The curated resources linked below are an initial sample of the resources coming from a collaborative and rigorous review process with the EAD Content Curation Task Force.

Reset All

Reset All

The phrase “a house divided” comes from Abraham Lincoln’s speech to the Illinois Republican State Convention in 1858, when he describes a nation so badly torn between those that permitted slavery and those that prohibited it that it was on the brink of war. While the issue of slavery is understood to be central to the start of the Civil War, this set of resources is intended to introduce students to more details of the growing tension in the nation. Resources include information and images about expanding territory and the addition of new states to the union; voices of the abolitionist movement; political tension and acts of violence. It does not provide comprehensive coverage of these decades, but it helps to highlight that the growing tension was both multifaceted and happening across the entire nation.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by Decade1830s (4)1840s (3)1850s (9)

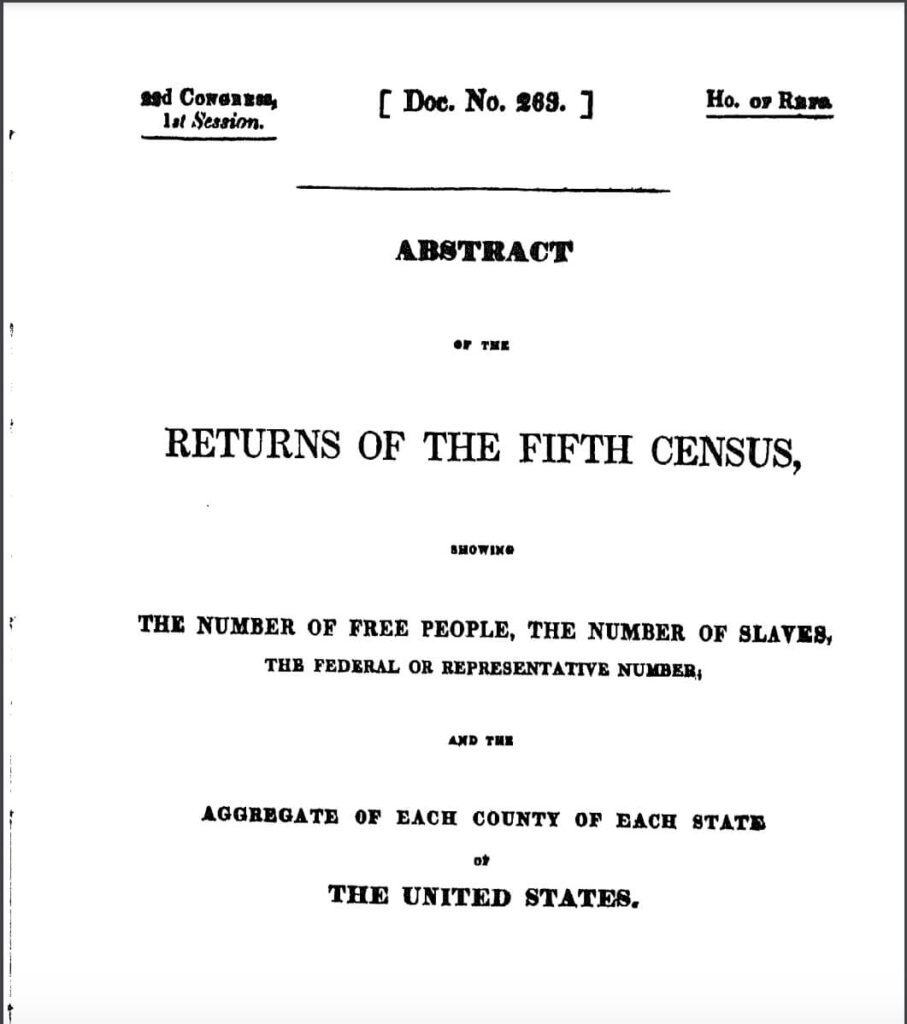

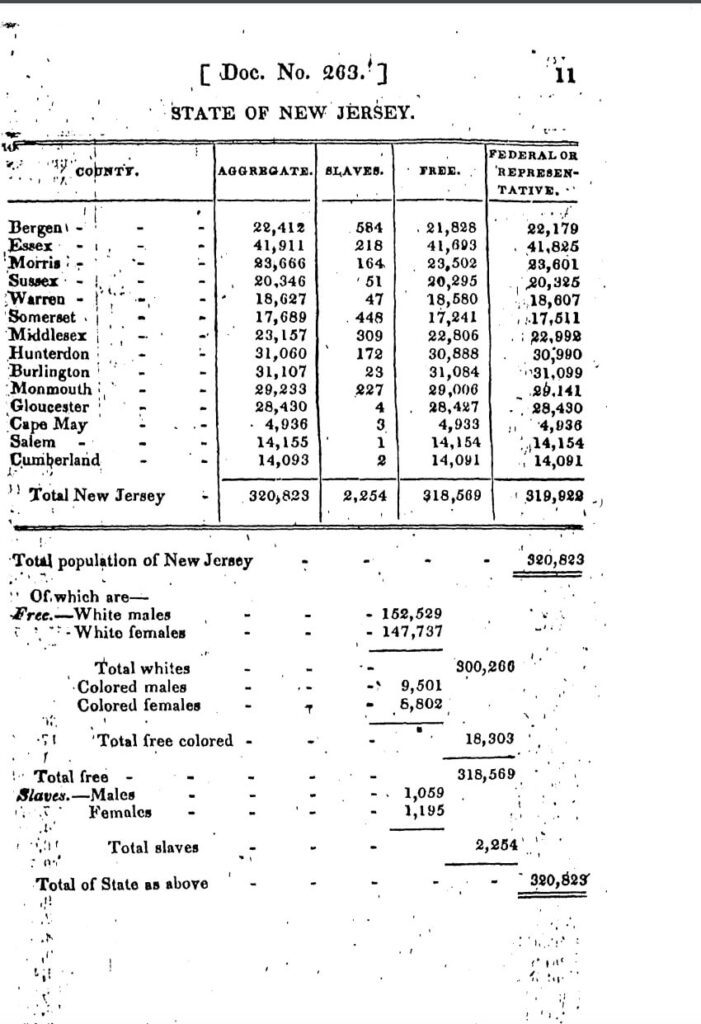

- All 16 Primary ResourcesThe Census of 1830

This abstract of the Census from 1830 not only provides numbers, state by state, of free and enslaved persons – but students will note that there are enslaved persons in many of the states they consider “free” (sample pages at left).

Note that the terminology is historically accurate but might be offensive to students unless context is provided (this will be true for many of the documents from this era).

CitePrintSharehttps://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1830/1830b.pdf

ORIIN, DUFF. “1830 Census - Full Document.” Census.gov, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1830/1830b.pdf.

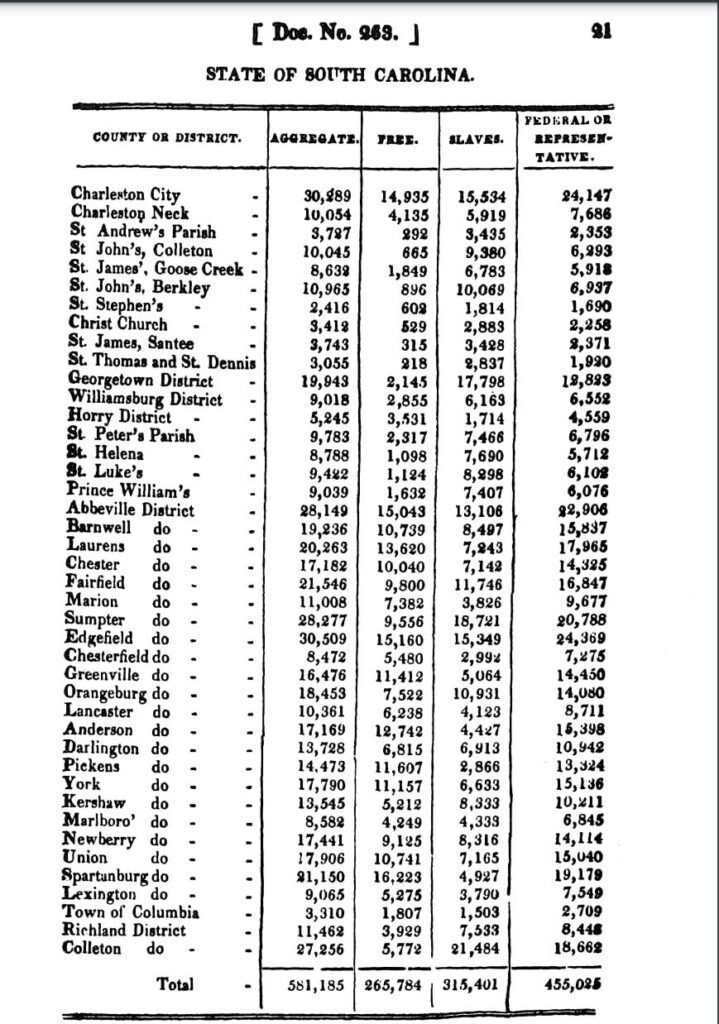

Nat Turner’s Rebellion, 1831Transcript“Even though Turner and his followers had been stopped, panic spread across the region. In the days following the attack, 3000 soldiers, militia men, and vigilantes killed more than one hundred suspected rebels. …Nat Turner’s rebellion led to the passage of a series of new laws. The Virginia legislature actually debated ending slavery, but chose instead to impose additional restrictions and harsher penalties on the activities of both enslaved and free African Americans. Other slave states followed suit, restricting the rights of free and enslaved blacks to gather in groups, travel, preach, and learn to read and write.” (Gilder Lehrman, link at right.)

Nat Turner’s Rebellion led to both public debate and a tightening of laws and policies. “Nat Turner was an enslaved man who had learned to read and write and become a religious leader despite his enslavement; following what he took to be religious signs, he led other enslaved people in an armed uprising. The violence of the uprising and Turner’s ability to escape and hide for approximately six weeks following the event led to changes in laws and policies and also led to a widespread climate of fear among white slaveholders. Enslaved people in far-flung states who had no connection to the event were lynched by white mobs. The State of Virginia briefly considered ending the practice of slavery in the wake of the rebellion, but they ultimately decided instead to tighten the laws of slavery.

1Africans in America/Part 3/Nat Turner's Rebellion. (n.d.). PBS. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part3/3p1518.html and Nat Turner - Rebellion, Death & Facts - HISTORY. (2021, January 26). History.com. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/nat-turnerCitePrintShareAllyn, Nelson. “Nat Turner's Rebellion, 1831 | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History |, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/nat-turner%E2%80%99s-rebellion-1831.

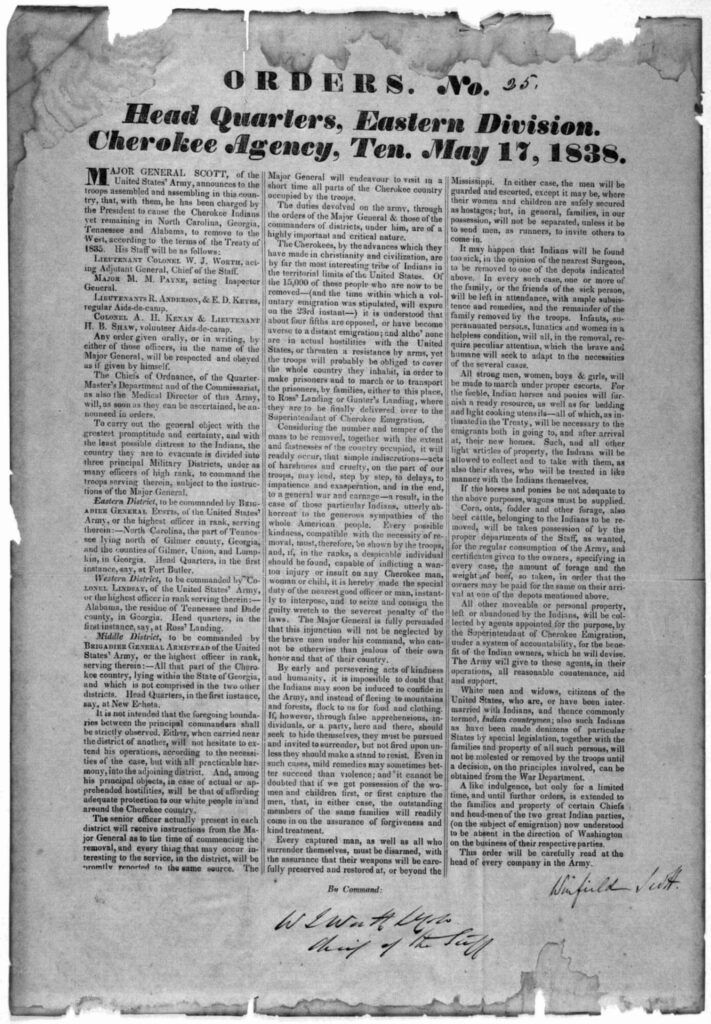

Orders pursuant to the Indian Removal Act of 1830 (Trail of Tears)Orders pursuant to the Indian Removal Act of 1830 (Trail of Tears)While the Trail of Tears and “Indian Removal Act” are not central to understanding slavery, they are critical events in the history of the country in this era; in addition, the concept of “indian removal” connects directly to tensions that rose as the nation expanded in both population and territory.

As the United States acquired Western territories, and as the power battle between slaveholding and free states continued, the land on which Native nations lived became increasingly valuable. After President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Choctaw, Creek, and Cherokee nations were forced to move from their land, most often on foot and with the deaths of many people, into Western territories. The 1838 forced removal of the Cherokee people from their Georgia land led to the deaths of thousands of people (exact numbers are unknown, but estimates range around 4,000 - 5,000.)

1- History & Culture - Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail (US National Park Service). (2020, July 10). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/trte/learn/historyculture/index.htm and Trail of Tears: Indian Removal Act, Facts & Significance - HISTORY. (2020, July 7). History.com. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/trail-of-tears

CitePrintShare“Tile.loc.gov.” Library of Congress, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/rbc/rbpe/rbpe17/rbpe174/1740400a/1740400a.pdf.

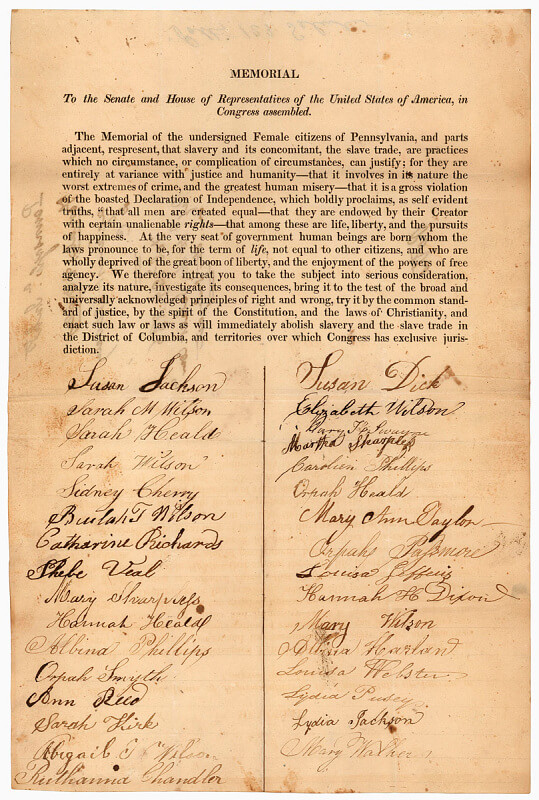

The Gag Rule, 1836“On May 26, 1836, the House of Representatives adopted a ‘Gag Rule’ stating that all petitions regarding slavery would be tabled without being read, referred, or printed….The enactment of the Gag Rule, rather than discouraging petitioners, energized the anti-slavery movement to flood the Capitol with written demands. Activists held up the suppression of debate as an example of the slaveholding South’s infringement of the rights of all Americans.”

CitePrintShareAdams, John Quincy. “The Gag Rule | National Museum of American History.” National Museum of American History, https://americanhistory.si.edu/democracy-exhibition/beyond-ballot/petitioning/gag-rule.

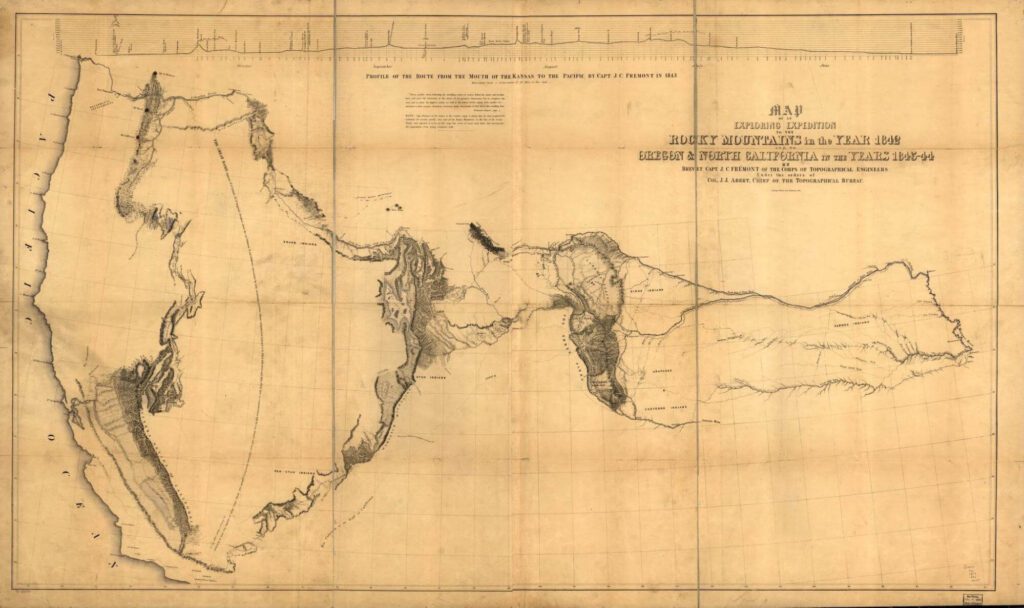

Map of Westward Expedition and Expansion, 1842-44Map of an exploring expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the year 1842 and to Oregon & north California in the years 1843-44As the nation expanded Westward, tensions rose further over whether new states and territories would permit or prohibit slavery.

CitePrintShareMap of an Exploring Expedition to the Rocky ... - Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4051s.ct000909/.

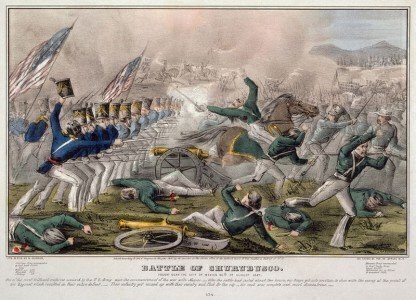

Battlefield Painting, Mexican-American WarBattlefield Painting, Mexican-American War“The pact set a border between Texas and Mexico and ceded California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming to the United States. …the acquisition of so much territory with the issue of slavery unresolved lit the fuse that eventually set off the Civil War in 1861.”

CitePrintShare“The Mexican-American war in a nutshell.” National Constitution Center, 13 May 2021, https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/the-mexican-american-war-in-a-nutshell.

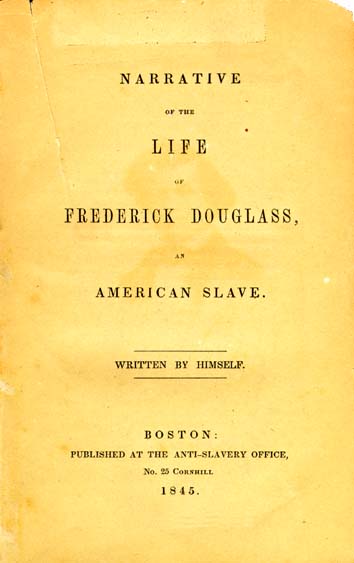

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, excerpt, 1845TranscriptCHAPTER I. I WAS born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about twelve miles from Easton, in Talbot county, Maryland. I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it. By far the larger part of the slaves know as little of their ages as horses know of theirs, and it is the wish of most masters within my knowledge to keep their slaves thus ignorant. I do not remember to have ever met a slave who could tell of his birthday. They seldom come nearer to it than planting-time, harvest-time, cherry-time, spring-time, or fall-time. A want of information concerning my own was a source of unhappiness to me even during childhood. The white children could tell their ages. I could not tell why I ought to be deprived of the same privilege. I was not allowed to make any inquiries of my master concerning it. He deemed all such inquiries on the part of a slave improper and impertinent, and evidence of a restless spirit. The nearest estimate I can give makes me now between twenty-seven and twenty-eight years of age. I come to this, from hearing my master say, some time during 1835, I was about seventeen years old.

Students would benefit from reading an excerpt of the text of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass – but in addition, the cover itself is an interesting artifact, and students can discuss its details and its possible impact upon publication in 1845. (See also text in this chart, below, from Frederick Douglass’ July 4 address in 1852.)

CitePrintShareHempel, Carlene, et al. “Frederick Douglass, 1818-1895. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself.” Documenting the American South, https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/douglass/douglass.html.

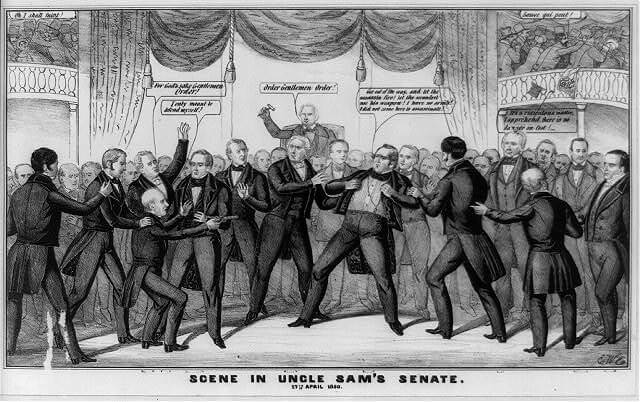

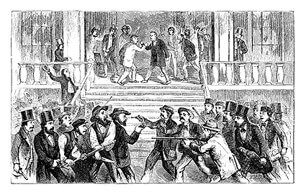

Scene in Uncle Sam’s Senate, 1850“Scene in Uncle Sam's Senate.Transcript"A somewhat tongue-in-cheek dramatization of the moment during the heated debate in the Senate over the admission of California as a free state when Mississippi senator Henry S. Foote drew a pistol on Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri.”

As new states were added to the nation, the question of how many would permit slavery and how many would prohibit it – and, therefore, which faction had more power – continued to contribute to growing tension.

CitePrintShare“Scene in Uncle Sam's Senate. 17th April 1850.” The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2008661528/.

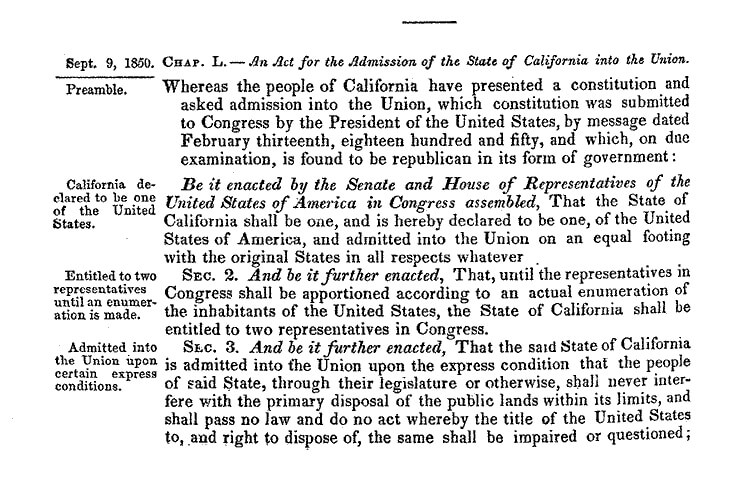

An Act for the Admission of the State of California into the Union, 1850CitePrintShareA Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875, https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=009%2Fllsl009.db&recNum=479.

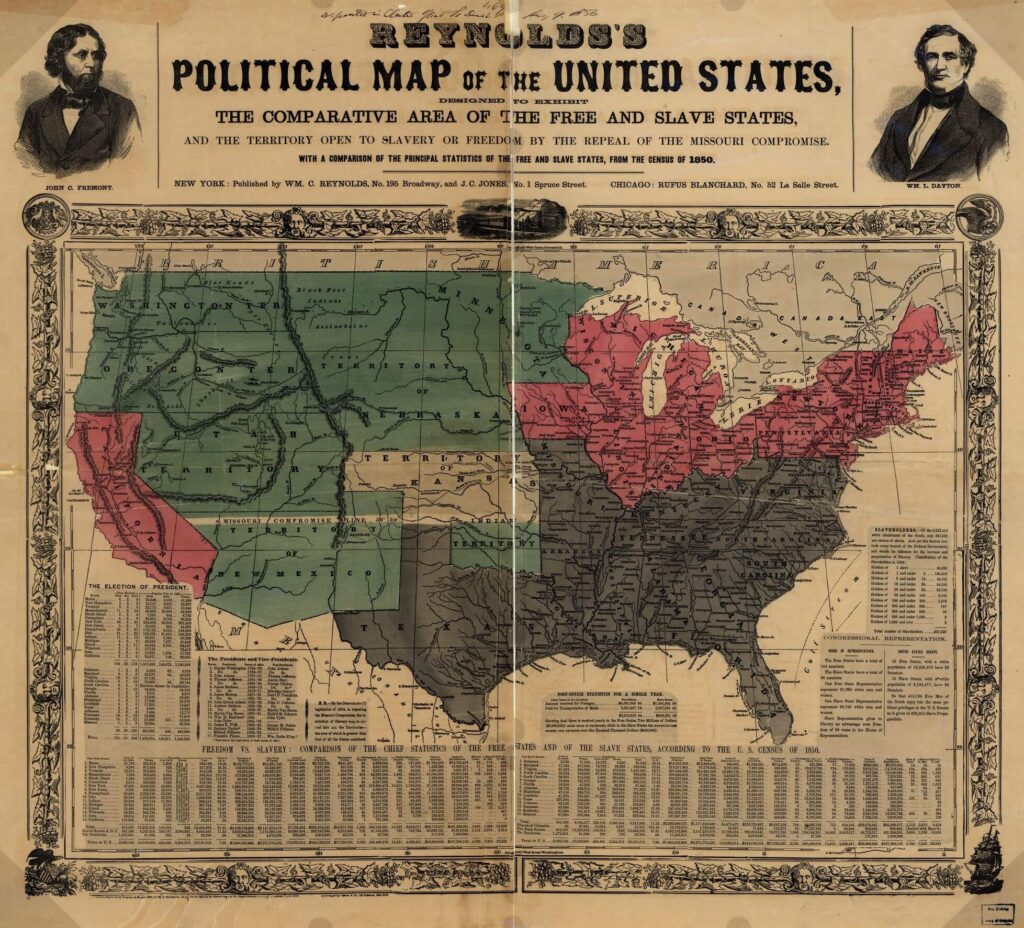

Political Map of the United States in 1850Political map of the United States in 1850This map has a range of valuable information, not only about Presidential politics, but also about population statistics and slavery. It makes a particular point of comparison with the 1830 Census, hyperlinked above in this chart.

CitePrintShare“1850 Political Map of the United States - History.” U.S. Census Bureau, 9 December 2021, https://www.census.gov/history/www/reference/maps/1850_political_map_of_the_united_states.html.

Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”, 1852Douglass raises critical questions about patriotism, citizenship, and the nation’s ideals in this address. The text highlights issues that will continue to be points of tension not only at the start of the Civil War, but throughout Reconstruction (and, truly, throughout American history).

“I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us. I am not included within the pale of glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

- Frederick Douglass, July 5, 1852CitePrintShareJuly 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass keynote address at an Independence Day celebration: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

“A Nation's Story: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”” National Museum of African American History and Culture, 3 July 2018, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/nations-story-what-slave-fourth-july.

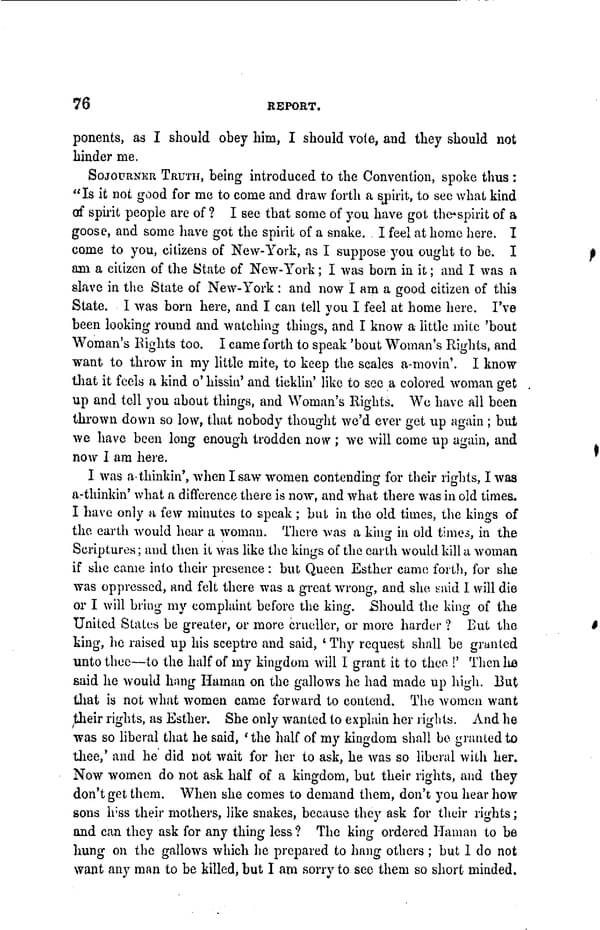

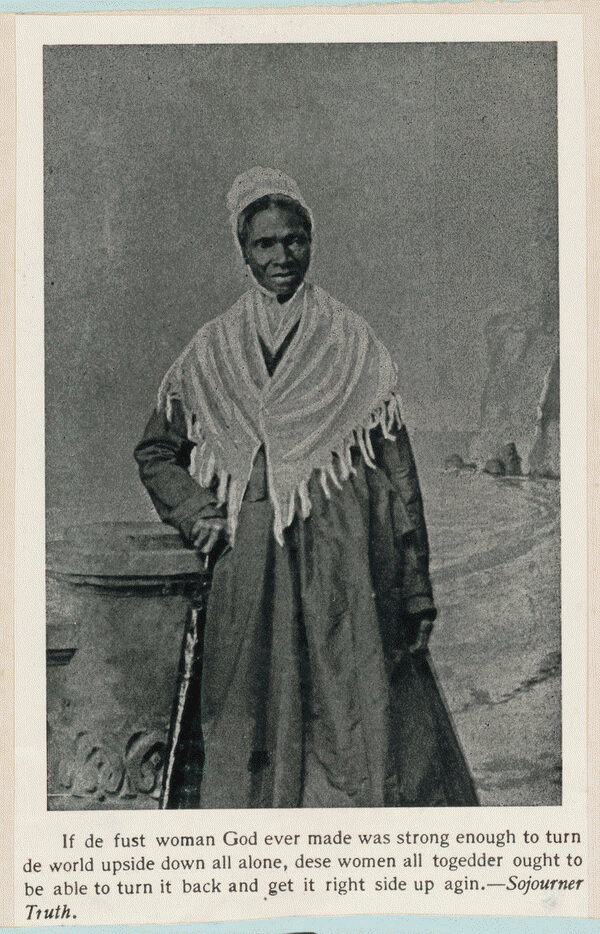

Sojourner Truth, Photograph and Speech at the Women’s Rights Convention, 1853See above; understanding the life and words of Sojourner Truth helps students to understand the complexity and intersectionality of both the women’s rights movement and the abolitionist movement.

CitePrintShareTitle Proceedings of the Woman's Rights Convention held at the Broadway Tabernacle, in the city of New York, on Tuesday and Wednesday, Sept. 6th and 7th, 1853.

Summary Sojourner Truth addresses the convention.

Image 76 of Susan B. Anthony Collection Copy | Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbnawsa.n8289/?sp=76.

“Bleeding Kansas,” 1858“The years of 1854-1861 were a turbulent time in Kansas territory. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 …allowed the residents of these territories to decide by popular vote whether their state would be free or slave. This concept of self-determination was called popular sovereignty'. …Three distinct political groups occupied Kansas: pro-slavers, free-staters and abolitionists. Violence broke out immediately between these opposing factions and continued until 1861 when Kansas entered the Union as a free state on January 29th. This era became forever known as ‘Bleeding Kansas’.” (National Park Service, link at right.)

CitePrintShare“Bleeding Kansas - Fort Scott National Historic Site (US National Park Service).” National Park Service, 23 April 2020, https://www.nps.gov/fosc/learn/historyculture/bleeding.htm.

Abraham Lincoln, “A House Divided” Speech, 1858This excerpt from (or the entirety of) Lincoln’s address to the Republican State Convention puts the notion of “a house divided” in its original context, just before the start of the Civil War.

NOTE: Because it provides the central concept of this set of resources, I’ve included it last (although it predates John Brown’s speech above.)

Illinois Republican State Convention, Springfield, Illinois June 16, 1858Abraham Lincoln

Mr. President and Gentlemen of the Convention. If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do, and how to do it.

We are now far into the fifth year, since a policy was initiated, with the avowed object, and confident promise, of putting an end to slavery agitation. Under the operation of that policy, that agitation has not only, not ceased, but has constantly augmented.

In my opinion, it will not cease, until a crisis shall have been reached, and passed -

"A house divided against itself cannot stand."

I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.

I do not expect the Union to be dissolved - I do not expect the house to fall - but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.

1- John Brown's Raid (US National Park Service). (2021, July 30). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/articles/john-browns-raid.htm

- John Brown's Raid on Harper's Ferry. (n.d.). Ohio History Central. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/John_Brown%27s_Raid_on_Harper%27s_Ferry

CitePrintShare“House Divided Speech - Lincoln Home National Historic Site (US National Park Service).” National Park Service, 10 April 2015, https://www.nps.gov/liho/learn/historyculture/housedivided.htm.

An excerpt from John Brown's address to the court after hearing his guilty verdict, 1859John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry fits into Lincoln’s foretelling of a crisis and further spurs the start of the Civil War. Brown’s speech to the courtroom highlights his sense of what, in this moment, constitutes justice and injustice.

John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry: John Brown, an abolitionist, led the Raid on Harper’s Ferry, a federal arsenal, in an effort to start an armed insurrection against slavery. The event, which took place after Lincoln’s “a house divided” speech, serves as an example of the violence Lincoln foretold. Brown echoed Lincoln’s sentiments, explaining in 1859, “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.” Brown and his followers were trapped and arrested, and Brown was tried and found guilty of treason.

“I have, may it please the court, a few words to say. In the first place, I deny everything but what I have all along admitted--the design on my part to free the slaves. I intended certainly to have made a clean thing of that matter, as I did last winter when I went into Missouri and there took slaves without the snapping of a gun on either side, moved them through the country, and finally left them in Canada. I designed to have done the same thing again on a larger scale. That was all I intended. I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.I have another objection; and that is, it is unjust that I should suffer such a penalty. Had I interfered in the manner which I admit...had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends--either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class--and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.”

CitePrintShare“An excerpt from John Brown's address to the court after hearing his guilty verdict, 1859.” Digital Public Library of America, https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/john-brown-s-raid-on-harper-s-ferry/sources/1722.

The Women’s Rights Convention of 1853TranscriptQuotation beneath the photograph: "If de fust woman God ever made was strong enough to turn de world upside down all alone, dese women all togedder ought to be able to turn it back and get it right side up agin."

This photograph pairs with the text in the row below from the Women’s Rights Convention of 1853, when Sojourner Truth spoke to the group.

The Women’s Rights Convention: The Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 is a significant event in the fight for women’s rights and for women’s suffrage, though activists at the convention itself debated whether suffrage should be the center point of their platform. In addition, the Seneca Falls Convention is now widely understood to represent some tension between the women’s rights movement and the abolitionist movement; some activists at the time felt that the right to vote should not go to black men before white women. In this collection of documents, Sojourner Truth’s speech to a smaller, subsequent convention – one held in New York in 1853 – is included, largely because of the critical role Sojourner Truth plays in demonstrating the importance of the intersectionality of both the women’s rights and abolitionist movements.

1- On this day, the Seneca Falls Convention begins. (2021, July 19). National Constitution Center. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/on-this-day-the-seneca-falls-convention-begins and More Women's Rights Conventions - Women's Rights National Historical Park (US National Park Service). (n.d.). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/more-womens-rights-conventions.htm and Proceedings of the Woman's Rights Convention held at the Broadway Tabernacle, in the city of New York, on Tuesday and Wednesday, Sept. 6th and 7th, 1853. (n.d.). Library of Congress. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.loc.gov/item/93838289/

CitePrintShare“Sojourner Truth.” The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/rbcmiller001306/.

Education for American Democracy

This resource set contains best practices for teaching about Native people in your classroom and sample maps with Native viewpoints and inquiry questions to use in your classroom.

The Roadmap

Norman B. Leventhal Map & Education Center

In the decades following the Civil War, the US military clashed with Native Americans in the West. The Battle of Little Bighorn was one of the Native Americans' most famous victories. In this lesson, students explore causes of the battle by comparing two primary documents with a textbook account.

The Roadmap

Stanford History Education Group

This 12-lesson teacher's guide accompanies the Emmy-award winning documentary film, DAWNLAND, about the forced removal and coerced assimilation of Indigenous children and the first truth and reconciliation commission in U.S. history to focus on issues of importance to Indigenous Peoples. The compelling question of the guide is: What is the relationship between the taking of the land and the taking of the children?

The Roadmap

Upstander Project

In this lesson, students will select 25 environmental laws in American history from a larger list to produce their own timeline of American environmental law history to present to the rest of the class.

The Roadmap

American Bar Association

Students explore themes of social justice and fair access through a simulation activity, creating new rules for settlement of a new planet Earth. They debrief the activity using John Rawls's concept of the ‘Veil of Ignorance.’ Students define social justice in terms of fair access and create their own vision of what a just future looks like.

The Roadmap

High Resolves

The Coronavirus Pandemic of 2020 has increased public awareness of the field of public health, which takes as its key goals “protecting and improving the health of people and their communities”(according to the CDC). In part because public health is so little understood or discussed in the U.S., government interventions to respond to the pandemic, including efforts to encourage masking and vaccinations, met with significant controversy and a wide variety of responses on the state and local levels. But the notion of government response to public health crises was not new in 2020; indeed, American public health measures including quarantine and inoculation predate the founding of the United States.

This Spotlight Kit covers a range of historic events in the realm of public health, including (but not limited to) Yellow Fever in 1793, public health crises of the Civil War, the 1918 flu epidemic, and the development of the polio vaccine in 1955. The documents herein reveal perennial questions about what the responsibility of the government is to its citizens’ health and what the limitations are to the public will for government intervention.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by Era/DateEighteenth Century (4)Nineteenth Century (5)Early Twentieth Century (including 1918 Flu Pandemic) (4)Later Twentieth Century (5)

- All 18 Primary ResourcesFrom George Washington to William Shippen, Jr. (1777)

During the Revolutionary War, according to military historians, approximately 90% of deaths among soldiers were the result of the spread of smallpox. As a result, Washington decided to mandate the vaccination of the troops – a process more dangerous and complicated in that era than our public vaccination campaigns today.

CitePrintShare“From George Washington to William Shippen, Jr., 6 February 1777,” Founders Online, National Archives, https://founders.archives.gov/documents/Washington/03-08-02-0281. [Original source: The Papers of George Washington, Revolutionary War Series, vol. 8, 6 January 1777 – 27 March 1777, ed. Frank E. Grizzard, Jr. Charlottesville: University Press of Virginia, 1998, p. 264.]

Thomas Jefferson to James Madison (1793)TranscriptThomas Jefferson to James Madison, 1793: “I think there is rational danger, but that I had before announced that I should not go till the beginning of October, & I do not like to exhibit the appearance of panic. Besides that I think there might serious ills proceed from there being not a single member of the administration in place. Poor Hutcheson dined with me on Friday was sennight, was taken that night on his return home, & died the day before yesterday.”

In this letter, Thomas Jefferson describes how the yellow fever is harming countless people, even those in the government, yet no one seems to know what can be done. Alexander Hamilton is ill, others are sick or dying, and Jefferson writes about avoiding the appearance of “panic” for the public.

1The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use. Teachers, if your use will be beyond a single classroom, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.CitePrintShareThomas Jefferson to James Madison, September 8, with Fragment Copy. -09-08, 1793. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, accessed from the Library of Congress on March 27, 2022, at www.loc.gov/item/mtjbib007979/.

Note: If you select to download the PDF below the image, you can see a transcript of the letter.

A Narrative of the Proceedings of the Black People, during the Late Awful Calamity in Philadelphia, in the Year 1793TranscriptA narrative of the proceedings of the black people, during the late awful calamity in Philadelphia, in the year 1793:

“We feel ourselves sensibly aggrieved by the censorious epithets of many, who did not render the least assistance in the time of necessity, yet are liberal of their censure of us, for the prices paid for our services, when no one knew how to make a proposal to any one they wanted to assist them. At first we made no charge but left it to those we served in removing their dead, to give what they thought fit–we set no price, until the reward was fixed by those we had served. After paying the people we had to assist us, our compensation is much less than many will believe.” (pp. 7-8)

This primary source reflects the incredible help that African Americans provided during Philadelphia’s yellow fever epidemic of 1793. Those who helped recount speaking with the mayor about what could be done and working with the government of the city in order to help those in need. Later in the document, the writers recount that they asked for pay for their many services given during this time of illness and need, yet some citizens turned against them.

CitePrintShareJones, Absalom, et al. A narrative of the proceedings of the black people, during the late awful calamity in Philadelphia, in the year: and a refutation of some censures thrown upon them in some late publications. Philadelphia: Printed for the authors, by William W. Woodward, 1794. Pdf. Accessed March 27, 2022 from the Library of Congress at www.loc.gov/item/02013737/

Note: This is a 32 page primary source document in its original form. If you wish to access a transcript of portions of this document in Microsoft Word form, that can be accessed from the Texas State University Library Guides; the citation for this is as follows:

Absolom Jones and Richard Allen, “On Black Philadelphians’ Conduct During the Yellow Fever Epidemic of 1793-1794,” ExplorePAhistory.com, accessed March 27, 2022 fro the Texas State University Library Guides at https://explorepahistory.com/odocument.php?docId=1-4-169.

“Account of the yellow fever outbreak in Philadelphia, October 11-14, 1793” (1793)“Account of the yellow fever outbreak in Philadelphia, October 11-14, 1793”TranscriptPhiladelphia 11th october 1793 11 OClock A.M. “The fever from all that I can learn is more fatal than ever, yesterday a vast number of burials – I do not expect any abatement of the fever before we have rain and high winds – The day before yesterday we were witness to what appears to me Shocking – a Coffin was brought to the entrance of Welsh’s alley, where it stayed sometime for the man to die before he was put into the Coffin, Such hurry must bury many alive.”

New York 14th October 1793 ½ past 10 OClock A.M. “The mail is arrived, I have no letters but I have seen Several, The malady in Philada continues dreadful, one hundred and thirty Seven were buried on friday last by the Committee independent of many who were buried by their friends, Fifty eight were Carried from Bush hill to Pottersfield Thursday last.—”

The federal government left Philadelphia in 1793 to avoid the yellow fever epidemic; the federal government’s response to the health concern was to leave the city. This letter is from Secretary of War Henry Knox and relates to the government weighing whether or not it was safe for them to go back to Philadelphia (students may need to be reminded that before Washington, DC, the federal government met in Philadelphia).

CitePrintShare“Account of the yellow fever outbreak in Philadelphia, October 11-14, 1793”, from the Gilder Lehrman Collection. Accessed on March 27, 2022 from https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/reports-yellow-fever-epidemic-1793

Note: A transcript of this letter is also available from this same page cited above.

The Shattuck Report (1850)Known as the Shattuck Report and done with the Massachusetts Sanitary Commission in 1850, this was the first in-depth look at public health. It focused on health and living conditions in Boston but had far-reaching impacts in bringing public health to the forefront of important national issues. According to many, this was the first attempt to get a public health code in place in a major American city. Shattuck’s report came at a time when the government was doing little to help immigrants arriving to the US, low-wage workers were living in unsanitary conditions, the working poor received almost no government help, and healthcare was nearly nonexistent for those living in poverty. The report revealed the need for public health codes and government intervention; according to LSU Biotech Law, “This report is one of the fundamental documents in public health in the United States. It is the first systematic use of birth and death records and other demographic data to describe the health of a population. Its recommendations became the foundation of the sanitation movement in the United States. . . “ This report also outlines technology as a necessity for government intervention in public health, mentioning everything from sanitation systems to sanitation laws.

CitePrintShareHistoric Public Health Books: “The Shattuck Report: LEMUEL SHATTUCK - REPORT OF A GENERAL PLAN FOR THE PROMOTION OF GENERAL AND PUBLIC HEALTH DEVISED, PREPARED AND RECOMMENDED BY THE COMMISSIONERS APPOINTED UNDER A RESOLVE OF THE LEGISLATURE OF MASSACHUSETTS, RELATING TO A SANITARY SURVEY OF THE STATE. (1850)”; accessed from LSU Biotech Law on March 27, 2022 at https://biotech.law.lsu.edu/cphl/history/books/sr/

Note: This is a transcript of the entire book by Lemuel Shattuck. From this link provided above, you can select to view any page on the original primary source book from 1850.

“Rules for preserving the health of the soldier” (1861)“Rules for preserving the health of the soldier” (1861)Transcript“To secure by all possible means the health and efficiency of our troops now in the field, and to prevent unnecessary disease and suffering. . .. Every officer and soldier should be carefully vaccinated with fresh vaccine matter, unless already marked by small-pox.”

This book outlines health advice for soldiers; it was published by the federal government under the US Sanitary Commission during the Civil War, at a time when the Union Army needed government assistance to keep soldiers healthy. The work also discusses everything from diet to sanitation.

CitePrintShare“Rules for preserving the health of the soldier”, provided by the U.S. National Library of Medicine Digital Collections; accessed March 27, 2022, from https://collections.nlm.nih.gov/bookviewer?PID=nlm:nlmuid-101201682-bk.

If you wish to read a transcript of portions of this work, you can use the following source:

Teach US History.org, “Rules for Preserving the Health of the Soldier”, accessed March 27, 2022 at https://www.teachushistory.org/civil-war/resources/rules-preserving-health-soldier#:~:text=Every%20officer%20and%20soldier%20should,the%20exigencies%20of%20service%20permit.

Union field hospital after the battle of June 27 (1862)This photograph shows a Union Civil War hospital in June 1862. This photograph could be used in conjunction with the “Rules for the preserving the health of the soldier” (the primary source listed above) to showcase some of the measures taken for the health of soldiers.

CitePrintShareGibson, James F, photographer. Savage Station, Virginia. Union field hospital after the battle of June 27. June. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, www.loc.gov/item/2018671740/.

Letter from Dr. John H. Rapier, Jr. to his uncle (1864)Transcript“I drew $100 less war tax $2.50 for Medical Services rendered the U.S. Government. … I must tell you coloured men in the U.S. Uniform are much respected here, and in visiting the various Departments if the dress is that of an Officer, you receive the military salute from the ground as promptly as if your blood was a Howard or Plantagenent instead of a Pompey or Cuffee’s. … I had decided not to wear the uniform but I have altered my mind—and I shall appear hereafter in full dress gold lace, pointed hat, straps and all. Mr. Fred Douglass spoke here last night to an immense audience and today the President sent for him to visit him in the Capitol.”

This four-page August 19, 1864 letter is from African American surgeon Dr. John H. Rapier, Jr. In the letter, Dr. Rapier recounts being paid by the US government for his medical services. This primary source shows the important role of African American medical practitioners in the Civil War, and makes reference to Frederick Douglass being summoned by the President and meeting with Dr. Rapier thereafter.

CitePrintShareLetter from Dr. John H. Rapier, Jr. to his uncle James P. Thomas, Esq., St. Louis, Missouri, from Freedmen's Hospital, Washington, D.C., August 19, 1864 (transcript available). Courtesy Moorland-Spingarn Research Center, Howard University. Accessed March 27, 2022 from the NIH US National Library of Medicine at https://www.nlm.nih.gov/exhibition/bindingwounds/education/onlineactivities.html

Hygienic Laboratory at the Marine Hospital, Staten Island, New York (1887-1891)These photographs are from the Marine Hospital at Staten Island, New York, where the Hygienic Laboratory was established in 1887. The tents are for people with tuberculosis; Joseph James Kinyoun was the Assistant Surgeon at this location and urged isolation as a way to combat tuberculosis. According to the NIH, this Marine Hospital “marked the beginning of the National Institutes of Health and laid the groundwork for government-supported scientific research in the United States”. A major purpose of this location was to look for diseases among immigrants arriving from Europe, at a time when anti-immigrant beliefs were already a problem in the US.

CitePrintShareNational Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIH), “The Hygienic Laboratory - Abutment”, access from the NIH on March 27, 2022 at https://www.niaid.nih.gov/about/joseph-kinyoun-indispensable-man-hygienic-laboratory

Photographs from Ellis Island (1907)Physicians examining a group of Jewish immigrants (1907)Immigrants just arrived, awaiting examination, Ellis Island, New York harbor (1907)This 1907 photograph shows immigrants being examined at Ellis Island. The US government required medical examinations upon arrival in the US. It could be important to point out public perceptions of immigrants at this time in American history, and how anti-immigrant beliefs were influencing government decisions about medicine and health.

CitePrintShareUnderwood & Underwood, Copyright Claimant. Physicians examining a group of Jewish immigrants. Photograph. Access March 27, 2022 from the Library of Congress at www.loc.gov/item/2012646350/

Underwood & Underwood. Immigrants just arrived, awaiting examination, Ellis Island, New York harbor. [London: underwood & underwood, european publishers, ltd., between 1870 and 1920] Photograph. Accessed March 27, 2022 from the Library of Congress at www.loc.gov/item/2017660810/

Birmingham, Alabama Board of Education School Board Minutes (1918)In terms of government public health initiatives over time, local governments are an important part of that history. This primary source is from Birmingham, Alabama’s School Board minutes from December 1918, in which the possibility of closing schools due to the flu epidemic. The document explains that doctors of the Committee of Health have been consulted on the issue as well. This could be a useful primary source for studying local government decisions in public health issues.

CitePrintShareBirmingham, Alabama Board of Education December 3, 1918 School Board Minutes. Published: Ann Arbor, Michigan: Michigan Publishing, University Library, University of Michigan. Courtesy of: Department of Archives and Manuscripts, Birmingham Public Library, Birmingham, AL. Accessed March 29, 2022 from the Influenza Encyclopedia, from the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing, University of Michigan Library Influenza Archive, at

“Swat the Flu…”: The Bismarck Tribune (1919)This 1919 newspaper article has the headline “Swat the Flu is Slogan for 1919 Campaign Against Dread Destroyer that Looms Again: Measure Approved in Both Houses of Congress Would Appropriate $5,000,000 for Investigation of Epidemic Which Swept Over America in 1918, Costing Thousands of Lives”. The article details government actions regarding public health during the 1918-1919 flu epidemic.

CitePrintShareThe Bismarck tribune. [volume] (Bismarck, N.D.), 29 July 1919. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. Accessed March 29, 2022 from the Library of Congress at https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn85042243/1919-07-29/ed-1/seq-1/

President Coolidge, Address at the Annual Session of the American Medical Association (1927)This address, given by President Coolidge to the American Medical Association, speaks broadly to the role of the field of public health and the trust he feels society must place in science and medicine.

President Calvin Coolidge, Address at the Annual Session of the American Medical Association, Washington, D.C., May 17, 1927

Ladies and Gentlemen:“...Those who have witnessed the general paralysis which prevails when even a moderate epidemic breaks out can not help but realize that one of the most important factors of our everyday existence is the public health, which has come to be dependent upon sanitation and the medical profession. We are constantly in receipt of the beneficial activities of these efforts in the disposition of waste, the water we drink, the food we eat, and even in the air we breathe. This great work is carried on partly through private initiative, partly through Government effort, partly by a combination of these two working in harmony with the science of chemistry, of engineering, and of applied medicine. In its main aspects it is preventive, but in a very large field it is remedial. Without this service our large centers of population would be overwhelmed and dissipated almost in a day and the modern organization of society would be altogether destroyed. The debt which we owe to the science of medicine is simply beyond computation or comprehension….

If there is any one thing which the progress of science has taught us, it is the necessity of an open mind. Without this attitude very little advance could be made. Truth must always be able to demonstrate itself. But when it has been demonstrated, in whatsoever direction it may lead, it ought to be followed.”

CitePrintShare“Address at the Annual Session of the American Medical Association, Washington, D.C. | The American.” The American Presidency Project, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/address-the-annual-session-the-american-medical-association-washington-dc.

The Polio Vaccine Assistance Act of 1955This 1955 primary source is about the US government’s Polio Vaccine Assistance Act and the US government’s public health efforts to fight polio. This two-page document explains how states will receive money for vaccination programs and distribute the vaccine, among other details. Notice the first page calls this a “new advance in preventive medicine”.

CitePrintShareAJPH: A Publication of the American Public Health Association, Otis L. Anderson, MD, F.A.P.H.A, “The Polio Vaccine Assistance Act of 1955”, October 1955. Accessed March 27, 2022 from the AJPH at https://ajph.aphapublications.org/doi/pdf/10.2105/AJPH.45.10.1349#:~:text=The%20Polio%20Vaccine%20Assistance%20Act%20of%201955%2C%20passed%20by%20the,of%20planning%20and%20conducting%20vaccination

White House Press Release on the Salk Polio Vaccine (1955)This 1955 White House press release details President Eisenhower’s honoring Jonas Salk with a “citation for his extraordinary achievement” in developing a polio vaccine. Eisenhower, in this press release, details the massive efforts the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis has taken to work towards a polio vaccine. President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s own struggle with polio, and the gratitude of America as a whole, are also discussed.

CitePrintShareWhite House press release with text of citations given by the President to Dr. Jonas E. Salk and the National Foundation for Infantile Paralysis, April 22, 1955 [DDE's Records as President, Official File, Box 511, 117-I-1 Salk Polio Vaccine (8); NAID #12166355]. Accessed March 29, 2022 from the Dwight D. Eisenhower Presidential Library at https://www.eisenhowerlibrary.gov/sites/default/files/research/online-documents/salk/salk-c.pdf

Public Health Video (1955)This Library of Congress 14 minute and 35 second video is from 1955 and details the efforts made to fight polio. From the NBC Television Collection, this primary source allows students to watch a primary source video that details items such as how vaccines are made, including the safety of vaccines. The description reads: “HEW Secretary Oveta Culp Hobby and Surgeon General Leonard Scheele talk about the Salk polio vaccine and assuage concerns about its safety”. (HEW is “Health, Education, and Welfare”.)

CitePrintShareScheele, Leonard Andrew, et al. A Special Report on Polio. 1955. Video. Accessed March 29, 2022 from the Library of Congress at www.loc.gov/item/mbrs00056792/

Special Message to the Congress on the Nation's Health (1964)This address to Congress delineates a public health agenda that includes numerous measures for increasing both the national and international commitments to health infrastructure and access. In doing so, it connects issues of public health and access to health care to President Johnson’s War on Poverty.

President Lyndon B. Johnson, Special Message to the Congress on the Nation's Health (1964)

To the Congress of the United States:The American people are not satisfied with better-than-average health. As a Nation, they want, they need, and they can afford the best of health:

--not just for those of comfortable means.

--but for all our citizens, old and young, rich and poor.

In America,

--There is no need and no room for second-class health services.

...Too many Americans still are cut off by low incomes from adequate health services. Too many older people are still deprived of hope and dignity by prolonged and costly illness. The linkage between ill-health and poverty in America is still all too plain.

In its first session, the 88th Congress made some important advances on the health front:

--It acted to increase our supply of physicians and dentists.

--It began a Nation-wide attack on mental illness and mental retardation.

--And it strengthened our efforts against air pollution.

But our remaining agenda is long, and it will be unfinished until each American enjoys the full benefits of modern medical knowledge.

Part of this agenda concerns a direct attack on that particular companion of poor health--poverty. Above all, we must see to it that all of our children, whatever the economic condition of their parents, can start life with sound minds and bodies.

My message to the Congress on poverty will set forth measures designed to advance us toward this goal.

In today's message, I present the rest of this year's agenda for America's good health.

CitePrintShareJohnson, Lyndon B. “Special Message to the Congress on the Nation's Health.” The American Presidency Project, 10 February 1964, https://www.presidency.ucsb.edu/documents/special-message-the-congress-the-nations-health.

Surgeon General's Report on Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (1987)The Reagan Administration was slow to respond to the initial emergence and spread of AIDS (Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome). Political activism, both within and outside of the LGBTQ community, pushed for more government support, resources, and attention to the disease and its victims. As a National Library of Medicine profile of Surgeon General C. Everett Koop explains, “ In 1986, he was finally authorized to issue a Surgeon General's report on AIDS. In 1988, he mailed a congressionally-mandated information brochure on AIDS to every American household.”

- Everett Koop, Surgeon General's Report on Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndrome (1987):

“Every person can reduce the risk of exposure to the AIDS virus through preventive measures that are simple, straightforward, and effective. However, if people are to follow these recommended measures-to act responsibly to protect themselves and others-they must be informed about them. That is an obvious statement, but not a simple one. Educating people about AIDS has never been easy.

From the start, this disease has evoked highly emotional and often irrational responses. Much of the reaction could be attributed to fear of the many unknowns surrounding a new and very deadly disease. This fear was compounded by personal feelings regarding the groups of people primarily affected-homosexual men and intravenous drug abusers. Rumors and misinformation spread rampantly and became as difficult to combat as the disease itself. It is time to put self-defeating attitudes aside and recognize that we are fighting a disease-not people. We must control the spread of AIDS, and at the same time offer the best we can to care for those who are sick.”

CitePrintShareKoop, CE. “Surgeon General's report on acquired immune deficiency syndrome.” NCBI, 1987, https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/articles/PMC1477712/.

Education for American Democracy

This free curriculum guide from the New-York Historical Society examines the evolution of environmental thinking through the lens of the Hudson River, spanning two centuries of industrial development, activism, and artistic imagination.

The Roadmap

New-York Historical Society

Hurricane Katrina made landfall on the Gulf Coast on August 29, 2005, killing hundreds of people and causing billions of dollars in damage. The effects of the storm are still felt today in Louisiana and Mississippi, and the government response to the storm remains a politically charged issue. In this lesson, students learn about the storm and consider whether a range of online sources provide reliable information about the effects of Hurricane Katrina.

The Roadmap

Stanford History Education Group

Mapping Inequality introduces the viewer to the records of the Home Owners' Loan Corporation (HOLC) on a scale that is unprecedented. Here you can browse more than 150 interactive maps and thousands of "area descriptions." These materials afford an extraordinary view of the contours of wealth and racial inequality in Depression-era American cities and insights into discriminatory policies and practices that so profoundly shaped cities that we feel their legacy to this day.

The Roadmap

New American History

This six-lesson unit is designed to launch a course on US history, literature, or civic life through an examination of students’ individual identities. Students are empowered to develop their own voices in both the classroom and the world at large and to recognize that their voices are integral to the story of the country.

The Roadmap

Facing History and Ourselves

In this learning resource, students use geospatial technology to understand how Native land changed hands from the start of European colonization to the contemporary moment. Students will understand the impact settler colonialism has on Indigenous people and their homes and the changes of population that resulted from westward expansion.

The Roadmap

Esri

Download the Roadmap and Report

Download the Educating for American Democracy Roadmap and Report Documents

Get the Roadmap and Report to unlock the work of over 300 leading scholars, educators, practitioners, and others who spent thousands of hours preparing this robust framework and guiding principles. The time is now to prioritize history and civics.

Your contact information will not be shared, and only used to send additional updates and materials from Educating for American Democracy, from which you can unsubscribe.

We the People

This theme explores the idea of “the people” as a political concept–not just a group of people who share a landscape but a group of people who share political ideals and institutions.

Institutional & Social Transformation

This theme explores how social arrangements and conflicts have combined with political institutions to shape American life from the earliest colonial period to the present, investigates which moments of change have most defined the country, and builds understanding of how American political institutions and society changes.

Contemporary Debates & Possibilities

This theme explores the contemporary terrain of civic participation and civic agency, investigating how historical narratives shape current political arguments, how values and information shape policy arguments, and how the American people continues to renew or remake itself in pursuit of fulfillment of the promise of constitutional democracy.

Civic Participation

This theme explores the relationship between self-government and civic participation, drawing on the discipline of history to explore how citizens’ active engagement has mattered for American society and on the discipline of civics to explore the principles, values, habits, and skills that support productive engagement in a healthy, resilient constitutional democracy. This theme focuses attention on the overarching goal of engaging young people as civic participants and preparing them to assume that role successfully.

Our Changing landscapes

This theme begins from the recognition that American civic experience is tied to a particular place, and explores the history of how the United States has come to develop the physical and geographical shape it has, the complex experiences of harm and benefit which that history has delivered to different portions of the American population, and the civics questions of how political communities form in the first place, become connected to specific places, and develop membership rules. The theme also takes up the question of our contemporary responsibility to the natural world.

A New Government & Constitution

This theme explores the institutional history of the United States as well as the theoretical underpinnings of constitutional design.

A People in the World

This theme explores the place of the U.S. and the American people in a global context, investigating key historical events in international affairs,and building understanding of the principles, values, and laws at stake in debates about America’s role in the world.

The Seven Themes

The Seven Themes provide the organizational framework for the Roadmap. They map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. Importantly, they are neither standards nor curriculum, but rather a starting point for the design of standards, curricula, resources, and lessons.

Driving questions provide a glimpse into the types of inquiries that teachers can write and develop in support of in-depth civic learning. Think of them as a starting point in your curricular design.

Learn more about inquiry-based learning in the Pedagogy Companion.

Sample guiding questions are designed to foster classroom discussion, and can be starting points for one or multiple lessons. It is important to note that the sample guiding questions provided in the Roadmap are NOT an exhaustive list of questions. There are many other great topics and questions that can be explored.

Learn more about inquiry-based learning in the Pedagogy Companion.

The Seven Themes

The Seven Themes provide the organizational framework for the Roadmap. They map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. Importantly, they are neither standards nor curriculum, but rather a starting point for the design of standards, curricula, resources, and lessons.

The Five Design Challenges

America’s constitutional politics are rife with tensions and complexities. Our Design Challenges, which are arranged alongside our Themes, identify and clarify the most significant tensions that writers of standards, curricula, texts, lessons, and assessments will grapple with. In proactively recognizing and acknowledging these challenges, educators will help students better understand the complicated issues that arise in American history and civics.

Motivating Agency, Sustaining the Republic

- How can we help students understand the full context for their roles as civic participants without creating paralysis or a sense of the insignificance of their own agency in relation to the magnitude of our society, the globe, and shared challenges?

- How can we help students become engaged citizens who also sustain civil disagreement, civic friendship, and thus American constitutional democracy?

- How can we help students pursue civic action that is authentic, responsible, and informed?

America’s Plural Yet Shared Story

- How can we integrate the perspectives of Americans from all different backgrounds when narrating a history of the U.S. and explicating the content of the philosophical foundations of American constitutional democracy?

- How can we do so consistently across all historical periods and conceptual content?

- How can this more plural and more complete story of our history and foundations also be a common story, the shared inheritance of all Americans?

Simultaneously Celebrating & Critiquing Compromise

- How do we simultaneously teach the value and the danger of compromise for a free, diverse, and self-governing people?

- How do we help students make sense of the paradox that Americans continuously disagree about the ideal shape of self-government but also agree to preserve shared institutions?

Civic Honesty, Reflective Patriotism

- How can we offer an account of U.S. constitutional democracy that is simultaneously honest about the wrongs of the past without falling into cynicism, and appreciative of the founding of the United States without tipping into adulation?

Balancing the Concrete & the Abstract

- How can we support instructors in helping students move between concrete, narrative, and chronological learning and thematic and abstract or conceptual learning?

Each theme is supported by key concepts that map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. They are vertically spiraled and developed to apply to K—5 and 6—12. Importantly, they are not standards, but rather offer a vision for the integration of history and civics throughout grades K—12.

Helping Students Participate

- How can I learn to understand my role as a citizen even if I’m not old enough to take part in government? How can I get excited to solve challenges that seem too big to fix?

- How can I learn how to work together with people whose opinions are different from my own?

- How can I be inspired to want to take civic actions on my own?

America’s Shared Story

- How can I learn about the role of my culture and other cultures in American history?

- How can I see that America’s story is shared by all?

Thinking About Compromise

- How can teachers teach the good and bad sides of compromise?

- How can I make sense of Americans who believe in one government but disagree about what it should do?

Honest Patriotism

- How can I learn an honest story about America that admits failure and celebrates praise?

Balancing Time & Theme

- How can teachers help me connect historical events over time and themes?

The Six Pedagogical Principles

EAD teacher draws on six pedagogical principles that are connected sequentially.

Six Core Pedagogical Principles are part of our Pedagogy Companion. The Pedagogical Principles are designed to focus educators’ effort on techniques that best support the learning and development of student agency required of history and civic education.

EAD teachers commit to learn about and teach full and multifaceted historical and civic narratives. They appreciate student diversity and assume all students’ capacity for learning complex and rigorous content. EAD teachers focus on inclusion and equity in both content and approach as they spiral instruction across grade bands, increasing complexity and depth about relevant history and contemporary issues.

Growth Mindset and Capacity Building

EAD teachers have a growth mindset for themselves and their students, meaning that they engage in continuous self-reflection and cultivate self-knowledge. They learn and adopt content as well as practices that help all learners of diverse backgrounds reach excellence. EAD teachers need continuous and rigorous professional development (PD) and access to professional learning communities (PLCs) that offer peer support and mentoring opportunities, especially about content, pedagogical approaches, and instruction-embedded assessments.

Building an EAD-Ready Classroom and School

EAD teachers cultivate and sustain a learning environment by partnering with administrators, students, and families to conduct deep inquiry about the multifaceted stories of American constitutional democracy. They set expectations that all students know they belong and contribute to the classroom community. Students establish ownership and responsibility for their learning through mutual respect and an inclusive culture that enables students to engage courageously in rigorous discussion.

Inquiry as the Primary Mode for Learning

EAD teachers not only use the EAD Roadmap inquiry prompts as entry points to teaching full and complex content, but also cultivate students’ capacity to develop their own deep and critical inquiries about American history, civic life, and their identities and communities. They embrace these rigorous inquiries as a way to advance students’ historical and civic knowledge, and to connect that knowledge to themselves and their communities. They also help students cultivate empathy across differences and inquisitiveness to ask difficult questions, which are core to historical understanding and constructive civic participation.

Practice of Constitutional Democracy and Student Agency

EAD teachers use their content knowledge and classroom leadership to model our constitutional principle of “We the People” through democratic practices and promoting civic responsibilities, civil rights, and civic friendship in their classrooms. EAD teachers deepen students’ grasp of content and concepts by creating student opportunities to engage with real-world events and problem-solving about issues in their communities by taking informed action to create a more perfect union.

Assess, Reflect, and Improve

EAD teachers use assessments as a tool to ensure all students understand civics content and concepts and apply civics skills and agency. Students have the opportunity to reflect on their learning and give feedback to their teachers in higher-order thinking exercises that enhance as well as measure learning. EAD teachers analyze and utilize feedback and assessment for self-reflection and improving instruction.

EAD teachers commit to learn about and teach full and multifaceted historical and civic narratives. They appreciate student diversity and assume all students’ capacity for learning complex and rigorous content. EAD teachers focus on inclusion and equity in both content and approach as they spiral instruction across grade bands, increasing complexity and depth about relevant history and contemporary issues.

Growth Mindset and Capacity Building

EAD teachers have a growth mindset for themselves and their students, meaning that they engage in continuous self-reflection and cultivate self-knowledge. They learn and adopt content as well as practices that help all learners of diverse backgrounds reach excellence. EAD teachers need continuous and rigorous professional development (PD) and access to professional learning communities (PLCs) that offer peer support and mentoring opportunities, especially about content, pedagogical approaches, and instruction-embedded assessments.

Building an EAD-Ready Classroom and School

EAD teachers cultivate and sustain a learning environment by partnering with administrators, students, and families to conduct deep inquiry about the multifaceted stories of American constitutional democracy. They set expectations that all students know they belong and contribute to the classroom community. Students establish ownership and responsibility for their learning through mutual respect and an inclusive culture that enables students to engage courageously in rigorous discussion.

Inquiry as the Primary Mode for Learning

EAD teachers not only use the EAD Roadmap inquiry prompts as entry points to teaching full and complex content, but also cultivate students’ capacity to develop their own deep and critical inquiries about American history, civic life, and their identities and communities. They embrace these rigorous inquiries as a way to advance students’ historical and civic knowledge, and to connect that knowledge to themselves and their communities. They also help students cultivate empathy across differences and inquisitiveness to ask difficult questions, which are core to historical understanding and constructive civic participation.

Practice of Constitutional Democracy and Student Agency

EAD teachers use their content knowledge and classroom leadership to model our constitutional principle of “We the People” through democratic practices and promoting civic responsibilities, civil rights, and civic friendship in their classrooms. EAD teachers deepen students’ grasp of content and concepts by creating student opportunities to engage with real-world events and problem-solving about issues in their communities by taking informed action to create a more perfect union.

Assess, Reflect, and Improve

EAD teachers use assessments as a tool to ensure all students understand civics content and concepts and apply civics skills and agency. Students have the opportunity to reflect on their learning and give feedback to their teachers in higher-order thinking exercises that enhance as well as measure learning. EAD teachers analyze and utilize feedback and assessment for self-reflection and improving instruction.