divided against itself cannot stand."

I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.

I do not expect the Union to be dissolved - I do not expect the house to fall - but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.

1- John Brown's Raid (US National Park Service). (2021, July 30). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/articles/john-browns-raid.htm

- John Brown's Raid on Harper's Ferry. (n.d.). Ohio History Central. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/John_Brown%27s_Raid_on_Harper%27s_Ferry

CitePrintShare“House Divided Speech - Lincoln Home National Historic Site (US National Park Service).” National Park Service, 10 April 2015, https://www.nps.gov/liho/learn/historyculture/housedivided.htm.

An excerpt from John Brown's address to the court after hearing his guilty verdict, 1859John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry fits into Lincoln’s foretelling of a crisis and further spurs the start of the Civil War. Brown’s speech to the courtroom highlights his sense of what, in this moment, constitutes justice and injustice.

John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry: John Brown, an abolitionist, led the Raid on Harper’s Ferry, a federal arsenal, in an effort to start an armed insurrection against slavery. The event, which took place after Lincoln’s “a house divided” speech, serves as an example of the violence Lincoln foretold. Brown echoed Lincoln’s sentiments, explaining in 1859, “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.” Brown and his followers were trapped and arrested, and Brown was tried and found guilty of treason.

“I have, may it please the court, a few words to say. In the first place, I deny everything but what I have all along admitted--the design on my part to free the slaves. I intended certainly to have made a clean thing of that matter, as I did last winter when I went into Missouri and there took slaves without the snapping of a gun on either side, moved them through the country, and finally left them in Canada. I designed to have done the same thing again on a larger scale. That was all I intended. I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.I have another objection; and that is, it is unjust that I should suffer such a penalty. Had I interfered in the manner which I admit...had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends--either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class--and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.”

CitePrintShare“An excerpt from John Brown's address to the court after hearing his guilty verdict, 1859.” Digital Public Library of America, https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/john-brown-s-raid-on-harper-s-ferry/sources/1722.

The Women’s Rights Convention of 1853TranscriptQuotation beneath the photograph: "If de fust woman God ever made was strong enough to turn de world upside down all alone, dese women all togedder ought to be able to turn it back and get it right side up agin."

This photograph pairs with the text in the row below from the Women’s Rights Convention of 1853, when Sojourner Truth spoke to the group.

The Women’s Rights Convention: The Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 is a significant event in the fight for women’s rights and for women’s suffrage, though activists at the convention itself debated whether suffrage should be the center point of their platform. In addition, the Seneca Falls Convention is now widely understood to represent some tension between the women’s rights movement and the abolitionist movement; some activists at the time felt that the right to vote should not go to black men before white women. In this collection of documents, Sojourner Truth’s speech to a smaller, subsequent convention – one held in New York in 1853 – is included, largely because of the critical role Sojourner Truth plays in demonstrating the importance of the intersectionality of both the women’s rights and abolitionist movements.

1- On this day, the Seneca Falls Convention begins. (2021, July 19). National Constitution Center. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/on-this-day-the-seneca-falls-convention-begins and More Women's Rights Conventions - Women's Rights National Historical Park (US National Park Service). (n.d.). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/more-womens-rights-conventions.htm and Proceedings of the Woman's Rights Convention held at the Broadway Tabernacle, in the city of New York, on Tuesday and Wednesday, Sept. 6th and 7th, 1853. (n.d.). Library of Congress. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.loc.gov/item/93838289/

CitePrintShare“Sojourner Truth.” The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/rbcmiller001306/.

Education for American Democracy

This lesson helps dispel prevailing stereotypes and generalizing cultural representations of American Indians by providing culturally-specific information about the contemporary as well as historical cultures of distinct tribes and communities within the United States.

The Roadmap

National Endowment for the Humanities

Ths primary source set focuses on material culture produced about and by American Indians. The information and materials in the set can be used as a jumping off point for teachers looking to access resources provided by the Library of Congress related to the topic.

The Roadmap

Emerging America - Collaborative for Educational Services

On the occasion of the launch of the Mandela Children’s Fund, Nelson Mandela said, “There can be no keener revelation of a society's soul than the way in which it treats its children.” Children have often been caught up and played a role in the ideological and political movements that have taken place throughout U.S. History. What can we learn about these political and ideological movements through the lens of children and their experiences? When we frame our study of the past through the experiences of children and adolescents, we create pathways for connection and curiosity for our students. There are many ways you might use these sources in your curriculum. Use these sources individually, as you cover a particular era, or collectively, as students examine change and continuity in the experiences of children and teens over time. Sources are indexed below by theme and era and each source includes a brief description as well as guiding questions for use in the classroom.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by SubthemeEducation and its Impact on Children and Teens (12)Children and Public Activism (7)

- Primary Resources by Era/DateColonial Era (3)Nineteenth Century (3)1930s - 1940s (3)1940s, 50s, and 60s (9)Early Twentieth Century and WWI (6)

- All 24 Primary ResourcesContract for the Indenture of Elizabeth Fortune, Aged 9, 1723Contract for the Indenture of Elizabeth Fortune, Aged 9, 1723Transcript

John Fortune and Maria his wife have by these presents put, placed, and bound their daughter Elizabeth Fortune aged nine years the first day of March last past as an apprentice with the Said Elizabeth Sharpas

as an apprentice with her, the said Elizabeth Sharpas, to dwell from the day of the date of these presents for and during the term of Nine Years…The Said Elizabeth Fortune unto according to her power, wit, and ability and honestly and obediently in all things shall behave herself towards her said Mistress and all hers and shall not contract matrimony during the said Term.

Elizabeth Sharpas for her part promises, Covenants, agrees that she the said Elizabeth Sharpas apprenticed Elizabeth Fortune in the art and skill of housewifery.

This document provides a glimpse into the experiences of colonial children who spent much of their childhood working for families that were not their own. This indenture arraignment also highlights the kinds of skills and education that were valued for girls. Namely, Elizabeth Fortune is said to receive training in the “art of housewifery” in exchange for her service.

CitePrintShare“Indenture of Elizabeth Fortune, September 10, 1723,” Women & the American Story, https://wams.nyhistory.org/settler-colonialism-and-revolution/settler-colonialism/children-at-work/#. Accessed 1 April 2022.

Needlework by Sarah Anne Janeway, 1783 - Training for domestic workSewn Sampler made by 11-year-old Sarah Anne Janeway, 1783Young colonial girls raised in wealthy households were trained in the skills of a housewife early on. Samplers like this one displayed a girl's aptitude for needlework and could be hung as a piece of art in a family household.

CitePrintShare“Symbols of Accomplishment - Women & the American Story.” Women & the American Story, https://wams.nyhistory.org/settler-colonialism-and-revolution/settler-colonialism/symbols-of-accomplishment/#. Accessed 1 April 2022.

A New England Primer, 1803 - The role of religion in educationIn colonial New England, a primer like this one may have been in use as early as 1690. Children first learned their ABCs and basic literacy through primers. Since the Bible was seen as the primary means through which a child would attain literacy, these primers would often incorporate religious themes and morals.

CitePrintShareWestminster Assembly. “The New-England primer,” Boston: Printed for and sold by A. Ellison, in Seven-Star Lane, 1773. Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/22023945/>. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Perry Lewis (b. 1850), formerly enslaved, recounts his childhood in Baltimore, M.D. - Enslaved children and lack of access to educationPerry Lewis (b. 1850), formerly enslaved, recounts his childhood in Baltimore, M.D.TranscriptAs you know the mother was the owner of the children that she brought into the world Mother being a slave made me a slave. She cooked and worked on the farm, ate whatever was in the farmhouse and did her share of work to keep and maintain the Tolsons.

They being poor, not having a large place or a number of slaves to increase their wealth, made them little above the free colored people and with no knowledge, they could not teach me or anyone else to read…

In my childhood days, I played marbles, this was the only game I remember playing. As I was on a small farm, we did not come in contact much with other children and heard no childrens’ songs. I therefore do not recall the songs we sang.

Records from the Federal Writers Project are of immense importance in documenting and preserving the experiences of those who survived enslavement. ; Lewis’ account includes reference to the concept of hypodescent, which allowed intergenerational, chattel slavery to persist in the U.S. Lewis also makes note of his lack of access to education and some memories of his childhood.

1- Miletich, Patricia. “Religion and Literacy in Colonial New England | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History |, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/lesson-plan/religion-and-literacy-colonial-new-england. Accessed 2 April 2022.

- For more on the Federal Writer’s Project see Smith, Clint. “The Value of the Federal Writers' Project Slave Narratives.” The Atlantic, 9 February 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/03/federal-writers-project/617790/. Accessed 19 April 2022.

CitePrintShareFederal Writers' Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 8, Maryland, Brooks-Williams. 1936. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/mesn080/>. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Before and After Photos of Children enrolled in Carlilse Residential Indian School, 1890s - Residential School SystemOne of the “before-and-after-education” photographs of Sioux boys taken before arriving at boarding school in the 1890s.At Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, and other residential schools like it, Native American children and teens were required to give up their tribal traditions and culture. Carlisle opened in 1879 as the first government-run residential school, aimed at forcing Indigenous youth to assimilate to White culture. These before and after photos were taken as a way to demonstrate the efforts at assimilation.

1- “Richard Henry Pratt Carlisle Indian School.” Carlisle Indian School Project, https://carlisleindianschoolproject.com/past/. Accessed 2 April 2022.

CitePrintShareImage 1: "Sioux boys as they arrived at Carlisle," Digital Public Library of America, http://dp.la/item/d7ca78d98ae563bfefd20c2620613c8b. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Image 2: "Sioux boys 3 years after arriving at Carlisle," Digital Public Library of America, http://dp.la/item/f7b6ae7adfd4a9c9ecbceaf3af5fa8b5. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Sample Program For One Week - Residential School SystemSample daily program for one week at an Indian school, 1914Life for a student at the Carlisle Indian School was highly regimented and militaristic, signaling the government’s influence on the school’s mission and identity. This source, paired with the images above, offers a glimpse into the daily experience of those enrolled in this program as well as information about the aims of the federal government in establishing institutions such as Carlisle.

CitePrintShare“Cover letter, January 23, 1914, with attached sample daily program for one week at an Indian school”; 1/1914; Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group 75. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/cover-letter-january-23-1914-with-attached-sample-daily-program-for-one-week-at-an-indian-school. Accessed March 24, 2022.

Mary Ann Yahiro recites the Pledge of Allegiance at Raphael Weill School in San Francisco before being sent to Topaz internment camp in Utah, April 1942 - Japanese IntenmentMary Ann Yahiro, center, recites the Pledge of Allegiance at Raphael Weill School in San Francisco in April 1942 before being sent to Topaz internment camp in Utah.This photograph shows a group of children in the Weil Public School reciting the pledge of allegiance to the U.S. flag. The young girl in the front row center is Helen Mihara. A few months before this image was taken, Helen’s father, a San Francisco businessman, was arrested and detained in a Department of Justice camp for “enemy aliens.” Soon after this image was taken, Helen and her mother were placed in Tule Lake Relocation Center. Her mother later died in detention.

1- “San Francisco, Calif., April 1942 - Children of the Weill public school, from the so-called international settlement, shown in a flag pledge ceremony. Some of them are evacuees of Japanese ancestry who will be housed in War relocation authority centers for.” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2001705926/. Accessed 5 April 2022.

CitePrintShareLange, Dorothea, photographer. San Francisco, Calif., April- Children of the Weill public school, from the so-called international settlement, shown in a flag pledge ceremony. Some of them are evacuees of Japanese ancestry who will be housed in War relocation authority centers for the duration. [April] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2001705926/>. Accessed April 10, 2022.

TIME Magazine Feature on the American “teen-ager," 1944 - American Teenage Girls“The Invention of the American “teen-ager,” 1944Although it is not a certainty, some historians believe that the concept of the American “teenager” originated sometime in the 1940s. A liminal age, the teenager was neither child nor adult. This 1944 TIME Magazine article detailed the “life of the American Teenager” by photojournalist Nina Leen. The full article offers a glimpse into the perception of teens but also offers opportunities for students to consider the rise of the middle class, social status, and race in the middle of the twentieth century.

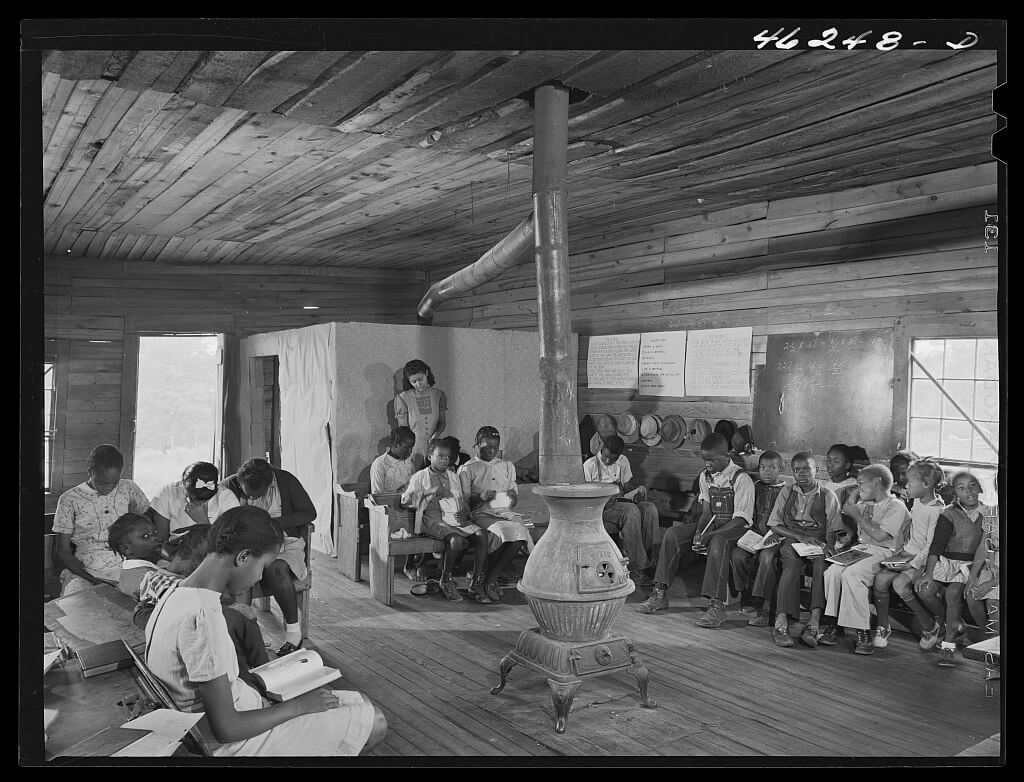

Separate but Unequal: Two classrooms before Brown v. Board of Education, Georgia, 1941 - School SegregationSchool segregation was among the most central concerns of the Civil Rights Movement since the 1930s. Activists for school integration argued that separate was not equal and every child, regardless of race, was entitled to education in a safe learning environment. These two images depict daily life in segregated classrooms in the same year, 1941. Brown v. Board of Education would not be passed for more than a decade.

1- “Recovery Programs.” Recovery Programs | DPLA, https://dp.la/exhibitions/new-deal/recovery-programs/farm-security-administration?item=409. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareImage 1: Delano, J., photographer. (1941) Veazy, Greene County, Georgia. The one-teacher Negro school in Veazy, south of Greensboro. United States Greene County Georgia Veazy, 1941. Oct. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017796657/. Accessed April 10, 2022.

Image 2: Delano, J., photographer. (1941) Siloam, Greene County, Georgia. Classroom in the school. United States Greene County Siloam Georgia, 1941. Oct. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017796554/. Accessed April 10, 2022.

Telegram from Parents of the Little Rock Nine to President Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1957-58 - School IntegrationTelegram from Parents of the Little Rock Nine to President Dwight D. EisenhowerWritten three years after the passage of Brown v. Board of Education, this telegram to President Eisenhower details the feelings of parents of the Little Rock Nine, who were a part of the busing program to integrate the Little Rock school system. The Little Rock Nine were the first African American students to enter Little Rock’s Central High School in Arkansas. The parents note that because of the supreme court ruling their “faith in democracy” had been renewed.

1- “The Little Rock Nine.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/little-rock-nine. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareTelegram from Parents of the Little Rock Nine to President Dwight D. Eisenhower; 10/1957; OF 142-A-5 Negro Matters - Colored Question (5), 1957 - 1958; Official Files, 1953 - 1961; Collection DDE-WHCF: White House Central Files (Eisenhower Administration), 1953 - 1961; Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Abilene, KS. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/telegram-parents-little-rock-nine-to-president-eisenhower. Accessed April 1, 2022.

African American children on their way to PS204, 82nd Street, and 15th Avenue, pass mothers protesting the busing of children to achieve integration, 1965 - School IntegrationAfrican American children on their way to PS204, 82nd Street, and 15th Avenue, pass mothers protesting the busing of children to achieve integrationEven after the passage of Brown v. Board of Education, school integration was protested. This image shows African American children entering their new school while white mothers protest school integration

CitePrintShareDemarsico, Dick, photographer. African American children on way to PS204, 82nd Street and 15th Avenue, pass mothers protesting the busing of children to achieve integration (1965). Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2004670162/>. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Audio Recording: Conversation with 11 and 12-year-old black females, Meadville, Mississippi, 1973 - Daily life for two pre-teens in DetriotThis conversation was originally recorded as part of an effort to archive regional dialects by the Library of Congress. It also provides a glimpse into the daily lives of pre-teen girls, including racial discrimination they faced in their school community.

Audio Recording: Conversation with 11 and 12-year-old black females, Meadville, Mississippi

CitePrintShareUnidentified, and Walt Wolfram. Conversation with 11 and 12-year-old black females, Meadville, Mississippi. to 1973, 1972. Audio. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/afccal000213/>. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Mother Jones and Children Laborers go on Strike, 1903Mother Jones and Children Laborers go on Strike, 1903In July of 1903, Mother Jones led a march from Philadelphia to the home of President Rosevelt to protest the unsafe labor conditions of children working in mills. The story of Mother Jones and the children who accompanied her on her march showcases not only youth activism but also women in the labor movement at the turn of the century.

1- Lauren Cooper. “July 7, 1903: March of the Mill Children.” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/mother-jones-march-mill-children/. Accessed 3 April 2022.

CitePrintShare"Mother" Jones and her army of striking textile workers starting out for their descent on New York The textile workers of Philadelphia say they intend to show the people of the country their condition by marching through all the important cities”; 1903; Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2015649893/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Child Labor Standards, 1916Child Labor StandardsThis ad was created after the passage of the Keating-Own Child Labor Act of 1916. This act limited the working hours of children and placed an age requirement of the age of 16 for any working child. It also forbade the interstate sale of goods produced in factories that employed child labor.

CitePrintShare"Child Labor Standards"; ca. 1941-1945; Records of the Office of War Information, Record Group 208. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/child-labor-standards. April 1, 2022.

Girl Scouts and the War EffortGirl Scout Troup Plants a Victory Garden, 1917Girl Scout Pledge Card to Save for a Soldier, 1914After the US declared war in 1917, children were encouraged to support the war efforts. The Girl Scouts of America provided an opportunity for girls to become involved in volunteer work for the war effort. Organizations like the Girls Scouts and 4H typically trained girls for domestic work. Skills like sewing and first-aid were put to use in new ways for members of the Girl Scouts and 4H during WWI. Here, scouts planted a Victory Garden. Victory gardens, or liberty gardens, first appeared during WWI. The federal government encouraged citizens to plant vegetable gardens to mitigate any food shortages that resulted from the war.

1- Lauren Cooper. “July 7, 1903: March of the Mill Children.” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/mother-jones-march-mill-children/. Accessed 3 April 2022.

- Spring, Kelly A. “Girls' Volunteer Groups during World War I.” National Women's History Museum, https://www.womenshistory.org/resources/general/girls-volunteer-groups-during-world-war-i. Accessed 3 April 2022.

CitePrintShareImage 1: Harris & Ewing, photographer. NATIONAL EMERGENCY WAR GARDENS COM. GIRL SCOUTS GARDENING AT D.A.R. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2016867777/>. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Image 2: “Girl Scout Pledge Card "To Save for a Solder”. 1914. Girl Scout Archive Management Center. https://archives.girlscouts.org/Detail/objects/64958. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Boy Scouts as Bond Workers, 1917Boy Scouts as Bond Workers, 1917Boyscouts, like Girl Scouts, volunteered in the war effort during both WWI and II. Here, scouts who were too young to go to combat sell war bonds.

CitePrintShareBain News Service, Publisher. Boy Scouts as bond workers. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2014704734/>. Accessed April 10, 2022.

12-Year-Old Girl at the March on Washington, 196312-Year-Old Girl at the March on WashingtonOn August 28, 1963, thousands took part in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The March was instigated by a continuing lack of jobs for African Americans and the persistence of segregation. The march was influential in pressuring President John F. Kennedy to draft a strong civil rights bill. This photo depicts Edith Lee-Payne on her twelfth birthday. Edith attended the March with her mother.

1- “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom | The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute.” The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute |, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/march-washington-jobs-and-freedom. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintSharePhotograph 306-SSM-4C-61-32; Young Woman at the Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. with a Banner; 8/28/1963; Miscellaneous Subjects, Staff and Stringer Photographs, 1961 - 1974; Records of the U.S. Information Agency, Record Group 306; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/girl-march-on-washington-banner. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Protests in support of the 26th Amendment, 1969Protests in support of the 26th AmendmentThe 26th Amendment to the Constitution allowed for those 18 years old or older to vote in elections. Support for decreasing the voting age from 21 to 18 increased during World War II, as young men were conscripted to fight in the war as young as 18 but could not yet vote. This image depicts youth protestors in support of the 26th amendment.

1- “The 26th Amendment | Richard Nixon Museum and Library.” Nixon Presidential Library, 17 June 2021, https://www.nixonlibrary.gov/news/26th-amendment. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShare“Demonstration for reduction in voting age, Seattle, 1969”; Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, Museum of History & Industry, Seattle; https://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/digital/collection/imlsmohai/id/1715/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Little Spinner in Globe Cotton Mill, Augusta, Ga., 1909Little Spinner in Globe Cotton Mill, Augusta, Ga., 1909Images of children laborers at the turn of the century reveal the experiences of children who spent most of their days working in the oftentimes harsh and unsafe conditions of urban factories. After the Civil War, as industry grew in urban areas, children often worked in factories, in markets, and on the streets as vendors.

Children Working in a Textile Mill in Georgia, 1909Children Working in a Textile Mill in GeorgiaLike the image above, this source shows a young child operating machinery that he is not even tall enough to reach. Images like these and the one above were captured by activists for child labor laws. The Child labor standards act would be passed in 1916

1- Schuman, Michael. “History of child labor in the United States—part 1: little children working: Monthly Labor Review: US Bureau of Labor Statistics.” Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2017/article/history-of-child-labor-in-the-united-states-part-1.htm. Accessed 19 April 2022.

CitePrintSharePhotograph 102-LH-488; Bibb Mill No. 1, Macon, Ga.; 1/19/1909; Bibb Mill No. 1, Macon, Ga. Many youngsters here. Some boys and girls were so small they had to climb up onto the spinning frame to mend broken threads and to put back the empty bobbins.,; Records of the Children's Bureau, Record Group 102; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/bibb-mill. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Spread from Look magazine on sharecropping children, 1937Page from Look magazine, 1937 on sharecropping childrenThis magazine spread on sharecropping children was published the same year that President Rosevelt established the Farm Security Administration. The FSA was a New Deal agency that provided assistance and relief to agricultural workers impacted by drought and the Great Depression.

1- “Gardening for the Common Good.” Smithsonian Libraries, https://library.si.edu/exhibition/cultivating-americas-gardens/gardening-for-the-common-good. Accessed 19 April 2022.

CitePrintSharePages 18 and 19 of March Look magazine. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2017760274/>. April Accessed April 10, 2022.

Boys playing marbles, Farm Security Administration labor camp, Robstown, Texas, 1944Boys playing marbles, Farm Security Administration labor camp, Robstown, Texas, 1944During the Great Depression, The Farm Security Administration attempted to aid workers and farmers by setting up housing camps, providing loans and training to workers, among other forms of assistance. This source shows a group of children playing marbles in one of the FSA labor camps in Texas, offering a glimpse into daily life and play for children living through the Great Depression.

CitePrintShareRothstein, A., photographer. (1942) Boys playing marbles, FSA ... labor camp, Robstown, Texas. United States Robstown Texas, 1942. Jan. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017877649/. Accessed April 10, 2022.

School Closures during Little Rock Nine: Girls learn from Home, 1958 - School IntegrationSchool Closures during Little Rock 9: three pajama-clad white girls being educated via television during the period that the Little Rock schools were closed to avoid integration.In September 1958, Governor Faubus of Arkansas closed all Little Rock public high schools as a result of unrest due to integration. Known as the “Lost Year,” both teachers and students were blocked from their school buildings. This image shows three girls learning “remotely” during that time and offers a glimpse of the efforts to maintain continuity of education in the midst of upheaval.

1- “The Little Rock Nine.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/little-rock-nine. Accessed 4 April 2022.

- “Sept. 12, 1958: Little Rock Public Schools Closed.” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/little-rock-schools-closed/. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareO'Halloran, T. J., photographer. (1958) Little Rock, Ark. Attempts to reopen schools / TOH. Arkansas Little Rock, 1958. Sept. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003654390/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Letter from Linda Kelly, Sherry Bane, and Mickie Mattson to President Dwight D. Eisenhower Regarding Elvis Presley, 1953-1961Letter from Linda Kelly, Sherry Bane, and Mickie Mattson to President Dwight D. Eisenhower Regarding Elvis Presley, 1953-1961Celebrities were no exception to the draft during the Vietnam War. Elvis Presley joined the army in 1958 and, in this letter, three girls from Nevada ask President Eisenhower not to shave off his sideburns. This source offers a window into the lives of American teens as well as an example of the role teens played in the evolution and development of American pop culture.

1- Cosgrove, Ben. “The Invention of Teenagers: LIFE and the Triumph of Youth Culture.” Time.com, TIME, 28 September 2013, https://time.com/3639041/the-invention-of-teenagers-life-and-the-triumph-of-youth-culture/. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareBane, Sherry Author, Linda Author Kelly, and Mickie Author Mattson. Letter from Linda Kelly, Sherry Bane, and Mickie Mattson to President Dwight D. Eisenhower Regarding Elvis Presley. [Place of Publication Not Identified: Publisher Not Identified, 1958] Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2021667581/> Accessed April 4, 2022.

- Additional Resources

- Teacher's Guides and Analysis Tool | Getting Started with Primary Sources | Teachers | Programs | Library of Congress

- Document Analysis Overview | National Archives

- Activity Tools | DocsTeach

- Primary Source Activity Guide | EAD Team

Education for American Democracy

This Civil Rights unit covers the early days of the expansion of slavery in the United States through the momentous 1950s and 60s and into the modern Civil Rights Movement. Use primary documents, readings, activities and more to introduce your students to key concepts, events, and individuals of this facet of American history.

The Roadmap

iCivics, Inc.

This 8-lesson Civil Rights unit covers the early days of the expansion of slavery in the United States through the momentous 1950s and 60s and into the modern Civil Rights Movement. Use primary documents, readings, activities and more to introduce your students to key concepts, events, and individuals of this facet of American history.

The Roadmap

iCivics, Inc.

The African-American Civil Rights movement is typically seen as having taken place mostly in the 1950s and 60s, when a confluence of social and economic factors enabled political change. The movement, however, has much deeper roots, and thus our toolkit starts in the 19th Century, some two generations before leaders like King, Parks, and others were born. Viewing the Civil Rights movement as a generational one provides a broader perspective on the ideas and people at the foundation of this work to achieve “a more perfect union” for all Americans.

The Roadmap

Ashbrook/TeachingAmericanHistory

In this lesson, students will analyze the visual and literary visions of the New World that were created in England during the early phases of colonization, and the impact they had on the development of the patterns of colonization that dominated the early 17th century. This lesson will enable students to interact with written and visual accounts of this critical formative period at the end of the 16th century, when the English view of the New World was being formulated, with consequences that we are still seeing today.

The Roadmap

National Endowment for the Humanities

This unit uses primary documents and images to discover the ways state and local governments restricted the newly gained freedoms of African Americans after the Civil War. Students compare, contrast, and analyze post-war legislation, court decisions (including Plessy v. Ferguson), and a political cartoon by Thomas Nast to understand life in Jim Crow states.

The Roadmap

iCivics, Inc.

Students will examine the life and actions of John Brown through primary sources and historical narrative.

The Roadmap

Bill of Rights Institute

In many ways, the history of the US has been shaped by the movement of people. People came to America searching for gold as early as the fifteenth century, while others sought religious freedom and increased economic mobility. Millions of others were forced here against their will. This primary source set will spotlight the causes and impacts of migration and movement, focusing primarily on the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Contexts include slavery, Black migration after the abolition of slavery, immigration to the United States and the immigrant experience, Dust Bowl migration, westward movement by European Americans, and Indigenous relocation and removal. Recognizing that movement often occurs after and during transition or change, this source kit will also highlight several catalysts that brought about migration and movement, some occurring at the same moment in history. These primary sources will also present varying attitudes and perceptions toward migration and movement spanning this period. This topic could be expanded by comparing migration patterns as early as the colonial period and as recent as today.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by Era/Date1700s (1)1800s (16)1900s (12)

- All 29 Primary ResourcesU.S. Constitution, Article 1, Section 9 (1787)

This clause of the United States Constitution is seen as both a temporary protection for the slave trade and as a clear indication that enslaved people were not considered United States citizens under the Constitution.

United States Constitution, Article I: Legislative BranchSection 9 : Powers Denied Congress Clause 1 Migration or Importation The Migration or Importation of such Persons as any of the States now existing shall think proper to admit, shall not be prohibited by the Congress prior to the Year one thousand eight hundred and eight, but a Tax or duty may be imposed on such Importation, not exceeding ten dollars for each Person.

CitePrintShare“Article I Section 9 | Constitution Annotated | Congress.gov | Library of Congress.” Constitution Annotated, https://constitution.congress.gov/browse/article-1/section-9/.

A letter from President Andrew Jackson to the Cherokee Nation about the benefits of voluntary removal, March 16, 1835A letter from President Andrew Jackson to the Cherokee Nation about the benefits of voluntary removal, March 16, 1835TranscriptMy Friends:

I have long viewed your condition with great interest. For many years I have been acquainted with your people, and under all variety of circumstances, in peace and war. Your fathers were well known to me, and the regard which I cherished for them has caused me to feel great solicitude for your situation….

You are now placed in the midst of a white population…. Most of your people are uneducated, and are liable to be brought into collision at all times with their white neighbors. Your young men are acquiring habits of intoxication. With strong passions, and without those habits of restraint which our laws inculcate and render necessary, they are frequently driven to excesses which must eventually terminate in their ruin. The game has disappeared among you, and you must depend upon agriculture and the mechanic arts for support. And, yet, a large portion of your people have acquired little or no property in the soil itself, or in any article of personal property which can be useful to them. How, under these circumstances, can you live in the country you now occupy? Your condition must become worse and worse, and you will ultimately disappear, as so many tribes have done before you.

Of all this I warned your people, when I met them in council eighteen years ago. I then advised them to sell out their possessions east of the Mississippi and to remove to the country west of that river. This advice I have continued to give you at various times from that period down to the present day, and can you now look back and doubt the wisdom of this counsel?....

President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act into law in 1830. This law granted the President the ability to exchange land west of the Mississippi for Indigenous territories within the boundaries of existing states. An additional act was passed in 1834. This act designated land, including what would later become the state of Oklahoma, as Indian Territory. As a result of the precedent set by these acts, over sixty tribes were either willingly or forcibly removed from their lands over the next fifty years.

CitePrintShareJackson, Andrew, “To the Cherokee tribe of Indians east of the Mississippi River,” Digital Public Library of America, https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/cherokee-removal-and-the-trail-of-tears/sources/1506

George Catlin, Wi-jún-jon, Pigeon's Egg Head (The Light) Going To and Returning From Washington (1837-1839)The Smithsonian American Art Museum explains: “Catlin mistranslated Ah-jon-jon, whose name means ‘The Light,’ as ‘Pigeon's Egg Head.’ The Light was an Assiniboine leader who was invited in 1831 to represent his tribe in Washington. During a winter in the nation's capital, he traded his native dress for European clothes and customs. In Catlin's before-and-after portrait, the once proud warrior, with a liquor bottle in his pocket, swaggers in high-heeled boots and carries a fan and umbrella. For Catlin, this transformation illustrated the tragic gulf between Native American and white cultures.”

CitePrintShareGeorge Catlin, Wi-jún-jon, Pigeon's Egg Head (The Light) Going To and Returning From Washington, 1837-1839, oil on canvas, Smithsonian American Art Museum, Gift of Mrs. Joseph Harrison, Jr., 1985.66.474. Retrieved from https://americanart.si.edu/artwork/wi-jun-jon-pigeons-egg-head-light-going-and-returning-washington-4317.

Letter from Chief John Ross, "To the Senate and House of Representatives" (1836)TranscriptA spurious Delegation, in violation of a special injunction of the general council of the nation, proceeded to Washington City with this pretended treaty, and by false and fraudulent representations supplanted in the favor of the Government the legal and accredited Delegation of the Cherokee people, and obtained for this instrument, after making important alterations in its provisions, the recognition of the United States Government. And now it is presented to us as a treaty, ratified by the Senate, and approved by the President [Andrew Jackson], and our acquiescence in its requirements demanded, under the sanction of the displeasure of the United States, and the threat of summary compulsion, in case of refusal. It comes to us, not through our legitimate authorities, the known and usual medium of communication between the Government of the United States and our nation, but through the agency of a complication of powers, civil and military.

By the stipulations of this instrument, we are despoiled of our private possessions, the indefeasible property of individuals. We are stripped of every attribute of freedom and eligibility for legal self-defense. Our property may be plundered before our eyes; violence may be committed on our persons; even our lives may be taken away, and there is none to regard our complaints. We are denationalized; we are disfranchised. We are deprived of membership in the human family! We have neither land nor home, nor resting place that can be called our own. And this is effected by the provisions of a compact which assumes the venerated, the sacred appellation of treaty.

In 1835, in the “Treaty of New Echota,” a group of Cherokees – without consent of the majority of their nation – agreed that the Cherokee people would move West and vacate their land. This letter, a protest against the Treaty, was sent by Chief John Ross and other Cherokee leaders to Congress in an effort to declare that treaty invalid.

CitePrintShare“Transcript for papers-of-john-ross-original-text.” National Museum of the American Indian, https://americanindian.si.edu/nk360/removal-cherokee/transcripts/papers-of-john-ross-original-text.html.

“Africans in America/Part 4/John Ross letter.” PBS, https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part4/4h3083t.html

Physician's Monthly Report of Emigrating Cherokees at Chadata (1838)During the fall and winter of 1838 and 1839, the Cherokees were forcibly marched from their lands. Known as the “Trail of Tears,” this forced removal resulted in the deaths of thousands of Cherokee. The Choctaw, the Chickasaw, the Creek, and the Seminole also were forced to travel along the trail of tears.

CitePrintSharePhysician's Monthly Report of Emigrating Cherokees at Chadata in August 1838; 8/1838; Special Files, ca. 1840 - ca. 1904; Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group 75; National Archives Building, Washington, DC. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/physicians-report-cherokees, February 12, 2022]

Drexler, K. (2019, January 22). Research Guides: Indian Removal Act: Primary Documents in American History: Introduction. Library of Congress. Retrieved February 1, 2022, from https://guides.loc.gov/indian-removal-act.

Death of Captain Ferrer, the Captain of the Amistad (1839)In 1839, the enslaved people aboard the Amistad were captured by Portuguese slave traders in Sierra Leone, and they were being taken to a Caribbean plantation. The enslaved Africans seized control of the ship, killed two of their captors, and ordered the ship to sail to Africa, but it was seized off of the coast of Long Island and the enslaved Africans were brought to trial in Connecticut. As the National Archives explains, “Had it not been for the actions of abolitionists in the United States, the issues related to the Amistad might have ended quietly in an admiralty court. But they used the incident as a way to expose the evils of slavery and generate significant opposition to the practice.” In an appeal before the U.S. Supreme Court, John Quincy Adams “passionately and eloquently defended the Africans' right to freedom on both legal and moral grounds, referring to treaties prohibiting the slave trade and to the Declaration of Independence. The Supreme Court decided in favor of the Africans, stating that they were free individuals.”

CitePrintShareSchomburg Center for Research in Black Culture, Manuscripts, Archives, and Rare Books Division, The New York Public Library. (1840). Death of Captain Ferrer, the Captain of the Amistad, July 1839. Retrieved from https://digitalcollections.nypl.org/items/510d47e3-1a6d-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99

“The Amistad Case | National Archives.” National Archives |, 2 June 2021, https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/amistad#background.

Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo (1848)TranscriptFebruary 2, 1848

In the name of Almighty God

The United States of America and the United Mexican States animated by a sincere desire to put an end to the calamities of the war which unhappily exists between the two Republics and to establish Upon a solid basis relations of peace and friendship, which shall confer reciprocal benefits upon the citizens of both, and assure the concord, harmony, and mutual confidence wherein the two people should live, as good neighbors have for that purpose appointed their respective plenipotentiaries, that is to say….

ARTICLE I

There shall be firm and universal peace between the United States of America and the Mexican Republic, and between their respective countries, territories, cities, towns, and people, without exception of places or persons….

ARTICLE VIII

Mexicans now established in territories previously belonging to Mexico, and which remain for the future within the limits of the United States, as defined by the present treaty, shall be free to continue where they now reside, or to remove at any time to the Mexican Republic, retaining the property which they possess in the said territories, or disposing thereof, and removing the proceeds wherever they please, without their being subjected, on this account, to any contribution, tax, or charge whatever.

Those who shall prefer to remain in the said territories may either retain the title and rights of Mexican citizens, or acquire those of citizens of the United States. But they shall be under the obligation to make their election within one year from the date of the exchange of ratifications of this treaty; and those who shall remain in the said territories after the expiration of that year, without having declared their intention to retain the character of Mexicans, shall be considered to have elected to become citizens of the United States….

ARTICLE IX

The Mexicans who, in the territories aforesaid, shall not preserve the character of citizens of the Mexican Republic, conformably with what is stipulated in the preceding article, shall be incorporated into the Union of the United States, and be admitted at the proper time (to be judged of by the Congress of the United States) to the enjoyment of all the rights of citizens of the United States, according to the principles of the Constitution; and in the mean time, shall be maintained and protected in the free enjoyment of their liberty and property, and secured in the free exercise of their religion without; restriction.

Article XI

Considering that a great part of the territories, which, by the present treaty, are to be comprehended for the future within the limits of the United States, is now occupied by savage tribes, who will hereafter be under the exclusive control of the Government of the United States, and whose incursions within the territory of Mexico would be prejudicial in the extreme, it is solemnly agreed that all such incursions shall be forcibly restrained by the Government of the United States whensoever this may be necessary; and that when they cannot be prevented, they shall be punished by the said Government, and satisfaction for the same shall be exacted all in the same way, and with equal diligence and energy, as if the same incursions were meditated or committed within its own territory, against its own citizens.

The Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo held a direct correlation to westward movement and migration. Americans forged west with the discovery of gold in 1848 at Sutter’s Mill in California which was the first major gold rush in the United States. By the following year, tens of thousands of “forty-niners” had come to the area in hopes of striking it rich. Most did not become wealthy in California, but many stayed there. The region continued to grow rapidly, and, in 1850, California became a state. With the expansion of available land and the gold rush, people from all over the USA and the world came and new businesses developed, including the pony express, transcontinental railroad jobs, Chinese laundry, the cattle industry, and free and enslaved Africans seeking freedom.

CitePrintShareTreaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. BlackPast, B. (2007, January 24). (1848) Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. BlackPast.org. https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/treaty-guadalupe-hidalgo/

https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/treaty-guadalupe-hidalgo/

Engraving of the Box in which Henry Box Brown Escaped from Slavery (1850)Engraving of the box in which Henry Box Brown escaped from slavery in Richmond, Va.The Fugitive Slave Act was passed in 1850 as part of the Compromise of 1850, a series of laws designed to ease sectional tensions between the North and South. The law benefitted southern enslavers by requiring northern law enforcement to assist in capturing and returning enslaved persons who had run away from their enslavers. Southern bounty hunters were also permitted to operate in the North. The law put both enslaved and free Blacks at risk. After the law was passed, thousands of freedom seekers attempted to escape to free states in the North and Canada as well, where they would be beyond the reach of the law.

CitePrintShareBrown, H. B. (1850) Engraving of the box in which Henry Box Brown escaped from slavery in Richmond, Va. Song, sung by Mr. Brown on being removed from the box. Boston Laing's Steam Press, 1-1-2 Water Street. 185-?. Boston. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.06501600/.

Parks, L. (1852) Poster offering fifty dollars reward for the capture of a runaway slave Stephen. Parks' Landing. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.00101200/.

Poster Offering Fifty Dollars Reward for the Capture of a Runaway Slave Stephen (1852)Poster Offering Fifty Dollars Reward for the Capture of a Runaway Slave Stephen (1852)Mining life in California--Chinese miners (1857)Mining life in California--Chinese miners (1857)During the peak of the Gold Rush, over 20,000 Chinese men immigrated to the United States to mine gold in California. Chinese immigrant labor contributed significantly to not only the mining industry, but also the expansion of the national railroad and the development of services supporting laborers. Nonetheless, xenophobic, anti-Chinese sentiment rose in California and nationally, ultimately leading to both the Chinese Massacre of 1871 (in which a violent mob lynched 18 Chinese men) and the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882.

CitePrintShare(1857) Mining life in California--Chinese miners. California, 1857. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2001700332/.

The Fugitive Slave Law and its Victims, excerpt (1861)The Fugitive Slave Law and its Victims, excerpt (1861)This book, The Fugitive Slave Law and its Victims, published in 1861, was an antislavery text, arguing for the abolition of slavery by providing accounts of the Fugitive Slave Laws’ effects and victims. The book was published by the American Anti-Slavery Society in New York.-

CitePrintShareMay, Samuel, “The fugitive slave law and its victims,” Digital Public Library of America, http://dp.la/item/2a8c4dcae9bc48e9da5bcd5e8269105a.

The Carpet-bagger (1868)The Carpet-bagger (1868)Popular images and music from the former Confederate states during Reconstruction created the image of the Northern “carpetbagger,” a derogatory term for an opportunistic outsider who has arrived from the Northern states to exploit the Southern states out of self-interest and greed.

CitePrintShareVon Rochow, A. & Garret, T. E. (1868) The Carpet-bagger. Balmer & Weber, Saint Louis. [Notated Music] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/ihas.200002527/.

Currier & Ives, Across the Continent, "Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way" (1868)Currier & Ives, Across the Continent, "Westward the Course of Empire Takes its Way" (1868)Images like this one helped to portray the West as vast, unpopulated, uncharted territory ready for U.S. expansion.

CitePrintShareCurrier & Ives, Ives, J. M. & Palmer, F. (1868) Across the continent, "Westward the course of empire takes its way" / J.M. Ives, del. ; drawn by F.F. Palmer. , 1868. [New York: Published by Currier & Ives, 152 Nassau Street] [Photograph]. Retrieved from Yale University Art Gallery, https://view.collections.yale.edu/m3/?manifest=https%3A//manifests.collections.yale.edu/yuag/obj/47239.

“Ho for Kansas!” Poster (1878)“Ho for Kansas!” Poster (1878)According to the Digital Public Library of America, “Benjamin Singleton established the Edgefield Real Estate and Homestead Association to help organize travel and settlement for African Americans departing Tennessee for Kansas.” Singleton was a formerly enslaved man who escaped to freedom in 1846, and he helped to organize the migration of approximately 300 African Americans to Kansas in 1877 - 1878. These migrants were not only seeking opportunity, but they were also fleeing the racial violence of white supremacists.

CitePrintShare“A broadside distributed by Benjamin Singleton advertising migration to Kansas, 1878.” Digital Public Library of America, https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/exodusters-african-american-migration-to-the-great-plains/sources/1662.

Chinese Exclusion Act (1882)The National Archives explains this law, the first in United States history to limit the ability of a designated group to immigrate into the country: “The Chinese Exclusion Act was approved on May 6, 1882….This act provided an absolute 10-year ban on Chinese laborers immigrating to the United States. For the first time, federal law proscribed entry of an ethnic working group on the premise that it endangered the good order of certain localities.

The Chinese Exclusion Act required the few non-laborers who sought entry to the United States (such as diplomatic officers) to obtain certification from the Chinese government that they were qualified to immigrate. But this group found it increasingly difficult to prove their status because the 1882 act defined laborers as "skilled and unskilled...and Chinese employed in mining." Thus very few Chinese could enter the country under the 1882 law…. Congress, moreover, refused state and federal courts the right to grant citizenship to Chinese resident aliens, although these courts could still deport them.”

An Act to execute certain treaty stipulations relating to Chinese.Whereas in the opinion of the Government of the United States the coming of Chinese laborers to this country endangers the good order of certain localities within the territory thereof: Therefore, Be it enacted by the Senate and House of Representatives of the United States of America in Congress assembled, That from and after the expiration of ninety days next after the passage of this act, and until the expiration of ten years next after the passage of this act, the coming of Chinese laborers to the United States be, and the same is hereby, suspended; and during such suspension it shall not be lawful for any Chinese laborer to come, or having so come after the expiration of said ninety days to remain within the United States.

SEC. 2. That the master of any vessel who shall knowingly bring within the United States on such vessel, and land or permit to be landed, any Chinese laborer, from any foreign port or place, shall be deemed guilty of a misdemeanor, and on conviction thereof shall be punished by a fine of not more than five hundred dollars for each and every such Chinese laborer so brought, and maybe also imprisoned for a term not exceeding one year.

SEC. 3. That the two foregoing sections shall not apply to Chinese laborers who were in the United States on the seventeenth day of November, eighteen hundred and eighty, or who shall have come into the same before the expiration of ninety days next after the passage of this act…

CitePrintShare“Chinese Exclusion Act (1882) | National Archives.” National Archives |, 17 January 2023, https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/chinese-exclusion-act.

Map showing Indian Reservations within the Limits of the United States (1883)Map showing Indian Reservations within the Limits of the United States (1883)The United States Government policies and practices of Indian removal forced multiple indigenous nations Westward, off of their land and into smaller, isolated reservations in the Western territories and states.

Indian Land Cessions in the United States (1899)Indian Land Cessions in the United States (1899)CitePrintShareRoyce, C. C. & Thomas, C. (1899) Indian land cessions in the United States. [Image] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/13023487/.

W. E. B. DuBois, Migration of Negroes. (ca. 1900)W. E. B. DuBois, Migration of Negroes. (ca. 1900)According to the Library of Congress, this chart was “prepared by [W.E.B.] Du Bois for the Negro Exhibit of the American Section at the Paris Exposition Universelle in 1900 to show the economic and social progress of African Americans since emancipation.”

CitePrintShareDu Bois, W. E. B. (ca. 1900) [The Georgia Negro] Migration of Negroes. Paris Georgia France, ca. 1900. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2013650427/.

Immigration Figures for 1903Immigration Figures for 1903In the early nineteenth century, many people left their home countries seeking a better life in the United States, perceived to be a land of opportunity and wealth. During the last decades of the nineteenth century, it is estimated that nearly 12 million immigrants arrived in the United States from Germany, Ireland, and England. In the 1900s immigrants from Italy arrived in large numbers.

CitePrintShareU. S. Commissioner-General Of Immigration. ... Immigration figures for 1903. From data furnished by the Commissioner-general of immigration. Comparison of the fiscal years ending and 1903. [Pdf] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/rbpe.07902500/.

The Americanese Wall - as Congressman Burnett Would Build It (1916)The Americanese Wall - as Congressman Burnett Would Build It (1916)While immigrants often came seeking a better life or escape from oppression and economic hardship, Immigrants faced many challenges in the United States. Lack of jobs and discrimination posed barriers to many immigrant communities and many faced pressures of assimilation and hostility.

CitePrintShareEvans, R. O. & Held, J. (1916) The Americanese wall - as Congressman Burnett would build it / Evans. "Watchful waiting"; A case where it is one of "My policies" / J. Held. United States, 1916. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2006681433/.

Make the Fourth of July Americanization Day (1915)Make the Fourth of July Americanization Day (1915)Throughout shifting immigration policies over the course of American history, there is also an ongoing debate about how best to assimilate new Americans. According to the Library of Congress, “though nativists may have abhorred the increasing ethnic diversity in the United States, others saw the opportunity to steep newcomers in American traditions. With four million Americans of Irish descent, hundreds of thousands of Jewish Americans with strong ties to Eastern Europe, and ten million citizens hailing from nations aligned with the Central Powers, organizations like the New York National Americanization Day Committee hoped to use patriotic holidays such as the Fourth of July as a means to unify the country's diverse populations.”

CitePrintShareMake the Fourth of July Americanization Day: Many Peoples—But One Nation. New York: National Americanization Day Committee, 1915–1919. Woodrow Wilson Papers, Manuscript Division, Library of Congress (082.00.00). https://www.loc.gov/exhibitions/world-war-i-american-experiences/about-this-exhibition/over-here/americanization/americanization-day/

“Relief units swamped by needy’s calls” (1932)“Relief units swamped by needy’s calls” (1932)During the Great Depression, hundreds of thousands of Mexicans and Mexican Americans were deported from the United States to Mexico. As unemployment increased during the 1930s, white Americans viewed Mexican immigrants and Mexican Americans as competition for scarce agricultural jobs and resources. In response, many local and state governments, often with the federal government's support, initiated a program of repatriating immigrants to Mexico. Some Mexicans, many of whom were recruited as farmworkers in the 1910s and 1920s, were offered free train rides to the border. In addition, Mexican Americans were coerced into giving up their jobs and land, forcing them to move to Mexico or find work elsewhere in the United States.

CitePrintShare“Relief units swamped by needy’s calls.” May 25, 1932. [Image] Retrieved from the Boulder County Latino History Project. https://bocolatinohistory.colorado.edu/newspaper/relief-units-swamped-by-needys-calls-1932-0

The Negro Motorist Green-Book (1936)The Negro Motorist Green-Book (1936)Between 1936 and 1967, The Green Book was published annually for African Americans traveling throughout the United States and North America. The Green Book’s original author, Victor Hugo Green, intended for the publication to act as a travel guide for African Americans during the Jim Crow Era, when laws prohibited many establishments from offering service to Black patrons. The Green Book offered suggestions to travelers seeking places and businesses which were safe for African Americans and which would treat Black patrons with dignity.

CitePrintShare(1936) The Negro motorist Green-book. New York City: V.H. Green. [Periodical] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2016298176/.

Dorothea Lange, “Migrants, family of Mexicans, on road with tire trouble. Looking for work in the peas.” (1936)Dorothea Lange, “Migrants, family of Mexicans, on road with tire trouble. Looking for work in the peas.” (1936)During the 1930s, the fallout from the Great Depression and environmental disaster struck the Great Plains region of the United States. Severe drought and resulting dust storms rendered the land in the Great Plains unfit for farming. Due to the drastic loss of jobs and income as well as the overwhelming amount of dust, which made living conditions unsafe and unbearable, millions of people left the Great Plains and headed west to California. Migrants faced a long and often dangerous journey to California as well as discrimination once they arrived.

CitePrintShareLange, D., photographer. (1936) Migrants, family of Mexicans, on road with tire trouble. Looking for work in the peas. California. United States California, 1936. Feb. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017759829/.