The curated resources linked below are an initial sample of the resources coming from a collaborative and rigorous review process with the EAD Content Curation Task Force.

Reset All

Reset All

What does it mean to be a good citizen? Students investigate this question by looking at the Naturalization Oath of Allegiance, which foreign-born people must take to become naturalized American citizens, and thinking deeply about what are or should be crucial requirements of citizenship. This lesson guides students to closely examine information, to ask probing questions, and to take part in complex discussions with classmates.

The Roadmap

Smithsonian National Museum of American History

The promises of equal rights in the Declaration of Independence and of political peoplehood in the Constitution were not granted to Black women throughout much of American history. Black women were brought to the colonies violently in the slave trade, or born into slavery in North America. Most were deprived of all freedoms as enslaved people. Black women were first entirely denied access to education, and then to equal access. They were disenfranchised, even when Black men and white women were ultimately granted the right to vote. Nonetheless, the voices of Black women resonate throughout American history in letters, speeches, personal narratives, court cases, journalism, higher institutions of learning, and political leadership. In all eras of American history, Black women use their voices to fight for the rights they were denied and to dismantle the legal, political, and philosophical barriers that stood in their way.

This Spotlight Kit features the voices of Black women who paved the way for the election of Kamala Harris as the nation’s first Black and Asian American Vice President and Ketanji Brown Jackson as the first Black woman on the Supreme Court.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by Era/Date1773 (1)1781 (1)1833 (1)1851 (1)1848 (1)1891 (1)1892 (1)1898 (1)1915 (1)1920 (1)1955 (2)1962 (1)1964 (1)1968 (2)1970 (1)1971 (1)2001 (1)

- All 19 Primary ResourcesPhillis Wheatley by an unidentified artist, Engraving on paper (1773)National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution

The National Portrait Gallery describes the singular achievement of Phillis Wheatley: “In 1773, Phillis Wheatley accomplished something that no other woman of her status had done. When her book of poetry, Poems on Various Subjects, Religious and Moral, appeared, she became the first American slave, the first person of African descent, and only the third colonial American woman to have her work published.”

CitePrintShare“Phillis Wheatley: Her Life, Poetry, and Legacy | National Portrait Gallery.” National Portrait Gallery, https://npg.si.edu/blog/phillis-wheatley-her-life-poetry-and-legacy.

Brom & Bett vs. J. Ashley Esq. (1781)“Mumbet,” who later took the name Elizabeth Freeman, was an enslaved woman given by one man, Pieter Hogeboom, to another, Colonel John Ashley, when Ashley married Hogeboom’s daughter in Massachusetts.

Mumbet sued for her freedom in 1781. “According to historian Arthur Zilversmit the people of Berkshire County then adopted Mumbet’s cause to test the constitutionality of slavery following the passage of the new state constitution. ‘Brom and Bett’ were the first enslaved African Americans to be set free under the new Massachusetts State Constitution of 1780.”

Court Records, Berkshire County Courthouse Great Barrington, Massachusetts Inferior Court of Common Pleas May 28, 1781 Volume 4A, page 55, NumberBrom & Bett vs. J. Ashley Esq.

“…After a full hearing of this case the evidence therein being produced, the same case is committed to the Jury Jonathan Holcom Foreman and his fellows who being duly sworn return this verdict that in this case the Jury find that the aforesaid Brom & Bett are not and were not at the time of the purchase of the original writ the legal Negro servants of him the said John Ashley during their life and [assess] thirty shillings damages wherefore it is considered by the Court Adjudged and determined that the said Brom & Bett are not, nor were they at the time of the purchase of the original writ the legal Negro of the said John Ashley during life, and that the said Brom & Bett do recover against the said John Ashley the sum of thirty shillings lawful silver Money, Damages…”

CitePrintShare“Mumbet Court Records – Elizabeth Freeman.” Elizabeth Freeman, https://elizabethfreeman.mumbet.com/who-is-mumbet/mumbet-court-records/.

Maria W. Stewart, “An Address at the African Masonic Hall” (1833)Maria W. Stewart, “An Address at the African Masonic Hall” (1833)Transcript...Our condition as a people has been low for hundreds of years, and it will continue to be so, unless, by the true piety and virtue we strive, to regain that which we have lost. White Americans, by their prudence, economy and exertions, have sprung up and become one of the most flourishing nations in the world, distinguished for their knowledge of the arts and sciences, for their polite literature. Whilst our minds are vacant and starving for want of knowledge, theirs are filled to overflowing. Most of our color have been taught to stand in fear of the white man from their earliest infancy, to work as soon as they could walk, and call ‘master’ before they scarce could lisp the name of mother. Continual fear and laborious servitude have in some degree lessened in us that natural force and energy which belong to man; or else, in defiance of opposition, our men, before this would have nobly and boldly contended for their rights. But give the man of color an equal opportunity with the white, from the cradle to manhood, and from manhood to the grave, and you would discover the dignified statesman, the man of science, and the philosopher. But there is no such opportunity for the sons of Africa, and I fear that our powerful ones are fully determined that there never shall be. Forbid, ye Powers on High, that it should any longer be said that our men possess no force. 0 ye sons of Africa, when will your voices be heard in our legislative halls, in defiance of your enemies, contending for equal rights and liberty?

According to the National Park Service’s biography of Maria Stewart, “Abolitionist and women's rights advocate Maria W. Stewart was one of the first women of any race to speak in public in the United States. She was also the first Black American woman to write and publish a political manifesto. Her calls for Black people to resist slavery, oppression, and exploitation were radical. Stewart's thinking and speaking style influenced Frederick Douglass, Sojourner Truth, and Frances Ellen Watkins Harper.”

CitePrintShare“(1833) Maria W. Stewart, "An Address at the African Masonic Hall" •.” Blackpast, 24 October 2011, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/1833-maria-w-stewart-address-african-masonic-hall/.

“Maria W. Stewart (U.S.” National Park Service, 16 January 2023, https://www.nps.gov/people/maria-w-stewart.htm.

The Anti-Slavery Bugle, Sojourner Truth at the Women’s Rights Convention (1851)Born into slavery in New York in 1797, Sojourner Truth (originally Isabella Bomfree) escaped to an abolitionist family that helped her secure her freedom. An activist for abolitionism, civil and women’s rights, Truth fought against sexism in the abolitionist movement and racism in the women’s movement. The original “Ain’t I A Woman” speech by Sojourner Truth was transcribed by Marius Robinson, a journalist who was in the audience at the Woman's Rights Convention in Akron, Ohio, on May 29, 1851.

“One of the most unique and interesting speeches at the convention was made by Sojourner Truth, an emancipated slave….she came forward to the platform and addressing the President said with great simplicity:‘...I want to say a few words about this matter. I am a woman’s rights. I have as much muscle as any man, and can do as much work as any man. I have plowed and reaped and husked and chopped and mowed, and can any man do more than that? I am as strong as any man that is now. As for intellect, all I can say is, if woman have a pint and man a quart–why can’t she have her little pint full? You need not be afraid to give us our rights for fear we will take too much, –for we can’t take more than our pint’ll hold. The poor men seem to be all in confusion, and don’t know what to do. Why children, if you have woman’s rights and you give it to her and you will feel better….’”

CitePrintShareAnti-slavery bugle. (New-Lisbon, Ohio), 21 June 1851. Chronicling America: Historic American Newspapers. Lib. of Congress. https://chroniclingamerica.loc.gov/lccn/sn83035487/1851-06-21/ed-1/seq-4/

Susie King Taylor: Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops Late 1st S. C. VolunteersSusie King Taylor escaped slavery, became a teacher at age 14, and served as a Civil War nurse for more than four years, working alongside Clara Barton. Taylor was the only Black woman to publish a memoir of her Civil War experiences.

[In Camp Saxton, 1863]“I taught a great many of the comrades in Company E to read and write, when they were off duty. Nearly all were anxious to learn. My husband taught some also when it was convenient for him. I was very happy to know my efforts were successful in camp, and also felt grateful for the appreciation of my services. I gave my services willingly for four years and three months without receiving a dollar. I was glad, however, to be allowed to go with the regiment, to care for the sick and afflicted comrades.” (21)

“While the fighting was on, a friend, Lizzie Lancaster, and I stopped at several of the rebel homes, and after talking with some of the women and children we asked them if they had any food. They claimed to have only some hard-tack, and evidently did not care to give us anything to eat, but this was not surprising. They were bitterly against our people and had no mercy or sympathy for us.

The second day, our boys were reinforced by a regiment of white soldiers, a Maine regiment, and by cavalry, and had quite a fight. On the third day, Edward Herron, who was a fine gunner on the steamer John Adams, came on shore, bringing a small cannon, which the men pulled along for more than five miles. This cannon was the only piece for shelling. On coming upon the enemy, all secured their places, and they had a lively fight, which lasted several hours, and our boys were nearly captured by the Confederates; but the Union boys carried out all their plans that day, and succeeded in driving the enemy back. After this skirmish, every afternoon between four and five o'clock the Confederate General Finegan would send a flag of truce to Colonel Higginson, warning him to send all women and children out of the city, and threatening to bombard it if this was not done.” (23-24)

“I learned to handle a musket very well while in the regiment, and could shoot straight and often hit the target. I assisted in cleaning the guns and used to fire them off, to see if the cartridges were dry, before cleaning and reloading, each day. I thought this great fun. I was also able to take a gun all apart, and put it together again.” (27)

CitePrintShareReminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops Late 1st S. C. Volunteers: Electronic Edition. Taylor, Susie King, b. 1848 https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/taylorsu/tayhttps://www.gutenberg.org/files/14975/14975-h/14975-h.htmlorsu.html

Frances E.W. Harper, Sketches of Southern Life (1891)Born free in Maryland in 1825, Frances E.W. Harper spent her life as a poet, an abolitionist, and a champion of women’s rights. She also helped enslaved people escape through the Underground Railroad, and she published several novels in addition to her poetry. Like many of the women featured in this Spotlight Kit, her writing explored the intersectionality of race, class, and gender.

AUNT CHLOE (excerpt)

I remember, well remember, That dark and dreadful day, When they whispered to me, “Chloe, Your children’s sold away!”It seemed as if a bullet Had shot me through and through, And I felt as if my heart-strings Was breaking right in two.

And I says to cousin Milly, “There must be some mistake; Where’s Mistus?” “In the great house crying— Crying like her heart would break.

“And the lawyer’s there with Mistus; Says he’s come to ’ministrate, ’Cause when master died he just left Heap of debt on the estate.

“And I thought ’twould do you good To bid your boys good-bye— To kiss them both and shake their hands, And have a hearty cry.

“Oh! Chloe, I knows how you feel, ’Cause I’se been through it all; I thought my poor old heart would break, When master sold my Saul.”

CitePrintShareHarper, Frances Ellen Watkins. “Sketches of Southern Life.” The Project Gutenberg eBook of Sketches of Southern Life, by Frances E. Watkins Harper, www.gutenberg.org/cache/epub/69249/pg69249-images.html.

Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1892)Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases, Ida B. Wells-Barnett (1892)TranscriptFrom this exposition of the race issue in lynch law, the whole matter is explained by the well-known opposition growing out of slavery to the progress of the race. This is crystalized in the oft-repeated slogan: ‘This is a white man's country and the white man must rule.’ The South resented giving the Afro-American his freedom, the ballot box and the Civil Rights Law. The raids of the Ku-Klux and White Liners to subvert reconstruction government, the Hamburg and Ellerton, S.C., the Copiah County, Miss., and the Layfayette Parish, La., massacres were excused as the natural resentment of intelligence against government by ignorance….

One by one the Southern States have legally(?) disfranchised the Afro-American, and since the repeal of the Civil Rights Bill nearly every Southern State has passed separate car laws with a penalty against their infringement. The race regardless of advancement is penned into filthy, stifling partitions cut off from smoking cars. All this while, although the political cause has been removed, the butcheries of black men at Barnwell, S.C., Carrolton, Miss., Waycross, Ga., and Memphis, Tenn., have gone on; also the flaying alive of a man in Kentucky, the burning of one in Arkansas, the hanging of a fifteen-year-old girl in Louisiana, a woman in Jackson, Tenn., and one in Hollendale, Miss., until the dark and bloody record of the South shows 728 Afro-Americans lynched during the past eight years. Not fifty of these were for political causes; the rest were for all manner of accusations from that of rape of white women, to the case of the boy Will Lewis who was hanged at Tullahoma, Tenn., last year for being drunk and ‘sassy’ to white folks.

These statistics compiled by the Chicago Tribune were given the first of this year (1892). Since then, not less than one hundred and fifty have been known to have met violent death at the hands of cruel bloodthirsty mobs during the past nine months.

Ida B. Wells-Barnett was an outspoken activist for many causes. In 1884, she sued a train company for wrongfully removing her from a first-class train for which she had purchased a ticket. Throughout the 1880s and 1890s, she used her work as a journalist to investigate and expose the lynching of Black men and women, including the publication of this document. She also fought for women’s suffrage, even marching with the movement over the objections of some white participants who did not want Black women to participate.

CitePrintShare“Southern Horrors: Lynch Law in All Its Phases.” The Project Gutenberg eBook of Southern Horrors: Lynch Law In All Its Phases, by Ida B. Wells-Barnett., www.gutenberg.org/files/14975/14975-h/14975-h.htm.

General Affidavit of Harriet Tubman Davis regarding payment for services rendered during the Civil War (1898)According to the National Women’s History Museum and historian Debra Michals, “Harriet Tubman was enslaved, escaped, and helped others gain their freedom as a ‘conductor’ of the Underground Railroad. Tubman also served as a scout, spy, guerrilla soldier, and nurse for the Union Army during the Civil War. She is considered the first African American woman to serve in the military.” In this document, Tubman petitioned for back pay for her services to the military, ultimately securing a pension of $8 a month as the widow of a Union soldier and $20 for her service. When she died, she was buried with military honors.

CitePrintSharePage 1 of General Affidavit of Harriet Tubman Davis regarding payment for services rendered during the Civil War, c. 1898, RG 233, Records of the U.S. House of Representatives, National Archives https://www.archives.gov/legislative/features/claim-of-harriet-tubman

Michals, Debra. “Harriet Tubman Biography.” National Women's History Museum, https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/harriet-tubman.

Woman Suffrage and the 15th Amendment, Mary Church Terrell in The Crisis (1915)The Crisis was the official magazine of the NAACP, and this issue from 1915 was dedicated to the issue of women’s suffrage. Mary Church Terrell’s activism began with her involvement in Ida B. Wells-Barnett’s anti-lynching movement, following the death by lynching of a friend in Memphis. As the founder of the National Association for Colored Women (NACW), she fought for Black women’s suffrage specifically (and for women’s suffrage broadly) as the key to ultimate equality.

CitePrintShare“The Crisis, Vol. 10, No. 4.” Brown University Library, library.brown.edu/pdfs/128895937640750.pdf.

“A Philosophy of Education for Negro Girls” Mary McLeod Bethune (1920)Literary and Industrial Training School for Negro Girls, Daytona FL (1920)Transcript...If there is to be any distinctive difference between the education of the Negro girl and the Negro boy, it should be that of consideration for the unique responsibility of this girl in the world today. The challenge to the Negro home is one which dares the Negro to develop initiative to solve his own problem, to work out his own problems, to work out his difficulties in a superior fashion, and to finally come into his right as an American Citizen, because he is tolerated. This is the moral responsibility of the education of the Negro girl; It must become a part of her thinking; her activities must lead her into such endeavors early in her educational life; this training must be inculcated into the school curricula so that the result may be a natural expression — born into her children. Such is the natural endowment which her education must make it possible for her to bequeath to the future of the Negro race.

The education of the Negro girl must embrace a larger appreciation for good citizenship in the home. Our girls must be taught cleanliness, beauty and thoughtfulness and their application in making home life possible. For proper home life provides the proper atmosphere for life everywhere else. The ideas of home must not forever be talked about; they must be living factors built into the everyday educational experiences of our girls.

Negro girls must receive also a peculiar appreciation for the expression of the creative self. They must be taught to realize their responsibility to find ways whereby the home and the schoolroom may encourage our youth to be creative; to develop to the fullest extent the inner urges that make them distinctive and that will lead them to be worthy contributors to the life of the little worlds in which they will live. This in itself will do more to remove the walls of inter-racial prejudice and build up intra-racial confidence and pride than many of our educational tools and devices.

Mary McLeod-Bethune was one of seventeen children, raised in part working in the fields of the plantation where her parents had been formerly enslaved. She became a prominent educator. The school for girls, pictured and described here, ultimately merged with the all-male Cookman Institute and in 1929 became Bethune-Cookman College.

CitePrintShare“Florida Memory • Primary Source Set: Mary McLeod Bethune.” Florida Memory, State Library and Archives of Florida. www.floridamemory.com/items/show/341521.

McLeod Bethune, Mary. "A Philosophy of Education for Negro Girls." Speaking While Female Speech Bank, 1920, https://speakingwhilefemale.co/education-bethune/.

Fingerprint Card of Rosa Parks Civil Case 1147 Browder, et al. v. Gayle, et al (1955)Fingerprint Card of Rosa Parks Civil Case 1147 Browder, et al. v. Gayle, et al (1955)Transcript“People always say that I didn’t give up my seat because I was tired, but that isn’t true. I was not tired physically, or no more tired than I usually was at the end of a working day. I was not old, although some people have an image of me as being old then. I was forty-two. No, the only tired I was, was tired of giving in.”

(from her 1992 autobiography)

Although Rosa Parks is well known as the woman whose actions initiated the Montgomery Bus Boycott in 1955, her story is misunderstood and mischaracterized. As historian Stephanie Townrow explains, “Rosa Parks had been an activist for civil rights most of her life, and was an active member of the Montgomery NAACP chapter. In her 1992 autobiography, Parks challenged the simplistic narrative that she was just too tired after a long day’s work to give up her seat.” A passage from Parks’ autobiography is cited here, along with the fingerprinting card from the arrest that followed her refusal to move.

CitePrintShareFingerprint Card of Rosa Parks Civil Case 1147 Browder, et al. v. Gayle, et al.; U.S. District Court for Middle District of Alabama, Northern (Montgomery) Division Record Group 21: Records of the District Court of the United States National Archives and Records Administration-Southeast Region, East Point, GA. https://www.archives.gov/education/lessons/rosa-parks

Quote: Townrow, Stephanie. “Rosa Parks Refuses to Move: On This Day, December 1 | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History |, 1 December 2015, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/news/rosa-parks-refuses-move-day-december-1.

Zora Neale Hurston’s Letter to The Orlando Sentinel (1955)Zora Neale Hurston’s Letter to The Orlando Sentinel (August 11, 1955)TranscriptEditor: I promised God and some other responsible characters, including a bench of bishops, that I was not going to part my lips concerning the U.S. Supreme Court decision on ending segregation in the public schools of the South. But since a lot of time has passed and no one seems to touch on what to me appears to be the most important point in the hassle, I break my silence just this once. Consider me as just thinking out loud.

The whole matter revolves around the self-respect of my people. How much satisfaction can I get from a court order for somebody to associate with me who does not wish me near them? The American Indian has never been spoken of as a minority and chiefly because there is no whine in the Indian. Certainly he fought, and valiantly for his lands, and rightfully so, but it is inconceivable of an Indian to seek forcible association with anyone. His well known pride and self-respect would save him from that. I take the Indian position….

…If there are not adequate Negro schools in Florida, and there is some residual, some inherent and unchangeable quality in white schools, impossible to duplicate anywhere else, then I am the first to insist that Negro children of Florida be allowed to share this boon. But if there are adequate Negro schools and prepared instructors and instructions, then there is nothing different except the presence of white people.

For this reason, I regard the ruling of the U.S. Supreme Court as insulting rather than honoring my race….

Zora Neale Hurston is most famous as an anthropologist and novelist. She wove Black folklore, linguistics, and culture into her writing, including the collection Mules and Men and the novel Their Eyes Were Watching God. In this letter, she expresses controversial opposition to the Supreme Court ruling in Brown v. the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas.

CitePrintShare“(1955) Zora Neale Hurston's Letter to the Orlando Sentinel •.” Blackpast, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/zora-neale-hurston-s-letter-orlando-sentinel-1955/.

Constance Baker Motley, interview with The Visionary Project, “My Inspiration to Be a Lawyer”TranscriptConstance Baker Motley with James Meredith and lawyer Jack Greenberg after a 1962 appellate court hearing in New Orleans. Credit: Library of Congress, Prints and Photographs Division, NYWT&S Collection, LC-DIG-ppmsca-05544.

Constance Baker Motley, interview with The Visionary Project, “My Inspiration to Be a Lawyer” (excerpt, video)

Constance Baker Motley was the first Black woman to argue at the Supreme Court and argued ten landmark civil rights cases, winning nine. She was a law clerk to Thurgood Marshall, aiding him in the case Brown v. Board of Education. Motley was also the first African-American woman appointed to the federal judiciary, serving as a United States District Judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York.

CitePrintShare“Constance Baker Motley: My Inspiration to Be a Lawyer.” YouTube, 22 Mar. 2010, www.youtube.com/watch?v=F8X_Hu0eaQc&t=1s.

Fannie Lou Hamer, Testimony Before the Credentials Committee, Democratic National Convention (1964)Atlantic City, New Jersey - August 22, 1964Transcript...My husband came, and said the plantation owner was raising Cain because I had tried to register. Before he quit talking the plantation owner came and said, "Fannie Lou, do you know - did Pap tell you what I said?"

And I said, "Yes, sir."

He said, "Well I mean that." He said, "If you don't go down and withdraw your registration, you will have to leave." Said, "Then if you go down and withdraw," said, "you still might have to go because we are not ready for that in Mississippi."

And I addressed him and told him and said, "I didn't try to register for you. I tried to register for myself."

I had to leave that same night.

….All of this is on account of we want to register, to become first-class citizens. And if the Freedom Democratic Party is not seated now, I question America. Is this America, the land of the free and the home of the brave, where we have to sleep with our telephones off the hooks because our lives be threatened daily, because we want to live as decent human beings, in America?

Thank you.

[For a transcript of the complete text and audio: https://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/sayitplain/flhamer.html]

Fannie Lou Hamer was a field organizer for SNCC. In 1964, she ran for Congress with the Mississippi Freedom Democratic Party. The MFDP brought an alternate slate of delegates to the Democratic Party convention, arguing that the all-white Mississippi Democratic Party was mired in racism and did not represent the rights and needs of all. As described by American Public Media, the Mississippi “incumbent was a white man who had been elected to office twelve times. In an interview with the Nation, Hamer said, ‘I'm showing the people that a Negro can run for office.’”

CitePrintShareTestimony Before the Credentials Committee by Fannie Lou Hamer | Say It Plain, https://americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/sayitplain/flhamer.html.

Coretta Scott King, 10 Commandments on Vietnam (1968)Coretta Scott King, 10 Commandments on Vietnam (April 27, 1968) Central Park, New YorkTranscript….There is no reason why a nation as rich as ours should be blighted by poverty, disease, and illiteracy. It is plain that we don't care about our poor people except to exploit them as cheap labor and victimize them through excessive rents and consumer prices.

Our Congress passes laws which subsidize corporation farms, oil companies, airlines, and houses for suburbia. But when they turn their attention to the poor, they suddenly become concerned about balancing the budget and cut back on the funds for Head Start, Medicare, and mental health appropriations.

The most tragic of these cuts is the welfare section to the Social Security amendment, which freezes federal funds for millions of needy children, who are desperately poor but who do not receive public assistance. It forces mothers to leave their children and accept work or training, leaving their children to grow up in the streets as tomorrow's social problems. This law must be repealed, and I encourage you to join welfare mothers on May 12th, Mother's Day and call upon Congress to establish a guaranteed annual income, instead of these racist and archaic measures, these measures which dehumanize God's children and create more social problems than they solve.

We will be marching toward Washington soon. On Thursday, May 2nd we will return to Memphis to begin where my husband was slain and kick off his Poor People's campaign.

I would now like to address myself to the women. The woman power of this nation can be the power which makes us whole and heals the rotten community, now so shattered by war and poverty and racism. I have great faith in the power of women who will dedicate themselves whole-heartedly to the task of remaking our society.

I believe that the women of this nation and of the world are the best and last hope for a world of peace and brotherhood….

A musician and music educator, Coretta Scott King married Martin Luther King, Jr. in 1953. They had four children, and she traveled throughout the country and the world as an advocate for social justice with Dr. King.

This speech followed the assassination of Dr. King by just a few weeks. She used notes he had written for the speech, which she found in a jacket pocket of his after his death.

CitePrintShare“Coretta Scott King -- 10 Commandments on Vietnam.” American Rhetoric, 24 April 2022, https://www.americanrhetoric.com/speeches/corettascottkingvietnamcommandments.htm.

Interview with Ella Baker (1968)Although she was a leader and architect of many of the key elements of the Civil Rights Movement, Ella Baker is often overlooked in coverage of the era. She helped to lead and organize the NAACP, the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC), and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC). In this interview, she describes the role she played and the occasional tensions among leaders of the movement.

The Civil Rights Documentary Project Oral History/Interview with Ella Baker (1968)

A [PARTIAL] Transcript of a Recorded Interview with Miss Ella Baker, Staff-Member-Consultant with SCEF, Southern Conference Educational Fund. By John Britton, Interviewer, Washington, D.C. June 19, 1968

Britton: So, what you're saying, then, is that the genesis of the idea for SCLC [the Southern Christian Leadership Conference] started in the minds of the people in the North, not in Montgomery?

Baker: That's correct. You see, if you recall, after the [Montgomery Bus Boycott] there was almost sort of a complete let down. Nothing was happening. In fact, after I had become associated with the leadership from Montgomery, question was raised about why there was this not-knowing, why there was no organizational machinery for making use of the people who had been involved in the boycott?

I think, to some extent as it seems to have been my characteristic in raising certain kinds of questions, I irritated Dr. King in raising this question. I raised it at a meeting at which he was speaking. I think his rationale was something to the effect that after a big demonstrative type of action, there was a natural let-down and a need for people to sort of catch their breath, you see, which, of course, I didn't quite agree with. But, nevertheless, this was what took place.

So, I don't think that the leadership of Montgomery was prepared to capitalize, let's put it, on the projection that had come out of the Montgomery situation. Certainly, they had not reached the point of developing an organizational format for the expansion of it. So discussions emanated, to a large extent, from up this way.

CitePrintShareBritton, John. “Veterans of the Civil Rights Movement -- Ella Baker.” Civil Rights Movement Archive, https://www.crmvet.org/nars/baker68.htm.

Shirley Chisholm, Speech on the floor of the House of Representatives, “I Am for the Equal Rights Amendment” (1970)Shirley Chisholm was the first Black woman elected to Congress and the first Black person to run for President from one of the nation’s two major political parties, in 1972. She was an educator and civil rights activist, and she served for decades as a legislator and political leader.

Shirley Chisholm, Speech on the floor of the House of Representatives, “I Am for the Equal Rights Amendment.” (1970)

It is time we act to assure full equality of opportunity to those citizens who, although in a majority, suffer the restrictions that are commonly imposed on minorities, to women.

The argument that this amendment will not solve the problem of sex discrimination is not relevant. If the argument were used against a civil rights bill, as it has been used in the past, the prejudice that lies behind it would be embarrassing. Of course laws will not eliminate prejudice from the hearts of human beings. But that is no reason to allow prejudice to continue to be enshrined in our laws — to perpetuate injustice through inaction.

The amendment is necessary to clarify countless ambiguities and inconsistencies in our legal system. For instance, the Constitution guarantees due process of law, in the 5th and 14th amendments. But the applicability of due process of sex distinctions is not clear. Women are excluded from some State colleges and universities. In some States, restrictions are placed on a married woman who engages in an independent business. Women may not be chosen for some juries. Women even receive heavier criminal penalties than men who commit the same crime.

…The time is clearly now to put this House on record for the fullest expression of that equality of opportunity which our founding fathers professed. They professed it, but they did not assure it to their daughters, as they tried to do for their sons.

The Constitution they wrote was designed to protect the rights of white, male citizens. As there were no black Founding Fathers, there were no founding mothers — a great pity, on both counts. It is not too late to complete the work they left undone. Today, here, we should start to do so.

CitePrintShareO'Halloran, Thomas J. “(1970) Shirley Chisholm, “I Am For the Equal Rights Amendment.” Blackpast, 24 July 2008, https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/1970-shirley-chisholm-i-am-equal-rights-amendment/.

Angela Y. Davis, "An Open Letter to Black High School students” (1971)TranscriptDear Sisters and Brothers,

At least a decade separates me and others of my age from you, Black men and women in America’s high schools. But this difference is unimportant compared to the strong ties that unite us in a common struggle for the freedom of our people. Our responsibility towards you runs deep. In the course of fighting to overthrow the conditions which have locked our people in an iron cycle of deprivation, we have accumulated a multitude of experiences, experiences which must become your experiences – the victories as well as the defeats, the truths as well as the errors. We feel accountable to you in yet another way. You have grown to maturity in the heat of battle, you are the living reflections of new realities, new values which categorically reject the subservient role Black people have been compelled to play for centuries. Your aggressiveness and boldness must become our aggressiveness and boldness….

Angela Davis, scholar and member of the Black Panthers, wrote this letter while incarcerated in Marin County, California in 1971. Davis had been captured and arrested following an armed attack at the facility led by 17-year-old Jonathan Jackson, who was fighting for the release of his brother and other prisoners known as the “Soledad Brothers.” As described by journalist Antonio Mejias-Rentas, “Witnesses before a county grand jury testified that several of the weapons used in the courthouse takeover had been purchased by Davis, including a sawed-off shotgun that authorities said was used to kill Judge Haley. Although Davis had not been present, the grand jury returned an indictment charging her with kidnapping, murder and conspiracy. Davis never denied owning the weapons, but said she was not involved and had no knowledge of her weapons being used in the courthouse assault.”

CitePrintShareDavis, Angela. “An Open Letter to Black High School Students.” Harvard Mirador Viewer, 1971, iiif.lib.harvard.edu/manifests/view/drs:491078034$1i.

Mejías, Antonio. How Angela Davis Ended Up on the FBI Most Wanted List, 25 January 2023, https://www.history.com/news/angela-davis-fbi-most-wanted-list.

Condoleezza Rice, Speech to National Council of Negro Women (2001)A scholar of international affairs, Condoleezza Rice joined the administration of President George H.W. Bush as the Director for Soviet and Eastern European Affairs in the National Security Council. Later, after serving as the Provost of Stanford University, she became the first woman to direct the NSC, under then President George W. Bush. Her tenure included the attacks on 9/11 and the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, and in 2005 she became the first Black woman to serve as Secretary of State.

Condoleezza Rice, Speech to National Council of Negro Women, December 8, 2001 - Washington, D.C.

I could not be more honored than to receive the Bethune Award because I feel a great kinship with Mary McLeod Bethune and I think we all do. …It's extraordinary that a young, black woman from South Carolina could found a college and be its president for almost four decades.

…I also feel a great kinship to Dr. Bethune and to this organization because we share a passion for education. There is no more important element for the United States of America than the promise of education. I'm a living example of what education can mean, because it goes back a long way in my family. I very often tell people that I should have been able to accomplish what I accomplished because I had grandparents and parents who understood the value of education.

Maybe some of you've heard me tell the story of Granddaddy Rice, a poor sharecropper's son in Ewtah – that's E-W-T-A-H - Alabama, who, somehow, in about 1919 decided he was going to get book learning. And so he asked people who came through how a colored man could get to college. And they said to him, "Well you see there's this college not too far away from here called Stillman College, and if you could get there, they take colored men into college." And so he saved up his cotton and he went off to Tuscaloosa, Alabama to go to college. He made it through his first year having paid for it with his cotton, but the second year he didn't have any more cotton, and they came and they asked him for tuition. And he said, "Well you see the problem is, I don't have any money." And they said, "Well, you'll have to leave." So he thought rather quickly and he said, "Well how are those boys going to college?" And they said, "Well, you see, they have what's called a scholarship and if you wanted to be a Presbyterian minister then you could have a scholarship too." And Granddaddy Rice said, "You know, that's exactly what I had in mind. And my family has been Presbyterian and it has been college-educated ever since.

My grandfather understood something, and so did my grandmother and my mother's parents, and that is that higher education, if you can attain it, is transforming. You may come from a poor family, you may come from a rural family, you may be first-generation college-educated, but once you are college-educated, the most important thing about you, in many ways, is that you're a college graduate and you are transformed. And I have to tell you that if I have a concern at all today in America, it is that we have got to find a way to pass on that promise to children, no matter what their circumstances, because it's just got to be the case in America that it does not matter where you came from, it only matters where you're going.

CitePrintShareMedia, American Public. “American Radioworks - Say It Plain, Say It Loud.” APM Reports - Investigations and Documentaries from American Public Media, americanradioworks.publicradio.org/features/blackspeech/crice.html.

Education for American Democracy

In this lesson, students will learn about the initial phase of the grape workers’ strike that occurred in California’s San Joaquin Valley from 1965 to 1966 by exploring images related to the farmworkers' movement, and by watching a video that explains the events that occurred in the first year of the strike to analyze the strategies used during this period of the farmworkers’ movement and reflect on the impact these strategies had.

The Roadmap

Facing History and Ourselves

Lewis Hine shot hundreds of photographs that exposed the working conditions facing thousands of child laborers in the first two decades of the twentieth century. His powerful images shed light on a world largely hidden from most middle-class Americans and influenced public debate about child labor laws. This lesson asks students to think critically about Hine’s photographs and their usefulness as evidence of the past.

The Roadmap

Stanford History Education Group

In this lesson plan, students will read, view, and discuss child labor before reforms were made in our country.

The Roadmap

Alabama Department of Archives and History

On the occasion of the launch of the Mandela Children’s Fund, Nelson Mandela said, “There can be no keener revelation of a society's soul than the way in which it treats its children.” Children have often been caught up and played a role in the ideological and political movements that have taken place throughout U.S. History. What can we learn about these political and ideological movements through the lens of children and their experiences? When we frame our study of the past through the experiences of children and adolescents, we create pathways for connection and curiosity for our students. There are many ways you might use these sources in your curriculum. Use these sources individually, as you cover a particular era, or collectively, as students examine change and continuity in the experiences of children and teens over time. Sources are indexed below by theme and era and each source includes a brief description as well as guiding questions for use in the classroom.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by SubthemeEducation and its Impact on Children and Teens (12)Children and Public Activism (7)

- Primary Resources by Era/DateColonial Era (3)Nineteenth Century (3)1930s - 1940s (3)1940s, 50s, and 60s (9)Early Twentieth Century and WWI (6)

- All 24 Primary ResourcesContract for the Indenture of Elizabeth Fortune, Aged 9, 1723Contract for the Indenture of Elizabeth Fortune, Aged 9, 1723Transcript

John Fortune and Maria his wife have by these presents put, placed, and bound their daughter Elizabeth Fortune aged nine years the first day of March last past as an apprentice with the Said Elizabeth Sharpas

as an apprentice with her, the said Elizabeth Sharpas, to dwell from the day of the date of these presents for and during the term of Nine Years…The Said Elizabeth Fortune unto according to her power, wit, and ability and honestly and obediently in all things shall behave herself towards her said Mistress and all hers and shall not contract matrimony during the said Term.

Elizabeth Sharpas for her part promises, Covenants, agrees that she the said Elizabeth Sharpas apprenticed Elizabeth Fortune in the art and skill of housewifery.

This document provides a glimpse into the experiences of colonial children who spent much of their childhood working for families that were not their own. This indenture arraignment also highlights the kinds of skills and education that were valued for girls. Namely, Elizabeth Fortune is said to receive training in the “art of housewifery” in exchange for her service.

CitePrintShare“Indenture of Elizabeth Fortune, September 10, 1723,” Women & the American Story, https://wams.nyhistory.org/settler-colonialism-and-revolution/settler-colonialism/children-at-work/#. Accessed 1 April 2022.

Needlework by Sarah Anne Janeway, 1783 - Training for domestic workSewn Sampler made by 11-year-old Sarah Anne Janeway, 1783Young colonial girls raised in wealthy households were trained in the skills of a housewife early on. Samplers like this one displayed a girl's aptitude for needlework and could be hung as a piece of art in a family household.

CitePrintShare“Symbols of Accomplishment - Women & the American Story.” Women & the American Story, https://wams.nyhistory.org/settler-colonialism-and-revolution/settler-colonialism/symbols-of-accomplishment/#. Accessed 1 April 2022.

A New England Primer, 1803 - The role of religion in educationIn colonial New England, a primer like this one may have been in use as early as 1690. Children first learned their ABCs and basic literacy through primers. Since the Bible was seen as the primary means through which a child would attain literacy, these primers would often incorporate religious themes and morals.

CitePrintShareWestminster Assembly. “The New-England primer,” Boston: Printed for and sold by A. Ellison, in Seven-Star Lane, 1773. Pdf. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/22023945/>. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Perry Lewis (b. 1850), formerly enslaved, recounts his childhood in Baltimore, M.D. - Enslaved children and lack of access to educationPerry Lewis (b. 1850), formerly enslaved, recounts his childhood in Baltimore, M.D.TranscriptAs you know the mother was the owner of the children that she brought into the world Mother being a slave made me a slave. She cooked and worked on the farm, ate whatever was in the farmhouse and did her share of work to keep and maintain the Tolsons.

They being poor, not having a large place or a number of slaves to increase their wealth, made them little above the free colored people and with no knowledge, they could not teach me or anyone else to read…

In my childhood days, I played marbles, this was the only game I remember playing. As I was on a small farm, we did not come in contact much with other children and heard no childrens’ songs. I therefore do not recall the songs we sang.

Records from the Federal Writers Project are of immense importance in documenting and preserving the experiences of those who survived enslavement. ; Lewis’ account includes reference to the concept of hypodescent, which allowed intergenerational, chattel slavery to persist in the U.S. Lewis also makes note of his lack of access to education and some memories of his childhood.

1- Miletich, Patricia. “Religion and Literacy in Colonial New England | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History |, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/lesson-plan/religion-and-literacy-colonial-new-england. Accessed 2 April 2022.

- For more on the Federal Writer’s Project see Smith, Clint. “The Value of the Federal Writers' Project Slave Narratives.” The Atlantic, 9 February 2021, https://www.theatlantic.com/magazine/archive/2021/03/federal-writers-project/617790/. Accessed 19 April 2022.

CitePrintShareFederal Writers' Project: Slave Narrative Project, Vol. 8, Maryland, Brooks-Williams. 1936. Manuscript/Mixed Material. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/mesn080/>. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Before and After Photos of Children enrolled in Carlilse Residential Indian School, 1890s - Residential School SystemOne of the “before-and-after-education” photographs of Sioux boys taken before arriving at boarding school in the 1890s.At Carlisle Indian School in Pennsylvania, and other residential schools like it, Native American children and teens were required to give up their tribal traditions and culture. Carlisle opened in 1879 as the first government-run residential school, aimed at forcing Indigenous youth to assimilate to White culture. These before and after photos were taken as a way to demonstrate the efforts at assimilation.

1- “Richard Henry Pratt Carlisle Indian School.” Carlisle Indian School Project, https://carlisleindianschoolproject.com/past/. Accessed 2 April 2022.

CitePrintShareImage 1: "Sioux boys as they arrived at Carlisle," Digital Public Library of America, http://dp.la/item/d7ca78d98ae563bfefd20c2620613c8b. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Image 2: "Sioux boys 3 years after arriving at Carlisle," Digital Public Library of America, http://dp.la/item/f7b6ae7adfd4a9c9ecbceaf3af5fa8b5. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Sample Program For One Week - Residential School SystemSample daily program for one week at an Indian school, 1914Life for a student at the Carlisle Indian School was highly regimented and militaristic, signaling the government’s influence on the school’s mission and identity. This source, paired with the images above, offers a glimpse into the daily experience of those enrolled in this program as well as information about the aims of the federal government in establishing institutions such as Carlisle.

CitePrintShare“Cover letter, January 23, 1914, with attached sample daily program for one week at an Indian school”; 1/1914; Records of the Bureau of Indian Affairs, Record Group 75. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/cover-letter-january-23-1914-with-attached-sample-daily-program-for-one-week-at-an-indian-school. Accessed March 24, 2022.

Mary Ann Yahiro recites the Pledge of Allegiance at Raphael Weill School in San Francisco before being sent to Topaz internment camp in Utah, April 1942 - Japanese IntenmentMary Ann Yahiro, center, recites the Pledge of Allegiance at Raphael Weill School in San Francisco in April 1942 before being sent to Topaz internment camp in Utah.This photograph shows a group of children in the Weil Public School reciting the pledge of allegiance to the U.S. flag. The young girl in the front row center is Helen Mihara. A few months before this image was taken, Helen’s father, a San Francisco businessman, was arrested and detained in a Department of Justice camp for “enemy aliens.” Soon after this image was taken, Helen and her mother were placed in Tule Lake Relocation Center. Her mother later died in detention.

1- “San Francisco, Calif., April 1942 - Children of the Weill public school, from the so-called international settlement, shown in a flag pledge ceremony. Some of them are evacuees of Japanese ancestry who will be housed in War relocation authority centers for.” Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2001705926/. Accessed 5 April 2022.

CitePrintShareLange, Dorothea, photographer. San Francisco, Calif., April- Children of the Weill public school, from the so-called international settlement, shown in a flag pledge ceremony. Some of them are evacuees of Japanese ancestry who will be housed in War relocation authority centers for the duration. [April] Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2001705926/>. Accessed April 10, 2022.

TIME Magazine Feature on the American “teen-ager," 1944 - American Teenage Girls“The Invention of the American “teen-ager,” 1944Although it is not a certainty, some historians believe that the concept of the American “teenager” originated sometime in the 1940s. A liminal age, the teenager was neither child nor adult. This 1944 TIME Magazine article detailed the “life of the American Teenager” by photojournalist Nina Leen. The full article offers a glimpse into the perception of teens but also offers opportunities for students to consider the rise of the middle class, social status, and race in the middle of the twentieth century.

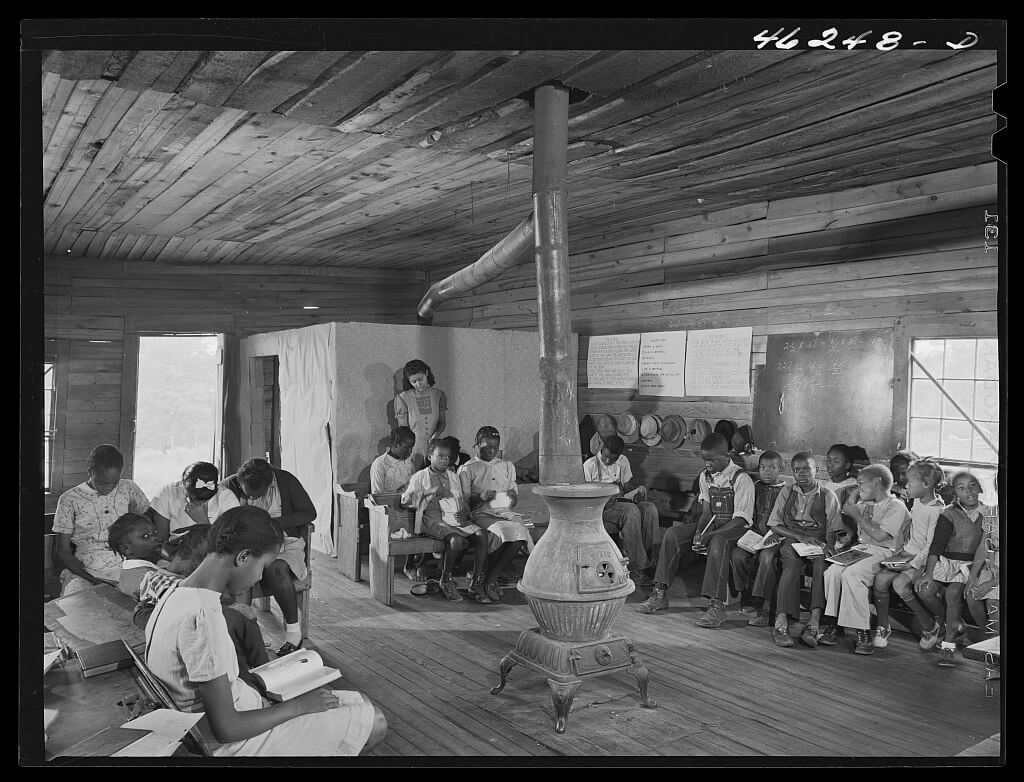

Separate but Unequal: Two classrooms before Brown v. Board of Education, Georgia, 1941 - School SegregationSchool segregation was among the most central concerns of the Civil Rights Movement since the 1930s. Activists for school integration argued that separate was not equal and every child, regardless of race, was entitled to education in a safe learning environment. These two images depict daily life in segregated classrooms in the same year, 1941. Brown v. Board of Education would not be passed for more than a decade.

1- “Recovery Programs.” Recovery Programs | DPLA, https://dp.la/exhibitions/new-deal/recovery-programs/farm-security-administration?item=409. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareImage 1: Delano, J., photographer. (1941) Veazy, Greene County, Georgia. The one-teacher Negro school in Veazy, south of Greensboro. United States Greene County Georgia Veazy, 1941. Oct. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017796657/. Accessed April 10, 2022.

Image 2: Delano, J., photographer. (1941) Siloam, Greene County, Georgia. Classroom in the school. United States Greene County Siloam Georgia, 1941. Oct. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017796554/. Accessed April 10, 2022.

Telegram from Parents of the Little Rock Nine to President Dwight D. Eisenhower, 1957-58 - School IntegrationTelegram from Parents of the Little Rock Nine to President Dwight D. EisenhowerWritten three years after the passage of Brown v. Board of Education, this telegram to President Eisenhower details the feelings of parents of the Little Rock Nine, who were a part of the busing program to integrate the Little Rock school system. The Little Rock Nine were the first African American students to enter Little Rock’s Central High School in Arkansas. The parents note that because of the supreme court ruling their “faith in democracy” had been renewed.

1- “The Little Rock Nine.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/little-rock-nine. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareTelegram from Parents of the Little Rock Nine to President Dwight D. Eisenhower; 10/1957; OF 142-A-5 Negro Matters - Colored Question (5), 1957 - 1958; Official Files, 1953 - 1961; Collection DDE-WHCF: White House Central Files (Eisenhower Administration), 1953 - 1961; Dwight D. Eisenhower Library, Abilene, KS. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/telegram-parents-little-rock-nine-to-president-eisenhower. Accessed April 1, 2022.

African American children on their way to PS204, 82nd Street, and 15th Avenue, pass mothers protesting the busing of children to achieve integration, 1965 - School IntegrationAfrican American children on their way to PS204, 82nd Street, and 15th Avenue, pass mothers protesting the busing of children to achieve integrationEven after the passage of Brown v. Board of Education, school integration was protested. This image shows African American children entering their new school while white mothers protest school integration

CitePrintShareDemarsico, Dick, photographer. African American children on way to PS204, 82nd Street and 15th Avenue, pass mothers protesting the busing of children to achieve integration (1965). Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2004670162/>. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Audio Recording: Conversation with 11 and 12-year-old black females, Meadville, Mississippi, 1973 - Daily life for two pre-teens in DetriotThis conversation was originally recorded as part of an effort to archive regional dialects by the Library of Congress. It also provides a glimpse into the daily lives of pre-teen girls, including racial discrimination they faced in their school community.

Audio Recording: Conversation with 11 and 12-year-old black females, Meadville, Mississippi

CitePrintShareUnidentified, and Walt Wolfram. Conversation with 11 and 12-year-old black females, Meadville, Mississippi. to 1973, 1972. Audio. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/afccal000213/>. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Mother Jones and Children Laborers go on Strike, 1903Mother Jones and Children Laborers go on Strike, 1903In July of 1903, Mother Jones led a march from Philadelphia to the home of President Rosevelt to protest the unsafe labor conditions of children working in mills. The story of Mother Jones and the children who accompanied her on her march showcases not only youth activism but also women in the labor movement at the turn of the century.

1- Lauren Cooper. “July 7, 1903: March of the Mill Children.” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/mother-jones-march-mill-children/. Accessed 3 April 2022.

CitePrintShare"Mother" Jones and her army of striking textile workers starting out for their descent on New York The textile workers of Philadelphia say they intend to show the people of the country their condition by marching through all the important cities”; 1903; Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/pictures/item/2015649893/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Child Labor Standards, 1916Child Labor StandardsThis ad was created after the passage of the Keating-Own Child Labor Act of 1916. This act limited the working hours of children and placed an age requirement of the age of 16 for any working child. It also forbade the interstate sale of goods produced in factories that employed child labor.

CitePrintShare"Child Labor Standards"; ca. 1941-1945; Records of the Office of War Information, Record Group 208. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/child-labor-standards. April 1, 2022.

Girl Scouts and the War EffortGirl Scout Troup Plants a Victory Garden, 1917Girl Scout Pledge Card to Save for a Soldier, 1914After the US declared war in 1917, children were encouraged to support the war efforts. The Girl Scouts of America provided an opportunity for girls to become involved in volunteer work for the war effort. Organizations like the Girls Scouts and 4H typically trained girls for domestic work. Skills like sewing and first-aid were put to use in new ways for members of the Girl Scouts and 4H during WWI. Here, scouts planted a Victory Garden. Victory gardens, or liberty gardens, first appeared during WWI. The federal government encouraged citizens to plant vegetable gardens to mitigate any food shortages that resulted from the war.

1- Lauren Cooper. “July 7, 1903: March of the Mill Children.” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/mother-jones-march-mill-children/. Accessed 3 April 2022.

- Spring, Kelly A. “Girls' Volunteer Groups during World War I.” National Women's History Museum, https://www.womenshistory.org/resources/general/girls-volunteer-groups-during-world-war-i. Accessed 3 April 2022.

CitePrintShareImage 1: Harris & Ewing, photographer. NATIONAL EMERGENCY WAR GARDENS COM. GIRL SCOUTS GARDENING AT D.A.R. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2016867777/>. Accessed April 2, 2022.

Image 2: “Girl Scout Pledge Card "To Save for a Solder”. 1914. Girl Scout Archive Management Center. https://archives.girlscouts.org/Detail/objects/64958. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Boy Scouts as Bond Workers, 1917Boy Scouts as Bond Workers, 1917Boyscouts, like Girl Scouts, volunteered in the war effort during both WWI and II. Here, scouts who were too young to go to combat sell war bonds.

CitePrintShareBain News Service, Publisher. Boy Scouts as bond workers. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2014704734/>. Accessed April 10, 2022.

12-Year-Old Girl at the March on Washington, 196312-Year-Old Girl at the March on WashingtonOn August 28, 1963, thousands took part in the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom. The March was instigated by a continuing lack of jobs for African Americans and the persistence of segregation. The march was influential in pressuring President John F. Kennedy to draft a strong civil rights bill. This photo depicts Edith Lee-Payne on her twelfth birthday. Edith attended the March with her mother.

1- “March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom | The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute.” The Martin Luther King, Jr., Research and Education Institute |, https://kinginstitute.stanford.edu/encyclopedia/march-washington-jobs-and-freedom. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintSharePhotograph 306-SSM-4C-61-32; Young Woman at the Civil Rights March on Washington, D.C. with a Banner; 8/28/1963; Miscellaneous Subjects, Staff and Stringer Photographs, 1961 - 1974; Records of the U.S. Information Agency, Record Group 306; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/girl-march-on-washington-banner. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Protests in support of the 26th Amendment, 1969Protests in support of the 26th AmendmentThe 26th Amendment to the Constitution allowed for those 18 years old or older to vote in elections. Support for decreasing the voting age from 21 to 18 increased during World War II, as young men were conscripted to fight in the war as young as 18 but could not yet vote. This image depicts youth protestors in support of the 26th amendment.

1- “The 26th Amendment | Richard Nixon Museum and Library.” Nixon Presidential Library, 17 June 2021, https://www.nixonlibrary.gov/news/26th-amendment. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShare“Demonstration for reduction in voting age, Seattle, 1969”; Seattle Post-Intelligencer Collection, Museum of History & Industry, Seattle; https://digitalcollections.lib.washington.edu/digital/collection/imlsmohai/id/1715/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Little Spinner in Globe Cotton Mill, Augusta, Ga., 1909Little Spinner in Globe Cotton Mill, Augusta, Ga., 1909Images of children laborers at the turn of the century reveal the experiences of children who spent most of their days working in the oftentimes harsh and unsafe conditions of urban factories. After the Civil War, as industry grew in urban areas, children often worked in factories, in markets, and on the streets as vendors.

Children Working in a Textile Mill in Georgia, 1909Children Working in a Textile Mill in GeorgiaLike the image above, this source shows a young child operating machinery that he is not even tall enough to reach. Images like these and the one above were captured by activists for child labor laws. The Child labor standards act would be passed in 1916

1- Schuman, Michael. “History of child labor in the United States—part 1: little children working: Monthly Labor Review: US Bureau of Labor Statistics.” Bureau of Labor Statistics, https://www.bls.gov/opub/mlr/2017/article/history-of-child-labor-in-the-united-states-part-1.htm. Accessed 19 April 2022.

CitePrintSharePhotograph 102-LH-488; Bibb Mill No. 1, Macon, Ga.; 1/19/1909; Bibb Mill No. 1, Macon, Ga. Many youngsters here. Some boys and girls were so small they had to climb up onto the spinning frame to mend broken threads and to put back the empty bobbins.,; Records of the Children's Bureau, Record Group 102; National Archives at College Park, College Park, MD. [Online Version, https://www.docsteach.org/documents/document/bibb-mill. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Spread from Look magazine on sharecropping children, 1937Page from Look magazine, 1937 on sharecropping childrenThis magazine spread on sharecropping children was published the same year that President Rosevelt established the Farm Security Administration. The FSA was a New Deal agency that provided assistance and relief to agricultural workers impacted by drought and the Great Depression.

1- “Gardening for the Common Good.” Smithsonian Libraries, https://library.si.edu/exhibition/cultivating-americas-gardens/gardening-for-the-common-good. Accessed 19 April 2022.

CitePrintSharePages 18 and 19 of March Look magazine. Photograph. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2017760274/>. April Accessed April 10, 2022.

Boys playing marbles, Farm Security Administration labor camp, Robstown, Texas, 1944Boys playing marbles, Farm Security Administration labor camp, Robstown, Texas, 1944During the Great Depression, The Farm Security Administration attempted to aid workers and farmers by setting up housing camps, providing loans and training to workers, among other forms of assistance. This source shows a group of children playing marbles in one of the FSA labor camps in Texas, offering a glimpse into daily life and play for children living through the Great Depression.

CitePrintShareRothstein, A., photographer. (1942) Boys playing marbles, FSA ... labor camp, Robstown, Texas. United States Robstown Texas, 1942. Jan. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2017877649/. Accessed April 10, 2022.

School Closures during Little Rock Nine: Girls learn from Home, 1958 - School IntegrationSchool Closures during Little Rock 9: three pajama-clad white girls being educated via television during the period that the Little Rock schools were closed to avoid integration.In September 1958, Governor Faubus of Arkansas closed all Little Rock public high schools as a result of unrest due to integration. Known as the “Lost Year,” both teachers and students were blocked from their school buildings. This image shows three girls learning “remotely” during that time and offers a glimpse of the efforts to maintain continuity of education in the midst of upheaval.

1- “The Little Rock Nine.” National Museum of African American History and Culture, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/little-rock-nine. Accessed 4 April 2022.

- “Sept. 12, 1958: Little Rock Public Schools Closed.” Zinn Education Project, https://www.zinnedproject.org/news/tdih/little-rock-schools-closed/. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareO'Halloran, T. J., photographer. (1958) Little Rock, Ark. Attempts to reopen schools / TOH. Arkansas Little Rock, 1958. Sept. [Photograph] Retrieved from the Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2003654390/. Accessed April 1, 2022.

Letter from Linda Kelly, Sherry Bane, and Mickie Mattson to President Dwight D. Eisenhower Regarding Elvis Presley, 1953-1961Letter from Linda Kelly, Sherry Bane, and Mickie Mattson to President Dwight D. Eisenhower Regarding Elvis Presley, 1953-1961Celebrities were no exception to the draft during the Vietnam War. Elvis Presley joined the army in 1958 and, in this letter, three girls from Nevada ask President Eisenhower not to shave off his sideburns. This source offers a window into the lives of American teens as well as an example of the role teens played in the evolution and development of American pop culture.

1- Cosgrove, Ben. “The Invention of Teenagers: LIFE and the Triumph of Youth Culture.” Time.com, TIME, 28 September 2013, https://time.com/3639041/the-invention-of-teenagers-life-and-the-triumph-of-youth-culture/. Accessed 4 April 2022.

CitePrintShareBane, Sherry Author, Linda Author Kelly, and Mickie Author Mattson. Letter from Linda Kelly, Sherry Bane, and Mickie Mattson to President Dwight D. Eisenhower Regarding Elvis Presley. [Place of Publication Not Identified: Publisher Not Identified, 1958] Image. Retrieved from the Library of Congress, <www.loc.gov/item/2021667581/> Accessed April 4, 2022.

- Additional Resources

- Teacher's Guides and Analysis Tool | Getting Started with Primary Sources | Teachers | Programs | Library of Congress

- Document Analysis Overview | National Archives

- Activity Tools | DocsTeach

- Primary Source Activity Guide | EAD Team

Education for American Democracy

In this lesson, students explore ideas about citizenship, power, and responsibility by listening to and discussing a podcast featuring an interview with Eric Liu, the founder and CEO of Citizen University, to deepen their understanding of citizen power.

The Roadmap

Facing History and Ourselves

This lesson helps students explore the question, "What does it mean to be a good citizen, and how do citizens learn to use their power to make change?" using the work of civic entrepreneur Eric Liu.

The Roadmap

Facing History and Ourselves

As a foundation for studying the rights and responsibilities of citizens, students will learn what it means to be a citizen and how people become US citizens. They will also examine how the right of US citizenship has changed over time.

The Roadmap

iCivics, Inc.

In this lesson, students will think about the definition of democracy and then consider how it might relate to the communities and culture in which they live and participate.

The Roadmap

Facing History and Ourselves

This lesson plan guides students through a "jigsaw" learning activity, in which they read about four notable examples of investigative journalism, then share their newfound knowledge with their classmates. The resource includes informational handouts and two graphic organizers for students to fill out, with the overarching goal of teaching the importance of a free press to democracy.

The Roadmap

The News Literacy Project

In this lesson, students will examine the final speech delivered by Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and deepen their understanding of the text by illustrating and summarizing Dr. King’s main ideas and imagery, and they will then use excerpts to create a class poem and later reflect on how they might “choose to participate” in creating of a more just community, nation, or world.

The Roadmap

Facing History and Ourselves

Download the Roadmap and Report

Download the Educating for American Democracy Roadmap and Report Documents

Get the Roadmap and Report to unlock the work of over 300 leading scholars, educators, practitioners, and others who spent thousands of hours preparing this robust framework and guiding principles. The time is now to prioritize history and civics.

Your contact information will not be shared, and only used to send additional updates and materials from Educating for American Democracy, from which you can unsubscribe.

We the People

This theme explores the idea of “the people” as a political concept–not just a group of people who share a landscape but a group of people who share political ideals and institutions.

Institutional & Social Transformation

This theme explores how social arrangements and conflicts have combined with political institutions to shape American life from the earliest colonial period to the present, investigates which moments of change have most defined the country, and builds understanding of how American political institutions and society changes.

Contemporary Debates & Possibilities

This theme explores the contemporary terrain of civic participation and civic agency, investigating how historical narratives shape current political arguments, how values and information shape policy arguments, and how the American people continues to renew or remake itself in pursuit of fulfillment of the promise of constitutional democracy.

Civic Participation

This theme explores the relationship between self-government and civic participation, drawing on the discipline of history to explore how citizens’ active engagement has mattered for American society and on the discipline of civics to explore the principles, values, habits, and skills that support productive engagement in a healthy, resilient constitutional democracy. This theme focuses attention on the overarching goal of engaging young people as civic participants and preparing them to assume that role successfully.

Our Changing landscapes

This theme begins from the recognition that American civic experience is tied to a particular place, and explores the history of how the United States has come to develop the physical and geographical shape it has, the complex experiences of harm and benefit which that history has delivered to different portions of the American population, and the civics questions of how political communities form in the first place, become connected to specific places, and develop membership rules. The theme also takes up the question of our contemporary responsibility to the natural world.

A New Government & Constitution

This theme explores the institutional history of the United States as well as the theoretical underpinnings of constitutional design.

A People in the World

This theme explores the place of the U.S. and the American people in a global context, investigating key historical events in international affairs,and building understanding of the principles, values, and laws at stake in debates about America’s role in the world.

The Seven Themes

The Seven Themes provide the organizational framework for the Roadmap. They map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. Importantly, they are neither standards nor curriculum, but rather a starting point for the design of standards, curricula, resources, and lessons.

Driving questions provide a glimpse into the types of inquiries that teachers can write and develop in support of in-depth civic learning. Think of them as a starting point in your curricular design.

Learn more about inquiry-based learning in the Pedagogy Companion.

Sample guiding questions are designed to foster classroom discussion, and can be starting points for one or multiple lessons. It is important to note that the sample guiding questions provided in the Roadmap are NOT an exhaustive list of questions. There are many other great topics and questions that can be explored.

Learn more about inquiry-based learning in the Pedagogy Companion.

The Seven Themes

The Seven Themes provide the organizational framework for the Roadmap. They map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions that students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. Importantly, they are neither standards nor curriculum, but rather a starting point for the design of standards, curricula, resources, and lessons.

The Five Design Challenges

America’s constitutional politics are rife with tensions and complexities. Our Design Challenges, which are arranged alongside our Themes, identify and clarify the most significant tensions that writers of standards, curricula, texts, lessons, and assessments will grapple with. In proactively recognizing and acknowledging these challenges, educators will help students better understand the complicated issues that arise in American history and civics.

Motivating Agency, Sustaining the Republic

- How can we help students understand the full context for their roles as civic participants without creating paralysis or a sense of the insignificance of their own agency in relation to the magnitude of our society, the globe, and shared challenges?

- How can we help students become engaged citizens who also sustain civil disagreement, civic friendship, and thus American constitutional democracy?

- How can we help students pursue civic action that is authentic, responsible, and informed?

America’s Plural Yet Shared Story

- How can we integrate the perspectives of Americans from all different backgrounds when narrating a history of the U.S. and explicating the content of the philosophical foundations of American constitutional democracy?

- How can we do so consistently across all historical periods and conceptual content?

- How can this more plural and more complete story of our history and foundations also be a common story, the shared inheritance of all Americans?

Simultaneously Celebrating & Critiquing Compromise

- How do we simultaneously teach the value and the danger of compromise for a free, diverse, and self-governing people?

- How do we help students make sense of the paradox that Americans continuously disagree about the ideal shape of self-government but also agree to preserve shared institutions?

Civic Honesty, Reflective Patriotism

- How can we offer an account of U.S. constitutional democracy that is simultaneously honest about the wrongs of the past without falling into cynicism, and appreciative of the founding of the United States without tipping into adulation?

Balancing the Concrete & the Abstract

- How can we support instructors in helping students move between concrete, narrative, and chronological learning and thematic and abstract or conceptual learning?

Each theme is supported by key concepts that map out the knowledge, skills, and dispositions students should be able to explore in order to be engaged in informed, authentic, and healthy civic participation. They are vertically spiraled and developed to apply to K—5 and 6—12. Importantly, they are not standards, but rather offer a vision for the integration of history and civics throughout grades K—12.

Helping Students Participate

- How can I learn to understand my role as a citizen even if I’m not old enough to take part in government? How can I get excited to solve challenges that seem too big to fix?

- How can I learn how to work together with people whose opinions are different from my own?

- How can I be inspired to want to take civic actions on my own?

America’s Shared Story

- How can I learn about the role of my culture and other cultures in American history?

- How can I see that America’s story is shared by all?

Thinking About Compromise

- How can teachers teach the good and bad sides of compromise?

- How can I make sense of Americans who believe in one government but disagree about what it should do?

Honest Patriotism

- How can I learn an honest story about America that admits failure and celebrates praise?

Balancing Time & Theme

- How can teachers help me connect historical events over time and themes?

The Six Pedagogical Principles

EAD teacher draws on six pedagogical principles that are connected sequentially.

Six Core Pedagogical Principles are part of our Pedagogy Companion. The Pedagogical Principles are designed to focus educators’ effort on techniques that best support the learning and development of student agency required of history and civic education.