The curated resources linked below are an initial sample of the resources coming from a collaborative and rigorous review process with the EAD Content Curation Task Force.

Reset All

Reset All

In this lesson plan, students will read, view, and discuss child labor before reforms were made in our country.

The Roadmap

Alabama Department of Archives and History

On the occasion of the launch of the Mandela Children’s Fund, Nelson Mandela said, “There can be no keener revelation of a society's soul than the way in which it treats its children.” Children have often been caught up and played a role in the ideological and political movements that have taken place throughout U.S. History. What can we learn about these political and ideological movements through the lens of children and their experiences? When we frame our study of the past through the experiences of children and adolescents, we create pathways for connection and curiosity for our students. There are many ways you might use these sources in your curriculum. Use these sources individually, as you cover a particular era, or collectively, as students examine change and continuity in the experiences of children and teens over time. Sources are indexed below by theme and era and each source includes a brief description as well as guiding questions for use in the classroom.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by SubthemeEducation and its Impact on Children and Teens (12)Children and Public Activism (7)

- Primary Resources by Era/DateColonial Era (3)Nineteenth Century (3)1930s - 1940s (3)1940s, 50s, and 60s (9)Early Twentieth Century and WWI (6)

- All 24 Primary ResourcesContract for the Indenture of Elizabeth Fortune, Aged 9, 1723Contract for the Indenture of Elizabeth Fortune, Aged 9, 1723Transcript

John Fortune and Maria his wife have by these presents put, placed, and bound their daughter Elizabeth Fortune aged nine years the first day of March last past as an apprentice with the Said Elizabeth Sharpas

as an apprentice with her, the said Elizabeth Sharpas, to dwell from the day of the date of these presents for and during the term of Nine Years…The Said Elizabeth Fortune unto according to her power, wit, and ability and honestly and obediently in all things shall behave herself towards her said Mistress and all hers and shall not contract matrimony during the said Term.

Elizabeth Sharpas for her part promises, Covenants, agrees that she the said Elizabeth Sharpas apprenticed Elizabeth Fortune in the art and skill of housewifery.

This document provides a glimpse into the experiences of colonial children who spent much of their childhood working for families that were not their own. This indenture arraignment also highlights the kinds of skills and education that were valued for girls. Namely, Elizabeth Fortune is said to receive training in the “art of housewifery” in exchange for her service.

CitePrintShare“Indenture of Elizabeth Fortune, September 10, 1723,” Women & the American Story, https://wams.nyhistory.org/settler-colonialism-and-revolution/settler-colonialism/children-at-work/#. Accessed 1 April 2022.

Needlework by Sarah Anne Janeway, 1783 - Training for domestic workSewn Sampler made by 11-year-old Sarah Anne Janeway, 1783Young colonial girls raised in wealthy households were trained in the skills of a housewife early on. Samplers like this one displayed a girl's aptitude for needlework and could be hung as a piece of art in a family household.

CitePrintShare“Symbols of Accomplishment - Women & the American Story.” Women & the American Story, https://wams.nyhistory.org/settler-colonialism-and-revolution/settler-colonialism/symbols-of-accomplishment/#. Accessed 1 April 2022.

A New England Primer, 1803 - The role of religion in educationIn colonial New England, a primer like this one may have been in use as early as 1690. Children first learned their ABCs and basic literacy through primers. Since the Bible was seen as the primary means through which a child would attain literacy, these primers would often incorporate religious themes and morals.

CitePrintShareWestminster Assembly. “The New-England primer,” Boston: Printed for and sold by A. Ellison, in Seven-Star Lane, 1773. Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/22023945/>. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Perry Lewis (b. 1850), formerly enslaved, recounts his childhood in Baltimore, M.D. - Enslaved children and lack of access to educationPerry Lewis (b. 1850), formerly enslaved, recounts his childhood in Baltimore, M.D.TranscriptAs you know the mother was the owner of the children that she brought into the world Mother being a slave made me a slave. She cooked and worked on the farm, ate whatever was in the farmhouse and did her share of work to keep and maintain the Tolsons.

They being poor, not having a large place or a number of slaves to increase their wealth, made them little above the free colored people and with no knowledge, they could not teach me or anyone else to read…

In my childhood days, I played marbles, this was the only game I remember playing. As I was on a small farm, we did not come in contact much with other children and heard no childrens’ songs. I therefore do not recall the songs we sang.

Records from the Federal Writers Project are of immense importance in documenting and preserving the experiences of those who survived enslavement. ; Lewis’ account includes reference to the concept of hypodescent, which allowed intergenerational, chattel slavery to persist in the U.S. Lewis also makes note of his lack of access to education and some memories of his childhood.

1- Miletich, Patricia. “Religion and Literacy in Colonial New England | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History |, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/lesson-plan/religion-and-literacy-colonial-new-england. Accessed 2 April 2022.

- For more on the Federal Writer’s Project see Smith, Clint. “The Value of the Federal Writers' Project Slave Narratives.” The Atlantic, 9 February 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/03/federal-writers-project/617790/. Accessed 19 April 2022.

CitePrintShareFederal Writers' Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 8, Maryland, Brooks-Williams. 1936. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/mesn080/>. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Before and After Photos of Children enrolled in Carlilse Residential Indian School, 1890s - Residential School SystemOne of the “before-and-after-education” photographs of Sioux boys taken before arriving at boarding school in the 1890s.At Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, and other residential schools like it, Native American children and teens were required to give up their tribal traditions and culture. Carlisle opened in 1879 as the first government-run residential school, aimed at forcing Indigenous youth to assimilate to White culture. These before and after photos were taken as a way to demonstrate the efforts at assimilation.

1- “Richard Henry Pratt Carlisle Indian School.” Carlisle Indian School Project, https://carlisleindianschoolproject.com/past/. Accessed 2 April 2022.

CitePrintShareImage 1: "Sioux boys as they arrived at Carlisle," Digital Public Library of America, http://dp.la/item/d7ca78d98ae563bfefd20c2620613c8b. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Image 2: "Sioux boys 3 years after arriving at Carlisle," Digital Public Library of America, http://dp.la/item/f7b6ae7adfd4a9c9ecbceaf3af5fa8b5. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Sample Program For One Week - Residential School SystemSample daily program for one week at an Indian school, 1914Life for a student at the Carlisle Indian School was highly regimented and militaristic, signaling the government’s influence on the school’s mission and identity. This source, paired with the images above, offers a glimpse into the daily experience of those enrolled in this program as well as information about the aims of the federal government in establishing institutions such as Carlisle.

CitePrintShare“Cover letter, January 23, 1914, with attached sample daily program for one week at an Indian school”; 1/1914; Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group 75. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/cover-letter-january-23-1914-with-attached-sample-daily-program-for-one-week-at-an-indian-school. Accessed March 24, 2022.

Mary Ann Yahiro recites the Pledge of Allegiance at Raphael Weill School in San Francisco before being sent to Topaz internment camp in Utah, April 1942 - Japanese IntenmentMary Ann Yahiro, center, recites the Pledge of Allegiance at Raphael Weill School in San Francisco in April 1942 before being sent to Topaz internment camp in Utah.This photograph shows a group of children in the Weil Public School reciting the pledge of allegiance to the U.S. flag. The young girl in the front row center is Helen Mihara. A few months before this image was taken, Helen’s father, a San Francisco businessman, was arrested and detained in a Department of Justice camp for “enemy aliens.” Soon after this image was taken, Helen and her mother were placed in Tule Lake Relocation Center. Her mother later died in detention.

1- “San Francisco, Calif., April 1942 - Children of the Weill public school, from the so-called international settlement, shown in a flag pledge ceremony. Some of them are evacuees of Japanese ancestry who will be housed in War relocation authority centers for.” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2001705926/. Accessed 5 April 2022.

CitePrintShareLange, Dorothea, photographer. San Francisco, Calif., April- Children of the Weill public school, from the so-called international settlement, shown in a flag pledge ceremony. Some of them are evacuees of Japanese ancestry who will be housed in War relocation authority centers for the duration. [April] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2001705926/>. Accessed April 10, 2022.

TIME Magazine Feature on the American “teen-ager," 1944 - American Teenage Girls“The Invention of the American “teen-ager,” 1944Although it is not a certainty, some historians believe that the concept of the American “teenager” originated sometime in the 1940s. A liminal age, the teenager was neither child nor adult. This 1944 TIME Magazine article detailed the “life of the American Teenager” by photojournalist Nina Leen. The full article offers a glimpse into the perception of teens but also offers opportunities for students to consider the rise of the middle class, social status, and race in the middle of the twentieth century.

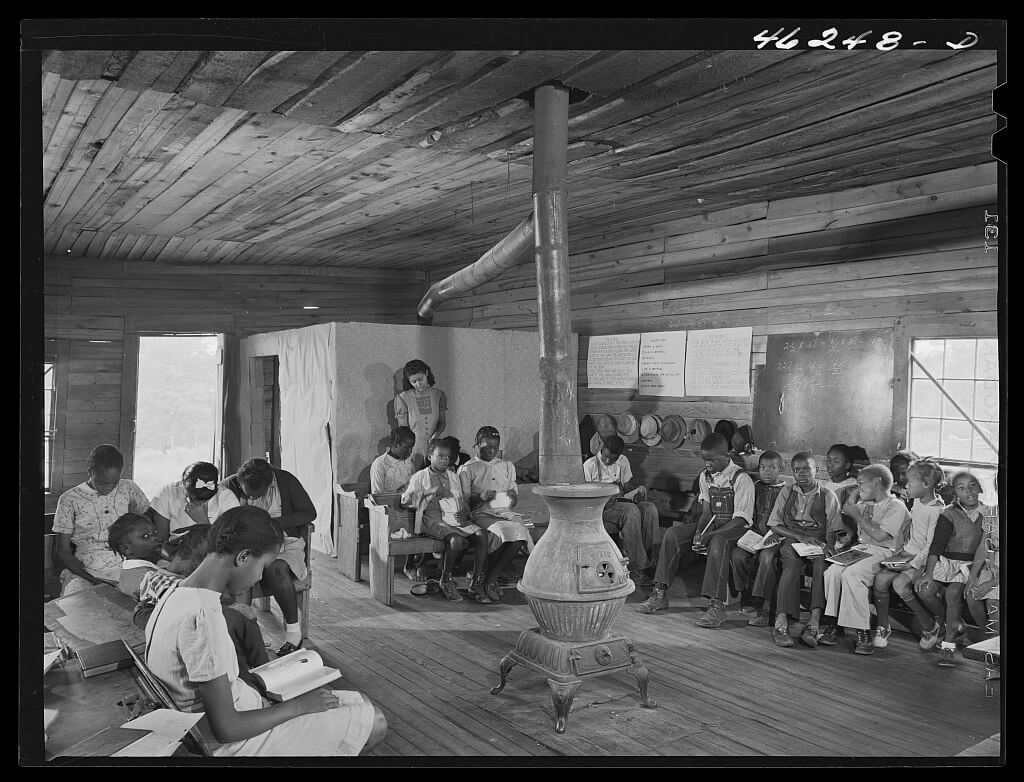

Separate but Unequal: Two classrooms before Brown v. Board of Education, Georgia, 1941 - School SegregationSchool segregation was among the most central concerns of the Civil Rights Movement since the 1930s. Activists for school integration argued that separate was not equal and every child, regardless of race, was entitled to education in a safe learning environment. These two images depict daily life in segregated classrooms in the same year, 1941. Brown v. Board of Education would not be passed for more than a decade.

1- “Recovery Programs.” Recovery Programs | DPLA, https://dp.la/exhibitions/new-deal/recovery-programs/farm-security-administration?item=409. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareImage 1: Delano, J., photographer. (1941) Veazy, Greene County, Georgia. The one-teacher Negro school in Veazy, south of Greensboro. United States Greene County Georgia Veazy, 1941. Oct. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017796657/. Accessed April 10, 2022.

Image 2: Delano, J., photographer. (1941) Siloam, Greene County, Georgia. Classroom in the school. United States Greene County Siloam Georgia, 1941. Oct. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017796554/. Accessed April 10, 2022.

Telegram from Parents of the Little Rock Nine to President Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1957-58 - School IntegrationTelegram from Parents of the Little Rock Nine to President Dwight D. EisenhowerWritten three years after the passage of Brown v. Board of Education, this telegram to President Eisenhower details the feelings of parents of the Little Rock Nine, who were a part of the busing program to integrate the Little Rock school system. The Little Rock Nine were the first African American students to enter Little Rock’s Central High School in Arkansas. The parents note that because of the supreme court ruling their “faith in democracy” had been renewed.

1- “The Little Rock Nine.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/little-rock-nine. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareTelegram from Parents of the Little Rock Nine to President Dwight D. Eisenhower; 10/1957; OF 142-A-5 Negro Matters - Colored Question (5), 1957 - 1958; Official Files, 1953 - 1961; Collection DDE-WHCF: White House Central Files (Eisenhower Administration), 1953 - 1961; Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Abilene, KS. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/telegram-parents-little-rock-nine-to-president-eisenhower. Accessed April 1, 2022.

African American children on their way to PS204, 82nd Street, and 15th Avenue, pass mothers protesting the busing of children to achieve integration, 1965 - School IntegrationAfrican American children on their way to PS204, 82nd Street, and 15th Avenue, pass mothers protesting the busing of children to achieve integrationEven after the passage of Brown v. Board of Education, school integration was protested. This image shows African American children entering their new school while white mothers protest school integration

CitePrintShareDemarsico, Dick, photographer. African American children on way to PS204, 82nd Street and 15th Avenue, pass mothers protesting the busing of children to achieve integration (1965). Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2004670162/>. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Audio Recording: Conversation with 11 and 12-year-old black females, Meadville, Mississippi, 1973 - Daily life for two pre-teens in DetriotThis conversation was originally recorded as part of an effort to archive regional dialects by the Library of Congress. It also provides a glimpse into the daily lives of pre-teen girls, including racial discrimination they faced in their school community.

Audio Recording: Conversation with 11 and 12-year-old black females, Meadville, Mississippi

CitePrintShareUnidentified, and Walt Wolfram. Conversation with 11 and 12-year-old black females, Meadville, Mississippi. to 1973, 1972. Audio. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/afccal000213/>. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Mother Jones and Children Laborers go on Strike, 1903Mother Jones and Children Laborers go on Strike, 1903In July of 1903, Mother Jones led a march from Philadelphia to the home of President Rosevelt to protest the unsafe labor conditions of children working in mills. The story of Mother Jones and the children who accompanied her on her march showcases not only youth activism but also women in the labor movement at the turn of the century.

1- Lauren Cooper. “July 7, 1903: March of the Mill Children.” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/mother-jones-march-mill-children/. Accessed 3 April 2022.

CitePrintShare"Mother" Jones and her army of striking textile workers starting out for their descent on New York The textile workers of Philadelphia say they intend to show the people of the country their condition by marching through all the important cities”; 1903; Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2015649893/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Child Labor Standards, 1916Child Labor StandardsThis ad was created after the passage of the Keating-Own Child Labor Act of 1916. This act limited the working hours of children and placed an age requirement of the age of 16 for any working child. It also forbade the interstate sale of goods produced in factories that employed child labor.

CitePrintShare"Child Labor Standards"; ca. 1941-1945; Records of the Office of War Information, Record Group 208. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/child-labor-standards. April 1, 2022.

Girl Scouts and the War EffortGirl Scout Troup Plants a Victory Garden, 1917Girl Scout Pledge Card to Save for a Soldier, 1914After the US declared war in 1917, children were encouraged to support the war efforts. The Girl Scouts of America provided an opportunity for girls to become involved in volunteer work for the war effort. Organizations like the Girls Scouts and 4H typically trained girls for domestic work. Skills like sewing and first-aid were put to use in new ways for members of the Girl Scouts and 4H during WWI. Here, scouts planted a Victory Garden. Victory gardens, or liberty gardens, first appeared during WWI. The federal government encouraged citizens to plant vegetable gardens to mitigate any food shortages that resulted from the war.

1- Lauren Cooper. “July 7, 1903: March of the Mill Children.” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/mother-jones-march-mill-children/. Accessed 3 April 2022.

- Spring, Kelly A. “Girls' Volunteer Groups during World War I.” National Women's History Museum, https://www.womenshistory.org/resources/general/girls-volunteer-groups-during-world-war-i. Accessed 3 April 2022.

CitePrintShareImage 1: Harris & Ewing, photographer. NATIONAL EMERGENCY WAR GARDENS COM. GIRL SCOUTS GARDENING AT D.A.R. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2016867777/>. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Image 2: “Girl Scout Pledge Card "To Save for a Solder”. 1914. Girl Scout Archive Management Center. https://archives.girlscouts.org/Detail/objects/64958. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Boy Scouts as Bond Workers, 1917Boy Scouts as Bond Workers, 1917Boyscouts, like Girl Scouts, volunteered in the war effort during both WWI and II. Here, scouts who were too young to go to combat sell war bonds.

CitePrintShareBain News Service, Publisher. Boy Scouts as bond workers. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2014704734/>. Accessed April 10, 2022.

12-Year-Old Girl at the March on Washington, 196312-Year-Old Girl at the March on WashingtonOn August 28, 1963, thousands took part in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The March was instigated by a continuing lack of jobs for African Americans and the persistence of segregation. The march was influential in pressuring President John F. Kennedy to draft a strong civil rights bill. This photo depicts Edith Lee-Payne on her twelfth birthday. Edith attended the March with her mother.

1- “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom | The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute.” The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute |, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/march-washington-jobs-and-freedom. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintSharePhotograph 306-SSM-4C-61-32; Young Woman at the Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. with a Banner; 8/28/1963; Miscellaneous Subjects, Staff and Stringer Photographs, 1961 - 1974; Records of the U.S. Information Agency, Record Group 306; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/girl-march-on-washington-banner. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Protests in support of the 26th Amendment, 1969Protests in support of the 26th AmendmentThe 26th Amendment to the Constitution allowed for those 18 years old or older to vote in elections. Support for decreasing the voting age from 21 to 18 increased during World War II, as young men were conscripted to fight in the war as young as 18 but could not yet vote. This image depicts youth protestors in support of the 26th amendment.

1- “The 26th Amendment | Richard Nixon Museum and Library.” Nixon Presidential Library, 17 June 2021, https://www.nixonlibrary.gov/news/26th-amendment. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShare“Demonstration for reduction in voting age, Seattle, 1969”; Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, Museum of History & Industry, Seattle; https://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/digital/collection/imlsmohai/id/1715/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Little Spinner in Globe Cotton Mill, Augusta, Ga., 1909Little Spinner in Globe Cotton Mill, Augusta, Ga., 1909Images of children laborers at the turn of the century reveal the experiences of children who spent most of their days working in the oftentimes harsh and unsafe conditions of urban factories. After the Civil War, as industry grew in urban areas, children often worked in factories, in markets, and on the streets as vendors.

Children Working in a Textile Mill in Georgia, 1909Children Working in a Textile Mill in GeorgiaLike the image above, this source shows a young child operating machinery that he is not even tall enough to reach. Images like these and the one above were captured by activists for child labor laws. The Child labor standards act would be passed in 1916

1- Schuman, Michael. “History of child labor in the United States—part 1: little children working: Monthly Labor Review: US Bureau of Labor Statistics.” Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2017/article/history-of-child-labor-in-the-united-states-part-1.htm. Accessed 19 April 2022.

CitePrintSharePhotograph 102-LH-488; Bibb Mill No. 1, Macon, Ga.; 1/19/1909; Bibb Mill No. 1, Macon, Ga. Many youngsters here. Some boys and girls were so small they had to climb up onto the spinning frame to mend broken threads and to put back the empty bobbins.,; Records of the Children's Bureau, Record Group 102; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/bibb-mill. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Spread from Look magazine on sharecropping children, 1937Page from Look magazine, 1937 on sharecropping childrenThis magazine spread on sharecropping children was published the same year that President Rosevelt established the Farm Security Administration. The FSA was a New Deal agency that provided assistance and relief to agricultural workers impacted by drought and the Great Depression.

1- “Gardening for the Common Good.” Smithsonian Libraries, https://library.si.edu/exhibition/cultivating-americas-gardens/gardening-for-the-common-good. Accessed 19 April 2022.

CitePrintSharePages 18 and 19 of March Look magazine. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2017760274/>. April Accessed April 10, 2022.

Boys playing marbles, Farm Security Administration labor camp, Robstown, Texas, 1944Boys playing marbles, Farm Security Administration labor camp, Robstown, Texas, 1944During the Great Depression, The Farm Security Administration attempted to aid workers and farmers by setting up housing camps, providing loans and training to workers, among other forms of assistance. This source shows a group of children playing marbles in one of the FSA labor camps in Texas, offering a glimpse into daily life and play for children living through the Great Depression.

CitePrintShareRothstein, A., photographer. (1942) Boys playing marbles, FSA ... labor camp, Robstown, Texas. United States Robstown Texas, 1942. Jan. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017877649/. Accessed April 10, 2022.

School Closures during Little Rock Nine: Girls learn from Home, 1958 - School IntegrationSchool Closures during Little Rock 9: three pajama-clad white girls being educated via television during the period that the Little Rock schools were closed to avoid integration.In September 1958, Governor Faubus of Arkansas closed all Little Rock public high schools as a result of unrest due to integration. Known as the “Lost Year,” both teachers and students were blocked from their school buildings. This image shows three girls learning “remotely” during that time and offers a glimpse of the efforts to maintain continuity of education in the midst of upheaval.

1- “The Little Rock Nine.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/little-rock-nine. Accessed 4 April 2022.

- “Sept. 12, 1958: Little Rock Public Schools Closed.” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/little-rock-schools-closed/. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareO'Halloran, T. J., photographer. (1958) Little Rock, Ark. Attempts to reopen schools / TOH. Arkansas Little Rock, 1958. Sept. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003654390/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Letter from Linda Kelly, Sherry Bane, and Mickie Mattson to President Dwight D. Eisenhower Regarding Elvis Presley, 1953-1961Letter from Linda Kelly, Sherry Bane, and Mickie Mattson to President Dwight D. Eisenhower Regarding Elvis Presley, 1953-1961Celebrities were no exception to the draft during the Vietnam War. Elvis Presley joined the army in 1958 and, in this letter, three girls from Nevada ask President Eisenhower not to shave off his sideburns. This source offers a window into the lives of American teens as well as an example of the role teens played in the evolution and development of American pop culture.

1- Cosgrove, Ben. “The Invention of Teenagers: LIFE and the Triumph of Youth Culture.” Time.com, TIME, 28 September 2013, https://time.com/3639041/the-invention-of-teenagers-life-and-the-triumph-of-youth-culture/. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareBane, Sherry Author, Linda Author Kelly, and Mickie Author Mattson. Letter from Linda Kelly, Sherry Bane, and Mickie Mattson to President Dwight D. Eisenhower Regarding Elvis Presley. [Place of Publication Not Identified: Publisher Not Identified, 1958] Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2021667581/> Accessed April 4, 2022.

- Additional Resources

- Teacher's Guides and Analysis Tool | Getting Started with Primary Sources | Teachers | Programs | Library of Congress

- Document Analysis Overview | National Archives

- Activity Tools | DocsTeach

- Primary Source Activity Guide | EAD Team

Education for American Democracy

In this lesson, students explore ideas about citizenship, power, and responsibility by listening to and discussing a podcast featuring an interview with Eric Liu, the founder and CEO of Citizen University, to deepen their understanding of citizen power.

The Roadmap

Facing History and Ourselves

Students learn the basic steps of civic action and what it takes to make change, following the "I AM" model (Inform, Act, Maintain). Along the way, they explore the change-making examples of four key movements: women's rights, disability awareness, Native American rights, and migrant farm worker rights.

The Roadmap

iCivics, Inc.

Eagle Eye Citizen allows teachers and students to solve or create online interactive challenges while engaging with rich Library of Congress primary sources. Students learn civics content as well as primary source analysis skills.

The Roadmap

Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media

This lesson helps students gain a more nuanced perspective on the Progressive Era through close reading of primary documents and group presentations of particular readings in the style of a living newspaper.

The Roadmap

Facing History and Ourselves

Learn how activists in Louisville, Kentucky successfully campaigned against segregated streetcars in 1870-71.

The Roadmap

Learning for Justice

This set of Library of Congress primary sources explores systems of racial segregation in the U.S. and the efforts of African American civil rights movements to end them.

The Roadmap

The Library of Congress

This teaching module helps teachers guides students to explore rare manuscripts to learn about the presidency of John F. Kennedy and his emphasis on service. After analyzing sources, students create their own calls to service.

The Roadmap

The Shapell Manuscript Foundation

This teaching module helps teachers guides students to explore rare manuscripts to learn about the presidency of John F. Kennedy and his emphasis on service. After analyzing sources, students create their own calls to service.

The Roadmap

Roy Rosenzweig Center for History and New Media

In this lesson, students analyze benchmarks developed by political scientists to measure the health of democracy in the United States.

The Roadmap

Facing History and Ourselves

Students analyze Martin Luther King Jr.’s “Letter From Birmingham Jail” to understand his vision for the civil rights movement. Students read King's letter and "A Call for Unity" (which prompted King's response) before engaging in a classroom discussion about civil rights, justice, nonviolence, and more.

The Roadmap

NewseumED