The curated resources linked below are an initial sample of the resources coming from a collaborative and rigorous review process with the EAD Content Curation Task Force.

Reset All

Reset All

Argue real Supreme Court cases, and put your lawyering skills to the test.

The Roadmap

iCivics, Inc.

Do you like running things? Branches of Power lets you do something that no one else can: control all three branches of the U.S. government.

The Roadmap

iCivics, Inc.

This collection of historical biographies tells the story of civic leaders through the lens of the DKP's 10 Questions for Changemakers.

The Roadmap

The Democratic Knowledge Project - Harvard University

On the occasion of the launch of the Mandela Children’s Fund, Nelson Mandela said, “There can be no keener revelation of a society's soul than the way in which it treats its children.” Children have often been caught up and played a role in the ideological and political movements that have taken place throughout U.S. History. What can we learn about these political and ideological movements through the lens of children and their experiences? When we frame our study of the past through the experiences of children and adolescents, we create pathways for connection and curiosity for our students. There are many ways you might use these sources in your curriculum. Use these sources individually, as you cover a particular era, or collectively, as students examine change and continuity in the experiences of children and teens over time. Sources are indexed below by theme and era and each source includes a brief description as well as guiding questions for use in the classroom.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by SubthemeEducation and its Impact on Children and Teens (12)Children and Public Activism (7)

- Primary Resources by Era/DateColonial Era (3)Nineteenth Century (3)1930s - 1940s (3)1940s, 50s, and 60s (9)Early Twentieth Century and WWI (6)

- All 24 Primary ResourcesContract for the Indenture of Elizabeth Fortune, Aged 9, 1723Contract for the Indenture of Elizabeth Fortune, Aged 9, 1723Transcript

John Fortune and Maria his wife have by these presents put, placed, and bound their daughter Elizabeth Fortune aged nine years the first day of March last past as an apprentice with the Said Elizabeth Sharpas

as an apprentice with her, the said Elizabeth Sharpas, to dwell from the day of the date of these presents for and during the term of Nine Years…The Said Elizabeth Fortune unto according to her power, wit, and ability and honestly and obediently in all things shall behave herself towards her said Mistress and all hers and shall not contract matrimony during the said Term.

Elizabeth Sharpas for her part promises, Covenants, agrees that she the said Elizabeth Sharpas apprenticed Elizabeth Fortune in the art and skill of housewifery.

This document provides a glimpse into the experiences of colonial children who spent much of their childhood working for families that were not their own. This indenture arraignment also highlights the kinds of skills and education that were valued for girls. Namely, Elizabeth Fortune is said to receive training in the “art of housewifery” in exchange for her service.

CitePrintShare“Indenture of Elizabeth Fortune, September 10, 1723,” Women & the American Story, https://wams.nyhistory.org/settler-colonialism-and-revolution/settler-colonialism/children-at-work/#. Accessed 1 April 2022.

Needlework by Sarah Anne Janeway, 1783 - Training for domestic workSewn Sampler made by 11-year-old Sarah Anne Janeway, 1783Young colonial girls raised in wealthy households were trained in the skills of a housewife early on. Samplers like this one displayed a girl's aptitude for needlework and could be hung as a piece of art in a family household.

CitePrintShare“Symbols of Accomplishment - Women & the American Story.” Women & the American Story, https://wams.nyhistory.org/settler-colonialism-and-revolution/settler-colonialism/symbols-of-accomplishment/#. Accessed 1 April 2022.

A New England Primer, 1803 - The role of religion in educationIn colonial New England, a primer like this one may have been in use as early as 1690. Children first learned their ABCs and basic literacy through primers. Since the Bible was seen as the primary means through which a child would attain literacy, these primers would often incorporate religious themes and morals.

CitePrintShareWestminster Assembly. “The New-England primer,” Boston: Printed for and sold by A. Ellison, in Seven-Star Lane, 1773. Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/22023945/>. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Perry Lewis (b. 1850), formerly enslaved, recounts his childhood in Baltimore, M.D. - Enslaved children and lack of access to educationPerry Lewis (b. 1850), formerly enslaved, recounts his childhood in Baltimore, M.D.TranscriptAs you know the mother was the owner of the children that she brought into the world Mother being a slave made me a slave. She cooked and worked on the farm, ate whatever was in the farmhouse and did her share of work to keep and maintain the Tolsons.

They being poor, not having a large place or a number of slaves to increase their wealth, made them little above the free colored people and with no knowledge, they could not teach me or anyone else to read…

In my childhood days, I played marbles, this was the only game I remember playing. As I was on a small farm, we did not come in contact much with other children and heard no childrens’ songs. I therefore do not recall the songs we sang.

Records from the Federal Writers Project are of immense importance in documenting and preserving the experiences of those who survived enslavement. ; Lewis’ account includes reference to the concept of hypodescent, which allowed intergenerational, chattel slavery to persist in the U.S. Lewis also makes note of his lack of access to education and some memories of his childhood.

1- Miletich, Patricia. “Religion and Literacy in Colonial New England | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History |, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/lesson-plan/religion-and-literacy-colonial-new-england. Accessed 2 April 2022.

- For more on the Federal Writer’s Project see Smith, Clint. “The Value of the Federal Writers' Project Slave Narratives.” The Atlantic, 9 February 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/03/federal-writers-project/617790/. Accessed 19 April 2022.

CitePrintShareFederal Writers' Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 8, Maryland, Brooks-Williams. 1936. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/mesn080/>. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Before and After Photos of Children enrolled in Carlilse Residential Indian School, 1890s - Residential School SystemOne of the “before-and-after-education” photographs of Sioux boys taken before arriving at boarding school in the 1890s.At Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, and other residential schools like it, Native American children and teens were required to give up their tribal traditions and culture. Carlisle opened in 1879 as the first government-run residential school, aimed at forcing Indigenous youth to assimilate to White culture. These before and after photos were taken as a way to demonstrate the efforts at assimilation.

1- “Richard Henry Pratt Carlisle Indian School.” Carlisle Indian School Project, https://carlisleindianschoolproject.com/past/. Accessed 2 April 2022.

CitePrintShareImage 1: "Sioux boys as they arrived at Carlisle," Digital Public Library of America, http://dp.la/item/d7ca78d98ae563bfefd20c2620613c8b. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Image 2: "Sioux boys 3 years after arriving at Carlisle," Digital Public Library of America, http://dp.la/item/f7b6ae7adfd4a9c9ecbceaf3af5fa8b5. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Sample Program For One Week - Residential School SystemSample daily program for one week at an Indian school, 1914Life for a student at the Carlisle Indian School was highly regimented and militaristic, signaling the government’s influence on the school’s mission and identity. This source, paired with the images above, offers a glimpse into the daily experience of those enrolled in this program as well as information about the aims of the federal government in establishing institutions such as Carlisle.

CitePrintShare“Cover letter, January 23, 1914, with attached sample daily program for one week at an Indian school”; 1/1914; Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group 75. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/cover-letter-january-23-1914-with-attached-sample-daily-program-for-one-week-at-an-indian-school. Accessed March 24, 2022.

Mary Ann Yahiro recites the Pledge of Allegiance at Raphael Weill School in San Francisco before being sent to Topaz internment camp in Utah, April 1942 - Japanese IntenmentMary Ann Yahiro, center, recites the Pledge of Allegiance at Raphael Weill School in San Francisco in April 1942 before being sent to Topaz internment camp in Utah.This photograph shows a group of children in the Weil Public School reciting the pledge of allegiance to the U.S. flag. The young girl in the front row center is Helen Mihara. A few months before this image was taken, Helen’s father, a San Francisco businessman, was arrested and detained in a Department of Justice camp for “enemy aliens.” Soon after this image was taken, Helen and her mother were placed in Tule Lake Relocation Center. Her mother later died in detention.

1- “San Francisco, Calif., April 1942 - Children of the Weill public school, from the so-called international settlement, shown in a flag pledge ceremony. Some of them are evacuees of Japanese ancestry who will be housed in War relocation authority centers for.” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2001705926/. Accessed 5 April 2022.

CitePrintShareLange, Dorothea, photographer. San Francisco, Calif., April- Children of the Weill public school, from the so-called international settlement, shown in a flag pledge ceremony. Some of them are evacuees of Japanese ancestry who will be housed in War relocation authority centers for the duration. [April] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2001705926/>. Accessed April 10, 2022.

TIME Magazine Feature on the American “teen-ager," 1944 - American Teenage Girls“The Invention of the American “teen-ager,” 1944Although it is not a certainty, some historians believe that the concept of the American “teenager” originated sometime in the 1940s. A liminal age, the teenager was neither child nor adult. This 1944 TIME Magazine article detailed the “life of the American Teenager” by photojournalist Nina Leen. The full article offers a glimpse into the perception of teens but also offers opportunities for students to consider the rise of the middle class, social status, and race in the middle of the twentieth century.

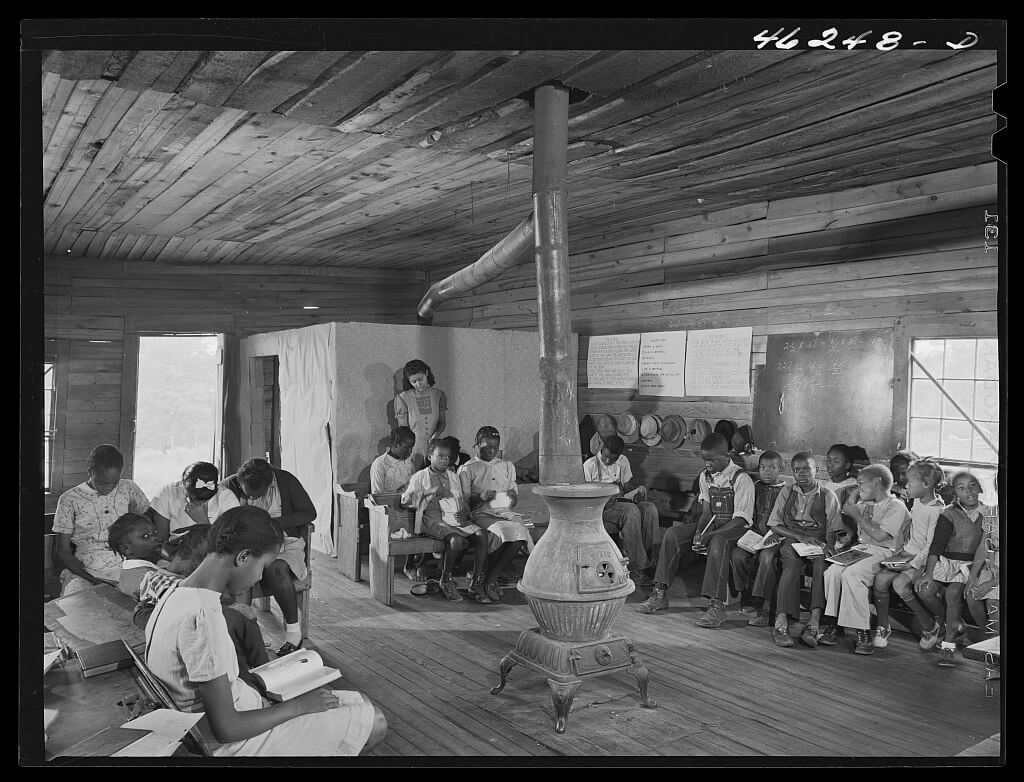

Separate but Unequal: Two classrooms before Brown v. Board of Education, Georgia, 1941 - School SegregationSchool segregation was among the most central concerns of the Civil Rights Movement since the 1930s. Activists for school integration argued that separate was not equal and every child, regardless of race, was entitled to education in a safe learning environment. These two images depict daily life in segregated classrooms in the same year, 1941. Brown v. Board of Education would not be passed for more than a decade.

1- “Recovery Programs.” Recovery Programs | DPLA, https://dp.la/exhibitions/new-deal/recovery-programs/farm-security-administration?item=409. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareImage 1: Delano, J., photographer. (1941) Veazy, Greene County, Georgia. The one-teacher Negro school in Veazy, south of Greensboro. United States Greene County Georgia Veazy, 1941. Oct. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017796657/. Accessed April 10, 2022.

Image 2: Delano, J., photographer. (1941) Siloam, Greene County, Georgia. Classroom in the school. United States Greene County Siloam Georgia, 1941. Oct. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017796554/. Accessed April 10, 2022.

Telegram from Parents of the Little Rock Nine to President Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1957-58 - School IntegrationTelegram from Parents of the Little Rock Nine to President Dwight D. EisenhowerWritten three years after the passage of Brown v. Board of Education, this telegram to President Eisenhower details the feelings of parents of the Little Rock Nine, who were a part of the busing program to integrate the Little Rock school system. The Little Rock Nine were the first African American students to enter Little Rock’s Central High School in Arkansas. The parents note that because of the supreme court ruling their “faith in democracy” had been renewed.

1- “The Little Rock Nine.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/little-rock-nine. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareTelegram from Parents of the Little Rock Nine to President Dwight D. Eisenhower; 10/1957; OF 142-A-5 Negro Matters - Colored Question (5), 1957 - 1958; Official Files, 1953 - 1961; Collection DDE-WHCF: White House Central Files (Eisenhower Administration), 1953 - 1961; Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Abilene, KS. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/telegram-parents-little-rock-nine-to-president-eisenhower. Accessed April 1, 2022.

African American children on their way to PS204, 82nd Street, and 15th Avenue, pass mothers protesting the busing of children to achieve integration, 1965 - School IntegrationAfrican American children on their way to PS204, 82nd Street, and 15th Avenue, pass mothers protesting the busing of children to achieve integrationEven after the passage of Brown v. Board of Education, school integration was protested. This image shows African American children entering their new school while white mothers protest school integration

CitePrintShareDemarsico, Dick, photographer. African American children on way to PS204, 82nd Street and 15th Avenue, pass mothers protesting the busing of children to achieve integration (1965). Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2004670162/>. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Audio Recording: Conversation with 11 and 12-year-old black females, Meadville, Mississippi, 1973 - Daily life for two pre-teens in DetriotThis conversation was originally recorded as part of an effort to archive regional dialects by the Library of Congress. It also provides a glimpse into the daily lives of pre-teen girls, including racial discrimination they faced in their school community.

Audio Recording: Conversation with 11 and 12-year-old black females, Meadville, Mississippi

CitePrintShareUnidentified, and Walt Wolfram. Conversation with 11 and 12-year-old black females, Meadville, Mississippi. to 1973, 1972. Audio. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/afccal000213/>. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Mother Jones and Children Laborers go on Strike, 1903Mother Jones and Children Laborers go on Strike, 1903In July of 1903, Mother Jones led a march from Philadelphia to the home of President Rosevelt to protest the unsafe labor conditions of children working in mills. The story of Mother Jones and the children who accompanied her on her march showcases not only youth activism but also women in the labor movement at the turn of the century.

1- Lauren Cooper. “July 7, 1903: March of the Mill Children.” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/mother-jones-march-mill-children/. Accessed 3 April 2022.

CitePrintShare"Mother" Jones and her army of striking textile workers starting out for their descent on New York The textile workers of Philadelphia say they intend to show the people of the country their condition by marching through all the important cities”; 1903; Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2015649893/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Child Labor Standards, 1916Child Labor StandardsThis ad was created after the passage of the Keating-Own Child Labor Act of 1916. This act limited the working hours of children and placed an age requirement of the age of 16 for any working child. It also forbade the interstate sale of goods produced in factories that employed child labor.

CitePrintShare"Child Labor Standards"; ca. 1941-1945; Records of the Office of War Information, Record Group 208. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/child-labor-standards. April 1, 2022.

Girl Scouts and the War EffortGirl Scout Troup Plants a Victory Garden, 1917Girl Scout Pledge Card to Save for a Soldier, 1914After the US declared war in 1917, children were encouraged to support the war efforts. The Girl Scouts of America provided an opportunity for girls to become involved in volunteer work for the war effort. Organizations like the Girls Scouts and 4H typically trained girls for domestic work. Skills like sewing and first-aid were put to use in new ways for members of the Girl Scouts and 4H during WWI. Here, scouts planted a Victory Garden. Victory gardens, or liberty gardens, first appeared during WWI. The federal government encouraged citizens to plant vegetable gardens to mitigate any food shortages that resulted from the war.

1- Lauren Cooper. “July 7, 1903: March of the Mill Children.” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/mother-jones-march-mill-children/. Accessed 3 April 2022.

- Spring, Kelly A. “Girls' Volunteer Groups during World War I.” National Women's History Museum, https://www.womenshistory.org/resources/general/girls-volunteer-groups-during-world-war-i. Accessed 3 April 2022.

CitePrintShareImage 1: Harris & Ewing, photographer. NATIONAL EMERGENCY WAR GARDENS COM. GIRL SCOUTS GARDENING AT D.A.R. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2016867777/>. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Image 2: “Girl Scout Pledge Card "To Save for a Solder”. 1914. Girl Scout Archive Management Center. https://archives.girlscouts.org/Detail/objects/64958. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Boy Scouts as Bond Workers, 1917Boy Scouts as Bond Workers, 1917Boyscouts, like Girl Scouts, volunteered in the war effort during both WWI and II. Here, scouts who were too young to go to combat sell war bonds.

CitePrintShareBain News Service, Publisher. Boy Scouts as bond workers. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2014704734/>. Accessed April 10, 2022.

12-Year-Old Girl at the March on Washington, 196312-Year-Old Girl at the March on WashingtonOn August 28, 1963, thousands took part in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The March was instigated by a continuing lack of jobs for African Americans and the persistence of segregation. The march was influential in pressuring President John F. Kennedy to draft a strong civil rights bill. This photo depicts Edith Lee-Payne on her twelfth birthday. Edith attended the March with her mother.

1- “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom | The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute.” The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute |, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/march-washington-jobs-and-freedom. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintSharePhotograph 306-SSM-4C-61-32; Young Woman at the Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. with a Banner; 8/28/1963; Miscellaneous Subjects, Staff and Stringer Photographs, 1961 - 1974; Records of the U.S. Information Agency, Record Group 306; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/girl-march-on-washington-banner. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Protests in support of the 26th Amendment, 1969Protests in support of the 26th AmendmentThe 26th Amendment to the Constitution allowed for those 18 years old or older to vote in elections. Support for decreasing the voting age from 21 to 18 increased during World War II, as young men were conscripted to fight in the war as young as 18 but could not yet vote. This image depicts youth protestors in support of the 26th amendment.

1- “The 26th Amendment | Richard Nixon Museum and Library.” Nixon Presidential Library, 17 June 2021, https://www.nixonlibrary.gov/news/26th-amendment. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShare“Demonstration for reduction in voting age, Seattle, 1969”; Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, Museum of History & Industry, Seattle; https://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/digital/collection/imlsmohai/id/1715/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Little Spinner in Globe Cotton Mill, Augusta, Ga., 1909Little Spinner in Globe Cotton Mill, Augusta, Ga., 1909Images of children laborers at the turn of the century reveal the experiences of children who spent most of their days working in the oftentimes harsh and unsafe conditions of urban factories. After the Civil War, as industry grew in urban areas, children often worked in factories, in markets, and on the streets as vendors.

Children Working in a Textile Mill in Georgia, 1909Children Working in a Textile Mill in GeorgiaLike the image above, this source shows a young child operating machinery that he is not even tall enough to reach. Images like these and the one above were captured by activists for child labor laws. The Child labor standards act would be passed in 1916

1- Schuman, Michael. “History of child labor in the United States—part 1: little children working: Monthly Labor Review: US Bureau of Labor Statistics.” Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2017/article/history-of-child-labor-in-the-united-states-part-1.htm. Accessed 19 April 2022.

CitePrintSharePhotograph 102-LH-488; Bibb Mill No. 1, Macon, Ga.; 1/19/1909; Bibb Mill No. 1, Macon, Ga. Many youngsters here. Some boys and girls were so small they had to climb up onto the spinning frame to mend broken threads and to put back the empty bobbins.,; Records of the Children's Bureau, Record Group 102; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/bibb-mill. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Spread from Look magazine on sharecropping children, 1937Page from Look magazine, 1937 on sharecropping childrenThis magazine spread on sharecropping children was published the same year that President Rosevelt established the Farm Security Administration. The FSA was a New Deal agency that provided assistance and relief to agricultural workers impacted by drought and the Great Depression.

1- “Gardening for the Common Good.” Smithsonian Libraries, https://library.si.edu/exhibition/cultivating-americas-gardens/gardening-for-the-common-good. Accessed 19 April 2022.

CitePrintSharePages 18 and 19 of March Look magazine. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2017760274/>. April Accessed April 10, 2022.

Boys playing marbles, Farm Security Administration labor camp, Robstown, Texas, 1944Boys playing marbles, Farm Security Administration labor camp, Robstown, Texas, 1944During the Great Depression, The Farm Security Administration attempted to aid workers and farmers by setting up housing camps, providing loans and training to workers, among other forms of assistance. This source shows a group of children playing marbles in one of the FSA labor camps in Texas, offering a glimpse into daily life and play for children living through the Great Depression.

CitePrintShareRothstein, A., photographer. (1942) Boys playing marbles, FSA ... labor camp, Robstown, Texas. United States Robstown Texas, 1942. Jan. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017877649/. Accessed April 10, 2022.

School Closures during Little Rock Nine: Girls learn from Home, 1958 - School IntegrationSchool Closures during Little Rock 9: three pajama-clad white girls being educated via television during the period that the Little Rock schools were closed to avoid integration.In September 1958, Governor Faubus of Arkansas closed all Little Rock public high schools as a result of unrest due to integration. Known as the “Lost Year,” both teachers and students were blocked from their school buildings. This image shows three girls learning “remotely” during that time and offers a glimpse of the efforts to maintain continuity of education in the midst of upheaval.

1- “The Little Rock Nine.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/little-rock-nine. Accessed 4 April 2022.

- “Sept. 12, 1958: Little Rock Public Schools Closed.” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/little-rock-schools-closed/. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareO'Halloran, T. J., photographer. (1958) Little Rock, Ark. Attempts to reopen schools / TOH. Arkansas Little Rock, 1958. Sept. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003654390/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Letter from Linda Kelly, Sherry Bane, and Mickie Mattson to President Dwight D. Eisenhower Regarding Elvis Presley, 1953-1961Letter from Linda Kelly, Sherry Bane, and Mickie Mattson to President Dwight D. Eisenhower Regarding Elvis Presley, 1953-1961Celebrities were no exception to the draft during the Vietnam War. Elvis Presley joined the army in 1958 and, in this letter, three girls from Nevada ask President Eisenhower not to shave off his sideburns. This source offers a window into the lives of American teens as well as an example of the role teens played in the evolution and development of American pop culture.

1- Cosgrove, Ben. “The Invention of Teenagers: LIFE and the Triumph of Youth Culture.” Time.com, TIME, 28 September 2013, https://time.com/3639041/the-invention-of-teenagers-life-and-the-triumph-of-youth-culture/. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareBane, Sherry Author, Linda Author Kelly, and Mickie Author Mattson. Letter from Linda Kelly, Sherry Bane, and Mickie Mattson to President Dwight D. Eisenhower Regarding Elvis Presley. [Place of Publication Not Identified: Publisher Not Identified, 1958] Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2021667581/> Accessed April 4, 2022.

- Additional Resources

- Teacher's Guides and Analysis Tool | Getting Started with Primary Sources | Teachers | Programs | Library of Congress

- Document Analysis Overview | National Archives

- Activity Tools | DocsTeach

- Primary Source Activity Guide | EAD Team

Education for American Democracy

This lesson helps students explore the question, "What does it mean to be a good citizen, and how do citizens learn to use their power to make change?" using the work of civic entrepreneur Eric Liu.

The Roadmap

Facing History and Ourselves

Students explore how to evaluate the trustworthiness of an expert's claims, using a case study on Dr. Oz and his promotion of green coffee bean extract. Students discover that through the application of five key questions, they can be more confident that a specific claim made by an expert is trustworthy.

The Roadmap

High Resolves

Freedom of speech is so fundamental to the nation’s guiding principles that it is protected in the First Amendment to the Constitution. At the same time, the U.S. Government has imposed limits on that freedom throughout the nation’s history, and not all Americans have enjoyed equal freedom of speech under the law. This set of sources explores freedom of speech through the nation’s laws, courts, protests and controversies. Sources include historical examinations of free speech before the Civil War, during the early 20th century, and during the Civil Rights Era; the Spotlight Kit also explores contemporary issues, including recent controversies that remain unresolved. Sources are indexed below by type and by era, and each source includes a brief description as well as guiding questions for use in the classroom. While longer texts include a link to the full original text, the excerpt provided here is intentionally chosen and edited for classroom use.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by Era/Date1776 - 1865 (3)1900 - 1957 (4)1960s (4)1970s-80s (3)2000 - present (4)

- All 18 Primary ResourcesThe U.S. Bill of Rights (ratified December 15, 1791)

It’s important for students to see the original text of the amendment.

Amendment ICongress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

The Sedition Act, U.S. Congress, 1798Shortly after the ratification of the Bill of Rights, Congress passed the Alien and Sedition Acts. The Sedition Act, part of which is cited here, limits freedom of speech that is critical of the government, particularly during times of war. Enforcement of the act was controversial, suspected of targeting only political opponents.

“SEC. 2. And be it farther enacted, That if any person shall write, print, utter or publish, or shall cause or procure to be written, printed, uttered or published, or shall knowingly and willingly assist or aid in writing, printing, uttering or publishing any false, scandalous and malicious writing or writings against the government of the United States, or either house of the Congress of the United States, or the President of the United States, with intent to defame the said government, or either house of the said Congress, or the said President, or to bring them, or either of them, into contempt or disrepute; or to excite against them, or either or any of them, the hatred of the good people of the United States, or to stir up sedition within the United States, or to excite any unlawful combinations therein, for opposing or resisting any law of the United States, or any act of the President of the United States, done in pursuance of any such law, or of the powers in him vested by the constitution of the United States, or to resist, oppose, or defeat any such law or act, or to aid, encourage or abet any hostile designs of any foreign nation against United States, their people or government, then such person, being thereof convicted before any court of the United States having jurisdiction thereof, shall be punished by a fine not exceeding two thousand dollars, and by imprisonment not exceeding two years.”CitePrintShareAlien and Sedition Acts (1798) | National Archives. (2022, February 8). National Archives |. Retrieved from https://www.archives.gov/milestone-documents/alien-and-sedition-acts#sedition

Anti-slavery petition despite “The Gag Rule,” (1830s)Anti-slavery petition despite “The Gag Rule” 1830s“On May 26, 1836, the House of Representatives adopted a ‘Gag Rule’ stating that all petitions regarding slavery would be tabled without being read, referred, or printed….The enactment of the Gag Rule, rather than discouraging petitioners, energized the anti-slavery movement to flood the Capitol with written demands. Activists held up the suppression of debate as an example of the slaveholding South’s infringement of the rights of all Americans.”

CitePrintShareAdams, J. Q. (n.d.). The Gag Rule | National Museum of American History. National Museum of American History. Retrieved from https://americanhistory.si.edu/democracy-exhibition/beyond-ballot/petitioning/gag-rule

The National Women’s Party protests for suffrage (photograph, 1917)[Policewoman arrests Florence Youmans of Minnesota and Annie Arniel (center) of Delaware for refusing to give up their banners. 1917]The National Woman’s Party protested for suffrage.

“Mrs. Annie Arniel, Wilmington, Delaware, did picket duty at the White House beginning in 1917. She was one of the first six suffrage prisoners and served eight jail sentences: three days in June 1917 and sixty days in Occoquan Workhouse in August-September 1917 for picketing; fifteen days in August 1918 for the Lafayette Square meeting; and five sentences of five days each in January and February 1919, for watchfire demonstrations. Source: Doris Stevens, Jailed for Freedom (New York: Boni and Liveright, 1920), 355.”

CitePrintSharePolicewoman arrests Florence Youmans of Minnesota and Annie Arniel (center) of Delaware for refusing to give up their banners. (n.d.). Library of Congress. Retrieved from https://www.loc.gov/item/mnwp000073

“Freedom of Speech” (painting, Norman Rockwell, 1943)Freedom of Speech, Norman Rockwell. 1943. ©SEPS: Curtis Publishing, Indianapolis, IN.This iconic image from Norman Rockwell’s “Four Freedoms” paintings depicts a particular image of free speech; students can make a wide range of observations about the image.

CitePrintShareNorman Rockwell Four Freedoms paintings inspired by Franklin Roosevelt. (n.d.). Enduring Ideals: Rockwell, Roosevelt & the Four Freedoms. Retrieved from https://rockwellfourfreedoms.org/about-the-exhibit/rockwells-four-freedoms/

The March on Washington (photograph, 1963)Demonstrators at the civil rights march on Washington, D.C. demand an end to police violence, August 28, 1963While the Martin Luther King, Jr. “I Have a Dream” speech is used frequently in schools, students do not as often have the opportunity to explore the full set of demands for the march, the “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom” which had first been proposed in 1941. The protest signs in this image are echoed in contemporary protests now.

CitePrintShareBrady, S. (n.d.). Policing the Police: A Civil Rights Story | Origins. Origins: Current Events in Historical Perspective. Retrieved from https://origins.osu.edu/article/policing-police-civil-rights-story?language_content_entity=en

The Memphis sanitation workers’ strike (photograph, 1968)1968, Memphis, Tennessee, USA — Civil Rights Marchers with “I Am A Man” Signs — Image by © Bettmann/CORBISAny number of images from the Civil Rights era would benefit a unit on freedom of speech, but this particular image does a few things: (1) marks the occasion immediately before Martin Luther King’s assassination; (2) provides an image of a single text used over and over, in contrast to the image above with multiple demands; and (3) juxtaposes protesters exercising their first amendment rights with a police force wielding weapons.

CitePrintShareCooper, L. (n.d.). Sanitation workers' strike in Memphis, Tenn. in 1968. Zinn Education Project. Retrieved from https://www.zinnedproject.org/slide/slide_memphis_strike/civil-rights-marchers-with-i-am-a-man-signs/

Chicano Student Movement newspaper (image and newspaper text, 1968)Chicano Student Movement Newspaper (1968)Chicano Student Movement Newspaper (1968)The East L.A. Walkouts, involving thousands of students from L.A. public schools, included numerous demands for school reform. Students protested the lack of inclusion of their history in the curriculum, widespread prohibitions against speaking Spanish in schools, and inequity of both opportunity and instruction. Police responded to student protesters with violence.

Tinker v. Des Moines (1969)In this case, John Tinker (15), Christopher Eckhardt (16), and Mary Beth Tinker (13) chose to wear black armbands to their schools as a silent protest against the War in Vietnam. School authorities sent them home until they would agree not to wear the armbands. The case, which made its way to the Supreme Court, became a landmark decision that laid the groundwork not only for students to exercise freedom of speech in school (with some limits imposed by this case and others), but also to exercise other Constitutional rights.

Mr. Justice FORTAS delivered the opinion of the Court.“First Amendment rights, applied in light of the special characteristics of the school environment, are available to teachers and students. It can hardly be argued that either students or teachers shed their constitutional rights to freedom of speech or expression at the schoolhouse gate….

…In our system, state-operated schools may not be enclaves of totalitarianism. School officials do not possess absolute authority over their students. Students in school as well as out of school are 'persons' under our Constitution. They are possessed of fundamental rights which the State must respect, just as they themselves must respect their obligations to the State. In our system, students may not be regarded as closed-circuit recipients of only that which the State chooses to communicate. They may not be confined to the expression of those sentiments that are officially approved. In the absence of a specific showing of constitutionally valid reasons to regulate their speech, students are entitled to freedom of expression of their views…

…A student's rights, therefore, do not embrace merely the classroom hours. When he is in the cafeteria, or on the playing field, or on the campus during the authorized hours, he may express his opinions, even on controversial subjects like the conflict in Vietnam, if he does so without 'materially and substantially interfer(ing) with the requirements of appropriate discipline in the operation of the school' and without colliding with the rights of others.”

CitePrintShareJohn F. TINKER and Mary Beth Tinker, Minors, etc., et al., Petitioners, v. DES MOINES INDEPENDENT COMMUNITY SCHOOL DISTRICT et al. (n.d.). Legal Information Institute. Retrieved from https://www.law.cornell.edu/supremecourt/text/393/503

Demaske, Chris. “Village of Skokie v. National Socialist Party of America (Ill).” Middle Tennessee State University, https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/728/village-of-skokie-v-national-socialist-party-of-america-ill. Accessed 20 November 2022.

Goldberger, David. “The Skokie Case: How I Came to Represent the Free Speech Rights of Nazis.” American Civil Liberties Union, 2 March 2020, https://www.aclu.org/issues/free-speech/rights-protesters/skokie-case-how-i-came-represent-free-speech-rights-nazis. Accessed 20 November 2022.

Village of Skokie v. National Socialist Party of America [photographs,1978]“In Village of Skokie v. National Socialist Party of America, 373 N. E. 2d 21 (Ill. 1978), the Illinois Supreme Court held that the display of swastikas did not constitute fighting words,” setting legal precedent for other freedom of speech and hate speech cases that followed. The neo-Nazi group pictured in these photographs fought for the right to march in Chicago and Skokie Illinois, the latter a predominantly Jewish town with a significant number of Holocaust survivors. The bottom photograph shows counter-demonstrators.

CitePrintShareDemaske, Chris. “Village of Skokie v. National Socialist Party of America (Ill).” Middle Tennessee State University, https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/728/village-of-skokie-v-national-socialist-party-of-america-ill. Accessed 20 November 2022.

Goldberger, David. “The Skokie Case: How I Came to Represent the Free Speech Rights of Nazis.” American Civil Liberties Union, 2 March 2020, https://www.aclu.org/issues/free-speech/rights-protesters/skokie-case-how-i-came-represent-free-speech-rights-nazis. Accessed 20 November 2022.

Book banning (Photograph, 1980)Photo, Kurt VonnegutTranscriptIn this photo, author Kurt Vonnegut Jr., speaks to reporters on a federal court ruling calling for a trial to determine if a Long Island school board can ban a number of books, including his "Slaughterhouse Five," at New York Civil Liberty offices in 1980. (AP Photo-File, used with permission from the Associated Press)

The issue of school boards banning controversial texts from classrooms and school libraries has resurfaced in a significant number of places in 2021-22; this photograph, with visible titles to investigate, adds a historical context to the perennial issue.

CitePrintShareWebb, S. L. (n.d.). Book Banning | The First Amendment Encyclopedia. Middle Tennessee State University. Retrieved from https://www.mtsu.edu/first-amendment/article/986/book-banning

Ronald Reagan, Speech at Moscow State University (1988)This speech, delivered before the fall of the Soviet Union, provides another definition of freedom and its centrality to American democracy and to democracy writ large.

“...Go to any university campus, and there you'll find an open, sometimes heated discussion of the problems in American society and what can be done to correct them. Turn on the television, and you'll see the legislature conducting the business of government right there before the camera, debating and voting on the legislation that will become the law of the land. March in any demonstrations, and there are many of them - the people's right of assembly is guaranteed in the Constitution and protected by the police.But freedom is more even than this: Freedom is the right to question, and change the established way of doing things. It is the continuing revolution of the marketplace. It is the understanding that allows us to recognize shortcomings and seek solutions. It is the right to put forth an idea, scoffed at by the experts, and watch it catch fire among the people. It is the right to stick - to dream - to follow your dream, or stick to your conscience, even if you're the only one in a sea of doubters.

Freedom is the recognition that no single person, no single authority of government has a monopoly on the truth, but that every individual life is infinitely precious, that every one of us put on this world has been put there for a reason and has something to offer.”

CitePrintShareReagan, R. W. (n.d.). Digital History. Digital History. Retrieved from http://www.digitalhistory.uh.edu/disp_textbook.cfm?smtid=3&psid=1234

Snyder v. Phelps (2011)In this case, the Westboro Baptist Church staged a public protest on public grounds near the funeral of a soldier who was killed in active duty in Iraq. They staged similar protests at military funerals around the country; these protests were notable for the incendiary nature of the content of their picket signs, which expressed anti-LGBTQ sentiments and blamed the US Government and US military for its tolerance of LGBTQ soldiers and issues. The Court’s opinion, referencing other cases as precedents, held that freedom of speech cannot hinge on the “offensive or disagreeable” nature of the speech.

SNYDER v. PHELPSChief Justice Roberts , Opinion of the Court (March 2, 2011)

“Simply put, the church members had the right to be where they were. Westboro alerted local authorities to its funeral protest and fully complied with police guidance on where the picketing could be staged. The picketing was conducted under police supervision some 1,000 feet from the church, out of the sight of those at the church. The protest was not unruly; there was no shouting, profanity, or violence.

…Given that Westboro’s speech was at a public place on a matter of public concern, that speech is entitled to ‘special protection’ under the First Amendment . Such speech cannot be restricted simply because it is upsetting or arouses contempt. ‘If there is a bedrock principle underlying the First Amendment , it is that the government may not prohibit the expression of an idea simply because society finds the idea itself offensive or disagreeable.’ Texas v. Johnson, 491 U. S. 397, 414 (1989) . Indeed, ‘the point of all speech protection … is to shield just those choices of content that in someone’s eyes are misguided, or even hurtful.’ Hurley v. Irish-American Gay, Lesbian and Bisexual Group of Boston, Inc., 515 U. S. 557, 574 (1995).”

CitePrintShareSNYDER v. PHELPS. (n.d.). Legal Information Institute. Retrieved from https://www.law.cornell.edu/supct/html/09-751.ZO.html

Schenck v. United States (1919)In this landmark case, the Supreme Court established limitations to freedom of speech – the notions of “clear and present danger” and restrictions during time of war. The case continues to reverberate throughout American History as a point of reference and as formal legal precedence for other cases.

- JUSTICE HOLMES delivered the opinion of the court.

“We admit that, in many places and in ordinary times, the defendants, in saying all that was said in the circular, would have been within their constitutional rights. But the character of every act depends upon the circumstances in which it is done. ..The most stringent protection of free speech would not protect a man in falsely shouting fire in a theatre and causing a panic. It does not even protect a man from an injunction against uttering words that may have all the effect of force. …The question in every case is whether the words used are used in such circumstances and are of such a nature as to create a clear and present danger that they will bring about the substantive evils that Congress has a right to prevent. It is a question of proximity and degree. When a nation is at war, many things that might be said in time of peace are such a hindrance to its effort that their utterance will not be endured so long as men fight, and that no Court could regard them as protected by any constitutional right.”

CitePrintShareWhite, E. D. (n.d.). Schenck v. United States :: 249 US 47 (1919). Justia US Supreme Court Center. Retrieved from https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/249/47/#tab-opinion-1928047

Mahanoy Area School Dist. v. B. L. (news clip, 2021)Mahanoy Area School District v. B.L.Transcript“June 23 (Reuters) - The U.S. Supreme Court on Wednesday ruled in favor of a Pennsylvania teenager who sued after a profanity-laced social media post got her banished from her high school's cheerleading squad in a closely watched free speech case, but it declined to outright bar public schools from regulating off-campus speech.

The justices ruled 8-1 that the punishment that Mahanoy Area School District officials gave the plaintiff, Brandi Levy, for her social media post - made on Snapchat at a local convenience store in Mahanoy City on a weekend - violated her free speech rights under the U.S. Constitution's First Amendment. The decision was authored by liberal Justice Stephen Breyer.”

The ubiquity of social media and cell phones have added complexity to the question of students’ freedom of speech (which had been otherwise “settled” in the Tinker v. Des Moines case); this recent case examined the question of how far schools’ regulation of, and consequences for, student speech can extend.

CitePrintShareImage: SHERMAN, M. (2021, April 28). US Supreme Court weighs Pa. student's Snapchat profanity case. WTAE. Retrieved from https://www.wtae.com/article/supreme-court-weighs-pennsylvania-student-snapchat-profanity-case/36279606#

Text: Chung, A. (2021, June 23). Cheerleader prevails at U.S. Supreme Court in free speech case. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/legal/litigation/us-supreme-court-hands-victory-cheerleader-free-speech-case-2021-06-23/

Roth v. United States (1957)In this case, the Supreme Court considered whether material deemed “obscene” should be protected by the First Amendment. The majority opinion declares that it is not protected speech; the opinion raises fundamental questions about how society determines what is and is not “obscene.” This question arises throughout U.S. history, in subsequent cases about public use of profanity, restrictions of speech in broadcast media, school book bans, and regulation of student behavior on social media, included in other sources in this collection.

Roth v. United States, 354 U.S. 476 (1957)- JUSTICE BRENNAN delivered the opinion of the Court.

“All ideas having even the slightest redeeming social importance -- unorthodox ideas, controversial ideas, even ideas hateful to the prevailing climate of opinion -- have the full protection of the guaranties, unless excludable because they encroach upon the limited area of more important interests. But implicit in the history of the First Amendment is the rejection of obscenity as utterly without redeeming social importance. …We hold that obscenity is not within the area of constitutionally protected speech or press. It is strenuously urged that these obscenity statutes offend the constitutional guaranties because they punish incitation to impure sexual thoughts, not shown to be related to any overt antisocial conduct which is or may be incited in the persons stimulated to such thoughts….

The fundamental freedoms of speech and press have contributed greatly to the development and wellbeing of our free society and are indispensable to its continued growth. Ceaseless vigilance is the watchword to prevent their erosion by Congress or by the States. The door barring federal and state intrusion into this area cannot be left ajar; it must be kept tightly closed, and opened only the slightest crack necessary to prevent encroachment upon more important interests. It is therefore vital that the standards for judging obscenity safeguard the protection of freedom of speech and press for material which does not treat sex in a manner appealing to prurient interest.

[The Court suggests] this test: whether, to the average person, applying contemporary community standards, the dominant theme of the material, taken as a whole, appeals to prurient interest.”

CitePrintShare“Roth v. United States :: 354 U.S. 476 (1957).” Justia US Supreme Court, https://supreme.justia.com/cases/federal/us/354/476/. Accessed 13 November 2022.

Parents at a school board meeting, Loudoun County VA (photograph, 2021)As stated above, the issue of school boards banning controversial texts from classrooms and school libraries has resurfaced in a significant number of places in 2021-22.

CitePrintShareOliphant, J., & Borter, G. (2021, June 23). Partisan war over teaching history and racism stokes tensions in U.S. schools. Reuters. Retrieved from https://www.reuters.com/world/us/partisan-war-over-teaching-history-racism-stokes-tensions-us-schools-2021-06-23/

House Bill 2670, State of Tennessee (2022) and House Bill 1557, State of Florida (2022)These recent bills, and others like them in other states, raise questions about the power of legislatures, school systems and departments of education to circumscribe what teachers are, or are not, allowed to teach about in schools, colleges and universities

HOUSE BILL 2670 (2022-03-31)BE IT ENACTED BY THE GENERAL ASSEMBLY OF THE STATE OF TENNESSEE:

SECTION 5.

(a) A public institution of higher education shall not:

(1) Conduct any mandatory training of students or employees if the training includes one (1) or more divisive concepts;

(2) Use training programs or training materials for students or employees if the program or material includes one (1) or more divisive concepts; or

(3) Use state-appropriated funds to incentivize, beyond payment of regular salary or other regular compensation, a faculty member to incorporate one (1) or more divisive concepts into academic curricula.

(b) If a public institution of higher education employs employees whose primary duties include diversity, then the duties of such employees must include efforts to strengthen and increase intellectual diversity among the students and faculty of the public institution of higher education at which they are employed.

SECTION 6.

(a) Each public institution of higher education shall conduct a biennial survey of the institution's students and employees to assess the campus climate with regard to diversity of thought and the respondents' comfort level in speaking freely on campus, regardless of political affiliation or ideology. The institution shall publish the results of the biennial survey on the institution's website.

(b) This section is repealed on July 1, 2028

CitePrintShareBill Text: TN HB2670 | 2021-2022 | 112th General Assembly | Draft. (n.d.). LegiScan. Retrieved from https://legiscan.com/TN/text/HB2670/2021

House Bill 1557 (2022) - The Florida Senate. (2022, February 28). Florida Senate. Retrieved from https://www.flsenate.gov/Session/Bill/2022/1557/?Tab=BillText

Education for American Democracy

The Better Arguments Project has developed a curriculum to help teachers facilitate a series of engaging, thought-provoking discussions that introduce students to the principles of a Better Argument and teach students how to engage productively and empathetically with diverse viewpoints. This curriculum provides structure and predictability while still allowing for modification to suit educators’ individual needs.

The Roadmap

Citizenship and American Identity Program

This teaching module helps teachers guides students to explore rare manuscripts to learn about the presidency of John F. Kennedy and his emphasis on service. After analyzing sources, students create their own calls to service.

The Roadmap

The Shapell Manuscript Foundation

This teaching module helps teachers guides students to explore rare manuscripts to learn about the presidency of John F. Kennedy and his emphasis on service. After analyzing sources, students create their own calls to service.

The Roadmap

Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media

In this lesson, students consider young people’s rationales for participating in civil rights demonstrations in Birmingham, Alabama in 1963, and the risks and rewards of their inclusion.

The Roadmap

John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum

Students explore different ways campaigns appeal to emotions to motivate their audiences to act. Students apply their understanding of positive and negative emotional appeal to a create their own campaign on the importance of exercising. Students debate the merits of positive versus negative messaging and whether one approach should be valued over the other.

The Roadmap

High Resolves

Download the Roadmap and Report

Download the Educating for American Democracy Roadmap and Report Documents

Get the Roadmap and Report to unlock the work of over 300 leading scholars, educators, practitioners, and others who spent thousands of hours preparing this robust framework and guiding principles. The time is now to prioritize history and civics.

Your contact information will not be shared, and only used to send additional updates and materials from Educating for American Democracy, from which you can unsubscribe.

We the People

This theme explores the idea of “the people” as a political concept–not just a group of people who share a landscape but a group of people who share political ideals and institutions.

Institutional & Social Transformation

This theme explores how social arrangements and conflicts have combined with political institutions to shape American life from the earliest colonial period to the present, investigates which moments of change have most defined the country, and builds understanding of how American political institutions and society changes.

Contemporary Debates & Possibilities

This theme explores the contemporary terrain of civic participation and civic agency, investigating how historical narratives shape current political arguments, how values and information shape policy arguments, and how the American people continues to renew or remake itself in pursuit of fulfillment of the promise of constitutional democracy.

Civic Participation

This theme explores the relationship between self-government and civic participation, drawing on the discipline of history to explore how citizens’ active engagement has mattered for American society and on the discipline of civics to explore the principles, values, habits, and skills that support productive engagement in a healthy, resilient constitutional democracy. This theme focuses attention on the overarching goal of engaging young people as civic participants and preparing them to assume that role successfully.

Our Changing landscapes

This theme begins from the recognition that American civic experience is tied to a particular place, and explores the history of how the United States has come to develop the physical and geographical shape it has, the complex experiences of harm and benefit which that history has delivered to different portions of the American population, and the civics questions of how political communities form in the first place, become connected to specific places, and develop membership rules. The theme also takes up the question of our contemporary responsibility to the natural world.

A New Government & Constitution

This theme explores the institutional history of the United States as well as the theoretical underpinnings of constitutional design.

A People in the World

This theme explores the place of the U.S. and the American people in a global context, investigating key historical events in international affairs,and building understanding of the principles, values, and laws at stake in debates about America’s role in the world.

The Seven Themes

The Seven Themes provide the organizational framework for the Roadmap. They map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. Importantly, they are neither standards nor curriculum, but rather a starting point for the design of standards, curricula, resources, and lessons.

Driving questions provide a glimpse into the types of inquiries that teachers can write and develop in support of in-depth civic learning. Think of them as a starting point in your curricular design.

Learn more about inquiry-based learning in the Pedagogy Companion.

Sample guiding questions are designed to foster classroom discussion, and can be starting points for one or multiple lessons. It is important to note that the sample guiding questions provided in the Roadmap are NOT an exhaustive list of questions. There are many other great topics and questions that can be explored.

Learn more about inquiry-based learning in the Pedagogy Companion.

The Seven Themes

The Seven Themes provide the organizational framework for the Roadmap. They map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. Importantly, they are neither standards nor curriculum, but rather a starting point for the design of standards, curricula, resources, and lessons.

The Five Design Challenges

America’s constitutional politics are rife with tensions and complexities. Our Design Challenges, which are arranged alongside our Themes, identify and clarify the most significant tensions that writers of standards, curricula, texts, lessons, and assessments will grapple with. In proactively recognizing and acknowledging these challenges, educators will help students better understand the complicated issues that arise in American history and civics.

Motivating Agency, Sustaining the Republic

- How can we help students understand the full context for their roles as civic participants without creating paralysis or a sense of the insignificance of their own agency in relation to the magnitude of our society, the globe, and shared challenges?

- How can we help students become engaged citizens who also sustain civil disagreement, civic friendship, and thus American constitutional democracy?

- How can we help students pursue civic action that is authentic, responsible, and informed?

America’s Plural Yet Shared Story

- How can we integrate the perspectives of Americans from all different backgrounds when narrating a history of the U.S. and explicating the content of the philosophical foundations of American constitutional democracy?

- How can we do so consistently across all historical periods and conceptual content?

- How can this more plural and more complete story of our history and foundations also be a common story, the shared inheritance of all Americans?

Simultaneously Celebrating & Critiquing Compromise

- How do we simultaneously teach the value and the danger of compromise for a free, diverse, and self-governing people?

- How do we help students make sense of the paradox that Americans continuously disagree about the ideal shape of self-government but also agree to preserve shared institutions?

Civic Honesty, Reflective Patriotism

- How can we offer an account of U.S. constitutional democracy that is simultaneously honest about the wrongs of the past without falling into cynicism, and appreciative of the founding of the United States without tipping into adulation?

Balancing the Concrete & the Abstract

- How can we support instructors in helping students move between concrete, narrative, and chronological learning and thematic and abstract or conceptual learning?

Each theme is supported by key concepts that map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. They are vertically spiraled and developed to apply to K—5 and 6—12. Importantly, they are not standards, but rather offer a vision for the integration of history and civics throughout grades K—12.

Helping Students Participate

- How can I learn to understand my role as a citizen even if I’m not old enough to take part in government? How can I get excited to solve challenges that seem too big to fix?

- How can I learn how to work together with people whose opinions are different from my own?

- How can I be inspired to want to take civic actions on my own?

America’s Shared Story

- How can I learn about the role of my culture and other cultures in American history?

- How can I see that America’s story is shared by all?

Thinking About Compromise

- How can teachers teach the good and bad sides of compromise?

- How can I make sense of Americans who believe in one government but disagree about what it should do?

Honest Patriotism

- How can I learn an honest story about America that admits failure and celebrates praise?

Balancing Time & Theme

- How can teachers help me connect historical events over time and themes?

The Six Pedagogical Principles

EAD teacher draws on six pedagogical principles that are connected sequentially.

Six Core Pedagogical Principles are part of our Pedagogy Companion. The Pedagogical Principles are designed to focus educators’ effort on techniques that best support the learning and development of student agency required of history and civic education.

EAD teachers commit to learn about and teach full and multifaceted historical and civic narratives. They appreciate student diversity and assume all students’ capacity for learning complex and rigorous content. EAD teachers focus on inclusion and equity in both content and approach as they spiral instruction across grade bands, increasing complexity and depth about relevant history and contemporary issues.

Growth Mindset and Capacity Building

EAD teachers have a growth mindset for themselves and their students, meaning that they engage in continuous self-reflection and cultivate self-knowledge. They learn and adopt content as well as practices that help all learners of diverse backgrounds reach excellence. EAD teachers need continuous and rigorous professional development (PD) and access to professional learning communities (PLCs) that offer peer support and mentoring opportunities, especially about content, pedagogical approaches, and instruction-embedded assessments.

Building an EAD-Ready Classroom and School

EAD teachers cultivate and sustain a learning environment by partnering with administrators, students, and families to conduct deep inquiry about the multifaceted stories of American constitutional democracy. They set expectations that all students know they belong and contribute to the classroom community. Students establish ownership and responsibility for their learning through mutual respect and an inclusive culture that enables students to engage courageously in rigorous discussion.

Inquiry as the Primary Mode for Learning

EAD teachers not only use the EAD Roadmap inquiry prompts as entry points to teaching full and complex content, but also cultivate students’ capacity to develop their own deep and critical inquiries about American history, civic life, and their identities and communities. They embrace these rigorous inquiries as a way to advance students’ historical and civic knowledge, and to connect that knowledge to themselves and their communities. They also help students cultivate empathy across differences and inquisitiveness to ask difficult questions, which are core to historical understanding and constructive civic participation.

Practice of Constitutional Democracy and Student Agency

EAD teachers use their content knowledge and classroom leadership to model our constitutional principle of “We the People” through democratic practices and promoting civic responsibilities, civil rights, and civic friendship in their classrooms. EAD teachers deepen students’ grasp of content and concepts by creating student opportunities to engage with real-world events and problem-solving about issues in their communities by taking informed action to create a more perfect union.

Assess, Reflect, and Improve

EAD teachers use assessments as a tool to ensure all students understand civics content and concepts and apply civics skills and agency. Students have the opportunity to reflect on their learning and give feedback to their teachers in higher-order thinking exercises that enhance as well as measure learning. EAD teachers analyze and utilize feedback and assessment for self-reflection and improving instruction.

EAD teachers commit to learn about and teach full and multifaceted historical and civic narratives. They appreciate student diversity and assume all students’ capacity for learning complex and rigorous content. EAD teachers focus on inclusion and equity in both content and approach as they spiral instruction across grade bands, increasing complexity and depth about relevant history and contemporary issues.

Growth Mindset and Capacity Building

EAD teachers have a growth mindset for themselves and their students, meaning that they engage in continuous self-reflection and cultivate self-knowledge. They learn and adopt content as well as practices that help all learners of diverse backgrounds reach excellence. EAD teachers need continuous and rigorous professional development (PD) and access to professional learning communities (PLCs) that offer peer support and mentoring opportunities, especially about content, pedagogical approaches, and instruction-embedded assessments.

Building an EAD-Ready Classroom and School

EAD teachers cultivate and sustain a learning environment by partnering with administrators, students, and families to conduct deep inquiry about the multifaceted stories of American constitutional democracy. They set expectations that all students know they belong and contribute to the classroom community. Students establish ownership and responsibility for their learning through mutual respect and an inclusive culture that enables students to engage courageously in rigorous discussion.

Inquiry as the Primary Mode for Learning

EAD teachers not only use the EAD Roadmap inquiry prompts as entry points to teaching full and complex content, but also cultivate students’ capacity to develop their own deep and critical inquiries about American history, civic life, and their identities and communities. They embrace these rigorous inquiries as a way to advance students’ historical and civic knowledge, and to connect that knowledge to themselves and their communities. They also help students cultivate empathy across differences and inquisitiveness to ask difficult questions, which are core to historical understanding and constructive civic participation.

Practice of Constitutional Democracy and Student Agency

EAD teachers use their content knowledge and classroom leadership to model our constitutional principle of “We the People” through democratic practices and promoting civic responsibilities, civil rights, and civic friendship in their classrooms. EAD teachers deepen students’ grasp of content and concepts by creating student opportunities to engage with real-world events and problem-solving about issues in their communities by taking informed action to create a more perfect union.

Assess, Reflect, and Improve

EAD teachers use assessments as a tool to ensure all students understand civics content and concepts and apply civics skills and agency. Students have the opportunity to reflect on their learning and give feedback to their teachers in higher-order thinking exercises that enhance as well as measure learning. EAD teachers analyze and utilize feedback and assessment for self-reflection and improving instruction.

![Village of Skokie v. National Socialist Party of America [photographs,1978]](/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/In-Village-of-Skokie-v.-National-Socialist-Party-1024x682.jpg)

![Village of Skokie v. National Socialist Party of America [photographs,1978]](/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/In-Village-of-Skokie-v.-National-Socialist-Party-2-1024x678.jpg)

![Village of Skokie v. National Socialist Party of America [photographs,1978]](/wp-content/uploads/2023/09/In-Village-of-Skokie-v.-National-Socialist-Party-3.jpg)