The curated resources linked below are an initial sample of the resources coming from a collaborative and rigorous review process with the EAD Content Curation Task Force.

Reset All

Reset All

This lesson plan focuses on two prominent Supreme Court cases on the internment of Japanese-Americans during WWII, and it asks students to consider the executive branch's authority regarding individual liberties during times of war.

The Roadmap

Annenberg Classroom

This learning resource uses geospatial technology to help students understand the many components of the Pearl Harbor Attacks. Guided by inquiry, students will use the ArcGIS map to investigate the how the Japanese executed this attack and how the positioning of the U.S. in Oahu made the perfect target.

The Roadmap

Esri

The phrase “a house divided” comes from Abraham Lincoln’s speech to the Illinois Republican State Convention in 1858, when he describes a nation so badly torn between those that permitted slavery and those that prohibited it that it was on the brink of war. While the issue of slavery is understood to be central to the start of the Civil War, this set of resources is intended to introduce students to more details of the growing tension in the nation. Resources include information and images about expanding territory and the addition of new states to the union; voices of the abolitionist movement; political tension and acts of violence. It does not provide comprehensive coverage of these decades, but it helps to highlight that the growing tension was both multifaceted and happening across the entire nation.

The resources in this spotlight kit are intended for classroom use, and are shared here under a CC-BY-SA license. Teachers, please review the copyright and fair use guidelines.

The Roadmap

- Primary Resources by Decade1830s (4)1840s (3)1850s (9)

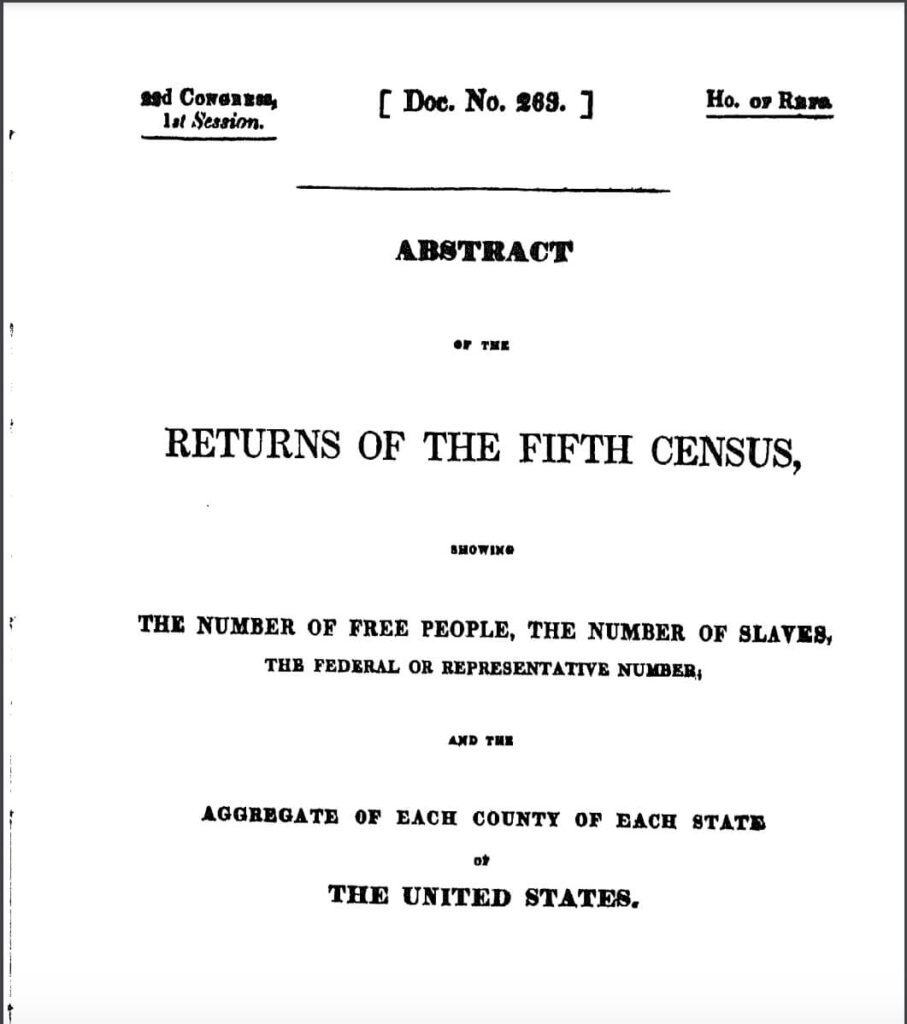

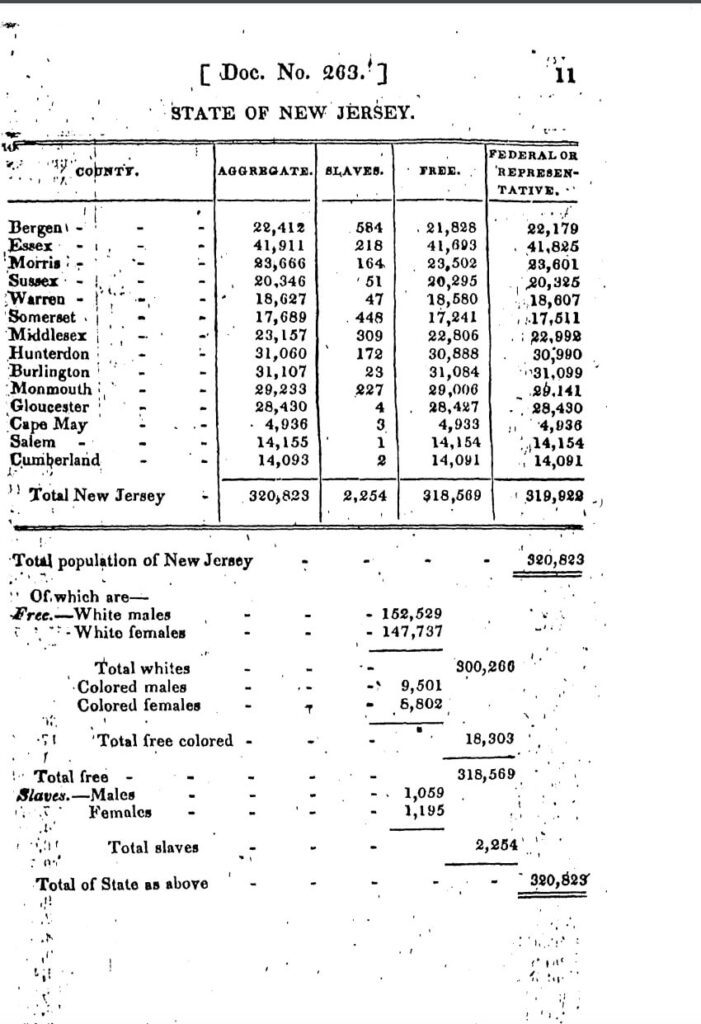

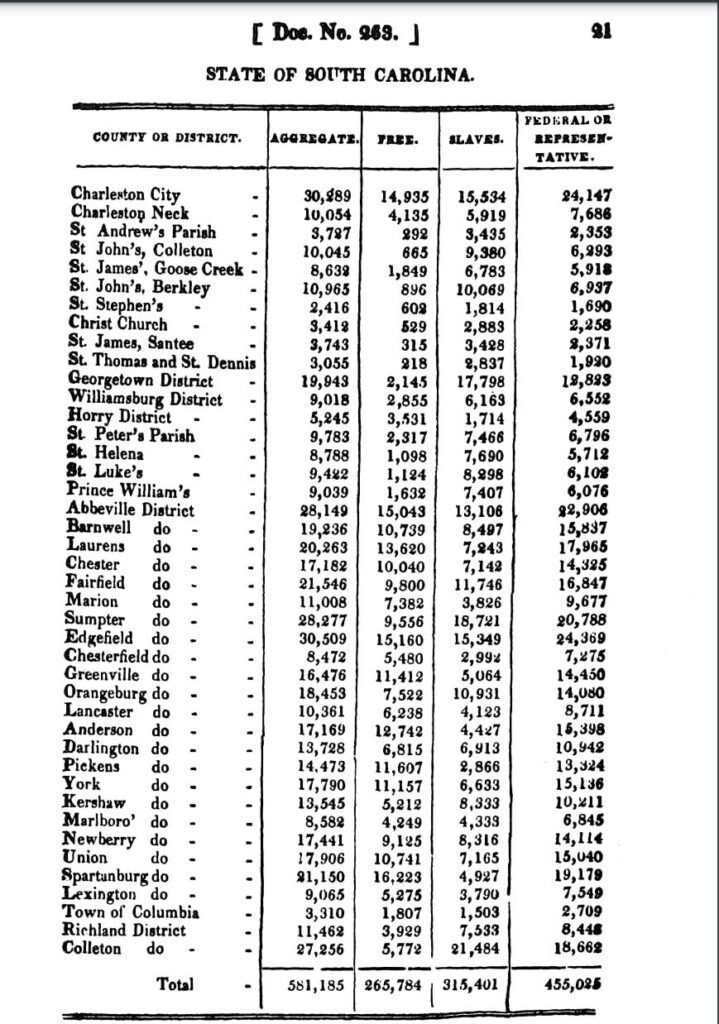

- All 16 Primary ResourcesThe Census of 1830

This abstract of the Census from 1830 not only provides numbers, state by state, of free and enslaved persons – but students will note that there are enslaved persons in many of the states they consider “free” (sample pages at left).

Note that the terminology is historically accurate but might be offensive to students unless context is provided (this will be true for many of the documents from this era).

CitePrintSharehttps://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1830/1830b.pdf

ORIIN, DUFF. “1830 Census - Full Document.” Census.gov, https://www2.census.gov/library/publications/decennial/1830/1830b.pdf.

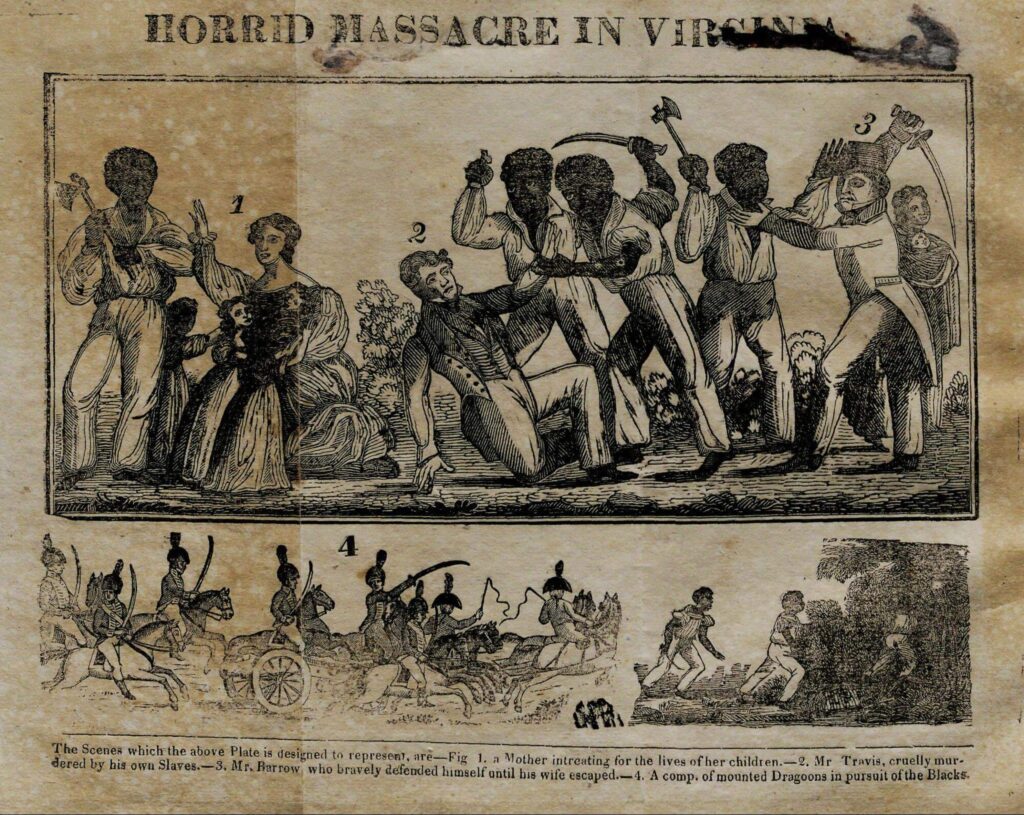

Nat Turner’s Rebellion, 1831Transcript“Even though Turner and his followers had been stopped, panic spread across the region. In the days following the attack, 3000 soldiers, militia men, and vigilantes killed more than one hundred suspected rebels. …Nat Turner’s rebellion led to the passage of a series of new laws. The Virginia legislature actually debated ending slavery, but chose instead to impose additional restrictions and harsher penalties on the activities of both enslaved and free African Americans. Other slave states followed suit, restricting the rights of free and enslaved blacks to gather in groups, travel, preach, and learn to read and write.” (Gilder Lehrman, link at right.)

Nat Turner’s Rebellion led to both public debate and a tightening of laws and policies. “Nat Turner was an enslaved man who had learned to read and write and become a religious leader despite his enslavement; following what he took to be religious signs, he led other enslaved people in an armed uprising. The violence of the uprising and Turner’s ability to escape and hide for approximately six weeks following the event led to changes in laws and policies and also led to a widespread climate of fear among white slaveholders. Enslaved people in far-flung states who had no connection to the event were lynched by white mobs. The State of Virginia briefly considered ending the practice of slavery in the wake of the rebellion, but they ultimately decided instead to tighten the laws of slavery.

1Africans in America/Part 3/Nat Turner's Rebellion. (n.d.). PBS. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/aia/part3/3p1518.html and Nat Turner - Rebellion, Death & Facts - HISTORY. (2021, January 26). History.com. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/nat-turnerCitePrintShareAllyn, Nelson. “Nat Turner's Rebellion, 1831 | Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History.” Gilder Lehrman Institute of American History |, https://www.gilderlehrman.org/history-resources/spotlight-primary-source/nat-turner%E2%80%99s-rebellion-1831.

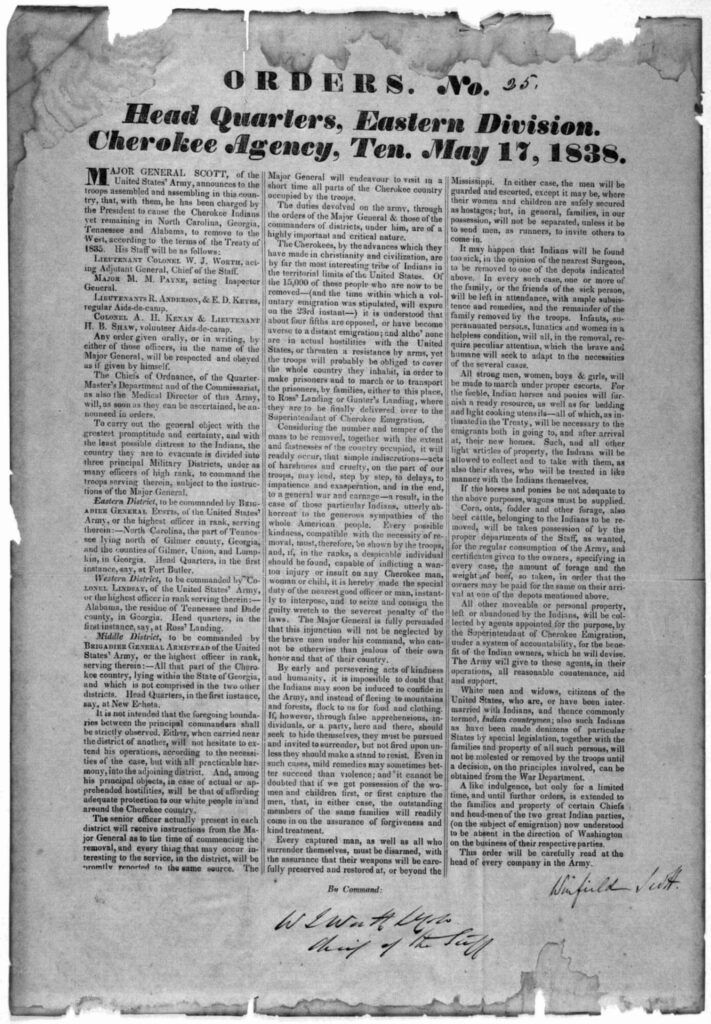

Orders pursuant to the Indian Removal Act of 1830 (Trail of Tears)Orders pursuant to the Indian Removal Act of 1830 (Trail of Tears)While the Trail of Tears and “Indian Removal Act” are not central to understanding slavery, they are critical events in the history of the country in this era; in addition, the concept of “indian removal” connects directly to tensions that rose as the nation expanded in both population and territory.

As the United States acquired Western territories, and as the power battle between slaveholding and free states continued, the land on which Native nations lived became increasingly valuable. After President Andrew Jackson signed the Indian Removal Act of 1830, the Choctaw, Creek, and Cherokee nations were forced to move from their land, most often on foot and with the deaths of many people, into Western territories. The 1838 forced removal of the Cherokee people from their Georgia land led to the deaths of thousands of people (exact numbers are unknown, but estimates range around 4,000 - 5,000.)

1- History & Culture - Trail Of Tears National Historic Trail (US National Park Service). (2020, July 10). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/trte/learn/historyculture/index.htm and Trail of Tears: Indian Removal Act, Facts & Significance - HISTORY. (2020, July 7). History.com. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.history.com/topics/native-american-history/trail-of-tears

CitePrintShare“Tile.loc.gov.” Library of Congress, https://tile.loc.gov/storage-services/service/rbc/rbpe/rbpe17/rbpe174/1740400a/1740400a.pdf.

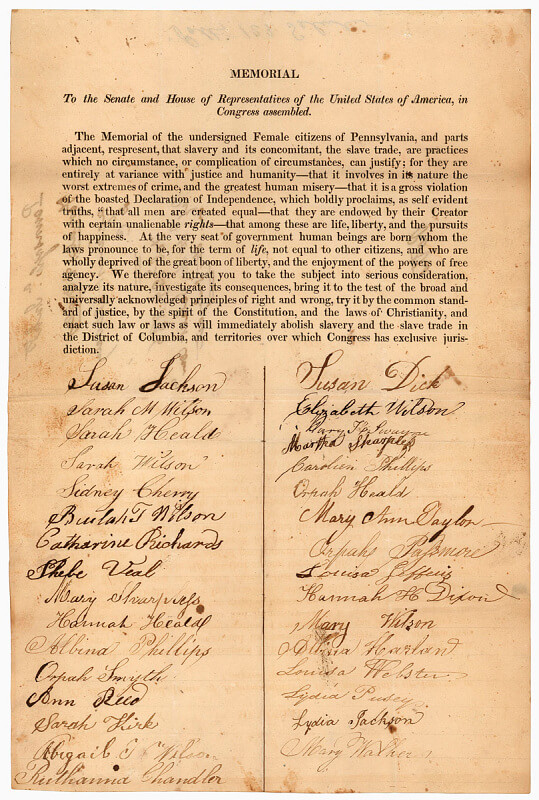

The Gag Rule, 1836“On May 26, 1836, the House of Representatives adopted a ‘Gag Rule’ stating that all petitions regarding slavery would be tabled without being read, referred, or printed….The enactment of the Gag Rule, rather than discouraging petitioners, energized the anti-slavery movement to flood the Capitol with written demands. Activists held up the suppression of debate as an example of the slaveholding South’s infringement of the rights of all Americans.”

CitePrintShareAdams, John Quincy. “The Gag Rule | National Museum of American History.” National Museum of American History, https://americanhistory.si.edu/democracy-exhibition/beyond-ballot/petitioning/gag-rule.

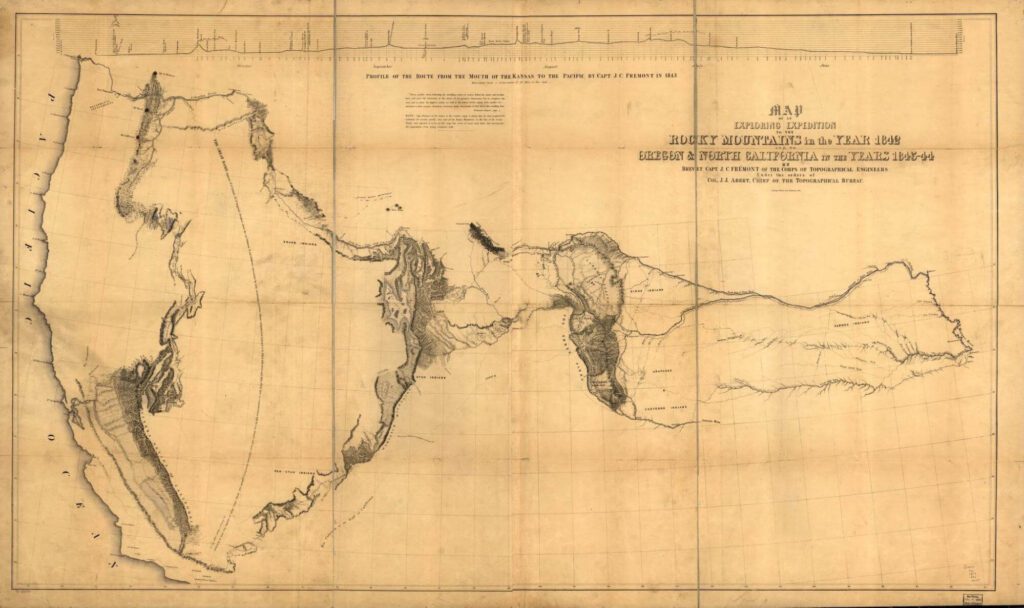

Map of Westward Expedition and Expansion, 1842-44Map of an exploring expedition to the Rocky Mountains in the year 1842 and to Oregon & north California in the years 1843-44As the nation expanded Westward, tensions rose further over whether new states and territories would permit or prohibit slavery.

CitePrintShareMap of an Exploring Expedition to the Rocky ... - Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/g4051s.ct000909/.

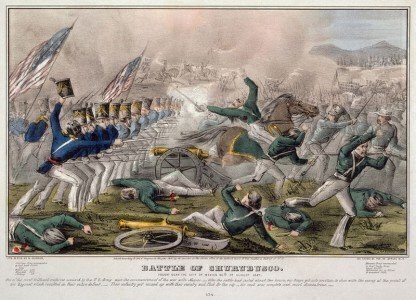

Battlefield Painting, Mexican-American WarBattlefield Painting, Mexican-American War“The pact set a border between Texas and Mexico and ceded California, Nevada, Utah, New Mexico, most of Arizona and Colorado, and parts of Oklahoma, Kansas, and Wyoming to the United States. …the acquisition of so much territory with the issue of slavery unresolved lit the fuse that eventually set off the Civil War in 1861.”

CitePrintShare“The Mexican-American war in a nutshell.” National Constitution Center, 13 May 2021, https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/the-mexican-american-war-in-a-nutshell.

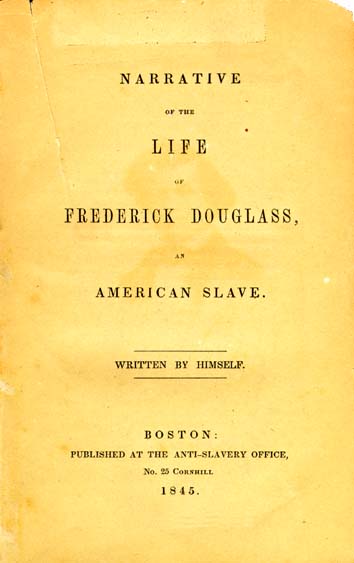

Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, excerpt, 1845TranscriptCHAPTER I. I WAS born in Tuckahoe, near Hillsborough, and about twelve miles from Easton, in Talbot county, Maryland. I have no accurate knowledge of my age, never having seen any authentic record containing it. By far the larger part of the slaves know as little of their ages as horses know of theirs, and it is the wish of most masters within my knowledge to keep their slaves thus ignorant. I do not remember to have ever met a slave who could tell of his birthday. They seldom come nearer to it than planting-time, harvest-time, cherry-time, spring-time, or fall-time. A want of information concerning my own was a source of unhappiness to me even during childhood. The white children could tell their ages. I could not tell why I ought to be deprived of the same privilege. I was not allowed to make any inquiries of my master concerning it. He deemed all such inquiries on the part of a slave improper and impertinent, and evidence of a restless spirit. The nearest estimate I can give makes me now between twenty-seven and twenty-eight years of age. I come to this, from hearing my master say, some time during 1835, I was about seventeen years old.

Students would benefit from reading an excerpt of the text of Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass – but in addition, the cover itself is an interesting artifact, and students can discuss its details and its possible impact upon publication in 1845. (See also text in this chart, below, from Frederick Douglass’ July 4 address in 1852.)

CitePrintShareHempel, Carlene, et al. “Frederick Douglass, 1818-1895. Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass, an American Slave. Written by Himself.” Documenting the American South, https://docsouth.unc.edu/neh/douglass/douglass.html.

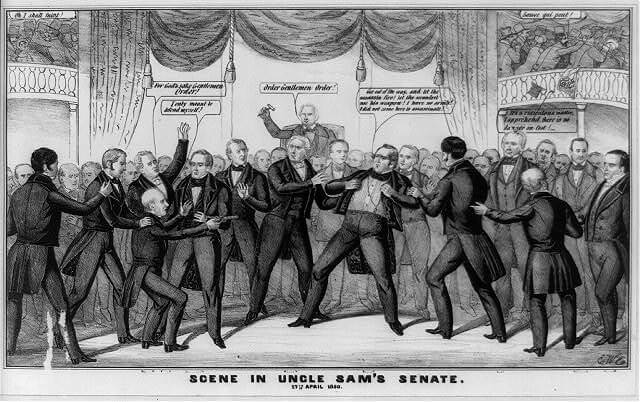

Scene in Uncle Sam’s Senate, 1850“Scene in Uncle Sam's Senate.Transcript"A somewhat tongue-in-cheek dramatization of the moment during the heated debate in the Senate over the admission of California as a free state when Mississippi senator Henry S. Foote drew a pistol on Thomas Hart Benton of Missouri.”

As new states were added to the nation, the question of how many would permit slavery and how many would prohibit it – and, therefore, which faction had more power – continued to contribute to growing tension.

CitePrintShare“Scene in Uncle Sam's Senate. 17th April 1850.” The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/2008661528/.

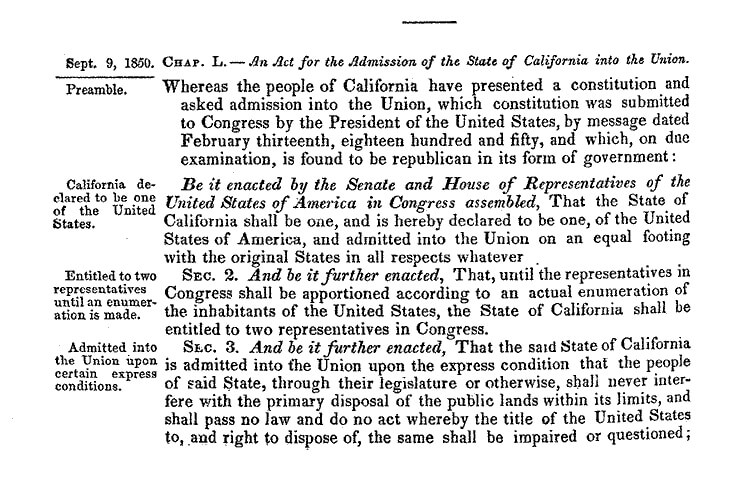

An Act for the Admission of the State of California into the Union, 1850CitePrintShareA Century of Lawmaking for a New Nation: U.S. Congressional Documents and Debates, 1774 - 1875, https://memory.loc.gov/cgi-bin/ampage?collId=llsl&fileName=009%2Fllsl009.db&recNum=479.

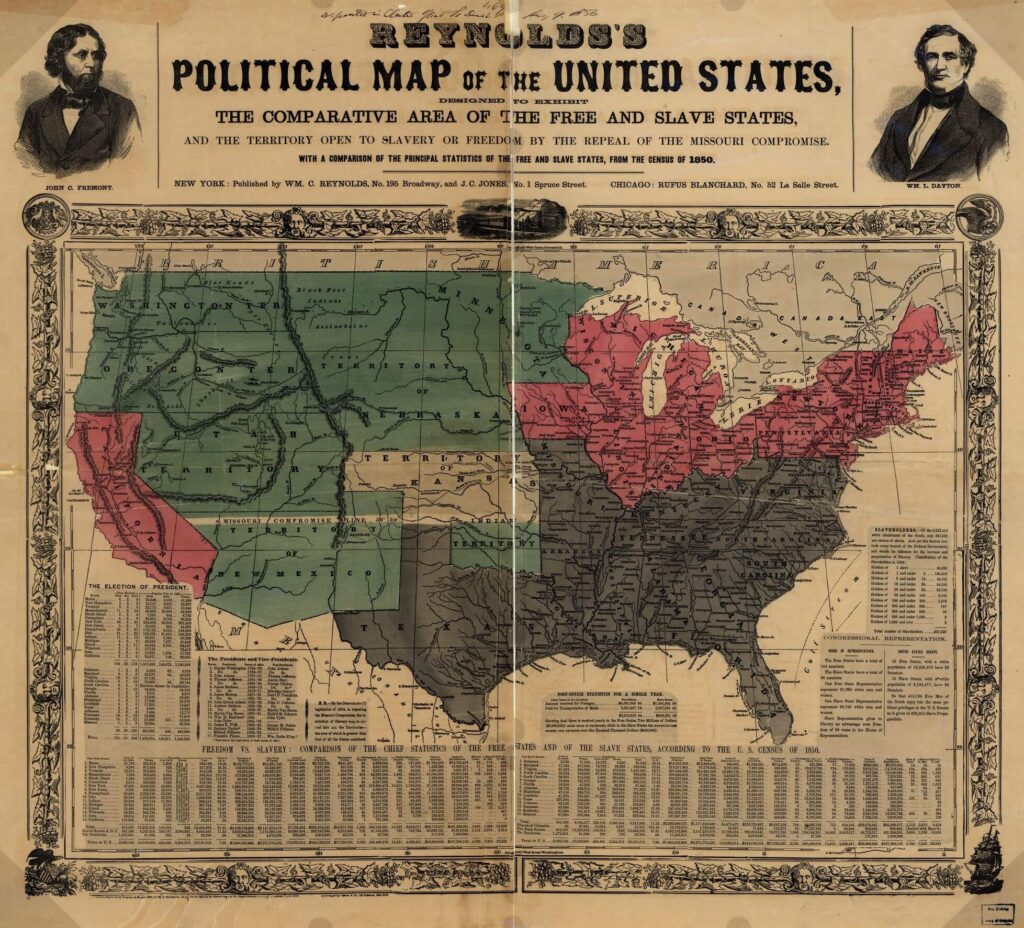

Political Map of the United States in 1850Political map of the United States in 1850This map has a range of valuable information, not only about Presidential politics, but also about population statistics and slavery. It makes a particular point of comparison with the 1830 Census, hyperlinked above in this chart.

CitePrintShare“1850 Political Map of the United States - History.” U.S. Census Bureau, 9 December 2021, https://www.census.gov/history/www/reference/maps/1850_political_map_of_the_united_states.html.

Frederick Douglass, “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”, 1852Douglass raises critical questions about patriotism, citizenship, and the nation’s ideals in this address. The text highlights issues that will continue to be points of tension not only at the start of the Civil War, but throughout Reconstruction (and, truly, throughout American history).

“I say it with a sad sense of the disparity between us. I am not included within the pale of glorious anniversary! Your high independence only reveals the immeasurable distance between us. The blessings in which you, this day, rejoice, are not enjoyed in common. The rich inheritance of justice, liberty, prosperity and independence, bequeathed by your fathers, is shared by you, not by me. The sunlight that brought light and healing to you, has brought stripes and death to me. This Fourth July is yours, not mine. You may rejoice, I must mourn.”

- Frederick Douglass, July 5, 1852CitePrintShareJuly 5, 1852, Frederick Douglass keynote address at an Independence Day celebration: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”

“A Nation's Story: “What to the Slave is the Fourth of July?”” National Museum of African American History and Culture, 3 July 2018, https://nmaahc.si.edu/explore/stories/nations-story-what-slave-fourth-july.

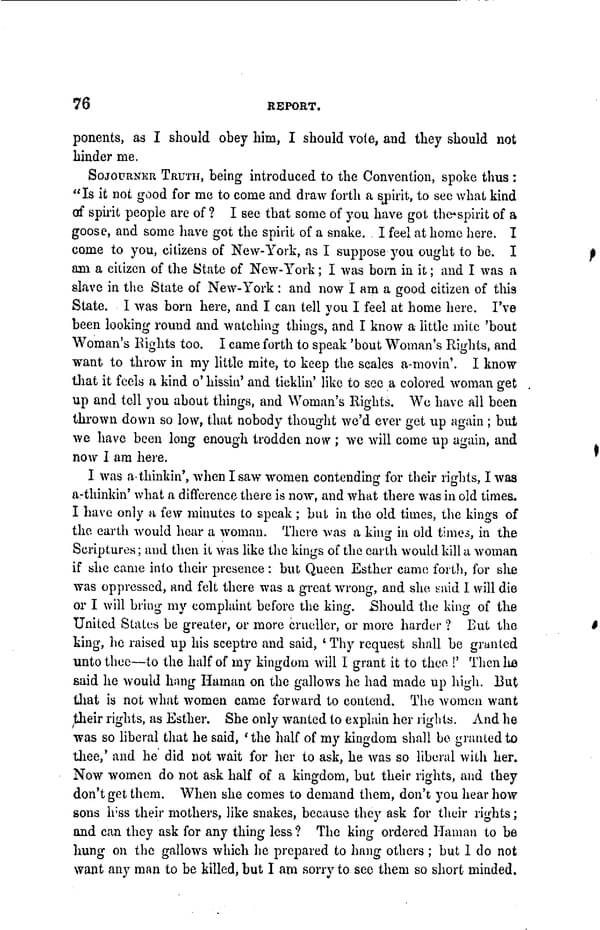

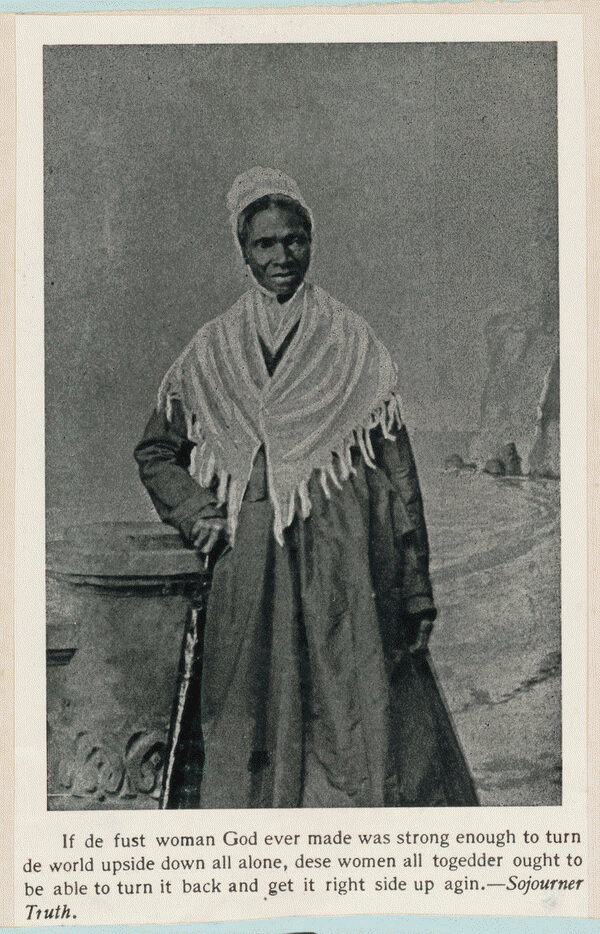

Sojourner Truth, Photograph and Speech at the Women’s Rights Convention, 1853See above; understanding the life and words of Sojourner Truth helps students to understand the complexity and intersectionality of both the women’s rights movement and the abolitionist movement.

CitePrintShareTitle Proceedings of the Woman's Rights Convention held at the Broadway Tabernacle, in the city of New York, on Tuesday and Wednesday, Sept. 6th and 7th, 1853.

Summary Sojourner Truth addresses the convention.

Image 76 of Susan B. Anthony Collection Copy | Library of Congress. https://www.loc.gov/resource/rbnawsa.n8289/?sp=76.

“Bleeding Kansas,” 1858“The years of 1854-1861 were a turbulent time in Kansas territory. The Kansas-Nebraska Act of 1854 …allowed the residents of these territories to decide by popular vote whether their state would be free or slave. This concept of self-determination was called popular sovereignty'. …Three distinct political groups occupied Kansas: pro-slavers, free-staters and abolitionists. Violence broke out immediately between these opposing factions and continued until 1861 when Kansas entered the Union as a free state on January 29th. This era became forever known as ‘Bleeding Kansas’.” (National Park Service, link at right.)

CitePrintShare“Bleeding Kansas - Fort Scott National Historic Site (US National Park Service).” National Park Service, 23 April 2020, https://www.nps.gov/fosc/learn/historyculture/bleeding.htm.

Abraham Lincoln, “A House Divided” Speech, 1858This excerpt from (or the entirety of) Lincoln’s address to the Republican State Convention puts the notion of “a house divided” in its original context, just before the start of the Civil War.

NOTE: Because it provides the central concept of this set of resources, I’ve included it last (although it predates John Brown’s speech above.)

Illinois Republican State Convention, Springfield, Illinois June 16, 1858Abraham Lincoln

Mr. President and Gentlemen of the Convention. If we could first know where we are, and whither we are tending, we could better judge what to do, and how to do it.

We are now far into the fifth year, since a policy was initiated, with the avowed object, and confident promise, of putting an end to slavery agitation. Under the operation of that policy, that agitation has not only, not ceased, but has constantly augmented.

In my opinion, it will not cease, until a crisis shall have been reached, and passed -

"A house divided against itself cannot stand."

I believe this government cannot endure, permanently half slave and half free.

I do not expect the Union to be dissolved - I do not expect the house to fall - but I do expect it will cease to be divided. It will become all one thing, or all the other.

1- John Brown's Raid (US National Park Service). (2021, July 30). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/articles/john-browns-raid.htm

- John Brown's Raid on Harper's Ferry. (n.d.). Ohio History Central. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://ohiohistorycentral.org/w/John_Brown%27s_Raid_on_Harper%27s_Ferry

CitePrintShare“House Divided Speech - Lincoln Home National Historic Site (US National Park Service).” National Park Service, 10 April 2015, https://www.nps.gov/liho/learn/historyculture/housedivided.htm.

An excerpt from John Brown's address to the court after hearing his guilty verdict, 1859John Brown’s raid on Harper’s Ferry fits into Lincoln’s foretelling of a crisis and further spurs the start of the Civil War. Brown’s speech to the courtroom highlights his sense of what, in this moment, constitutes justice and injustice.

John Brown’s Raid on Harper’s Ferry: John Brown, an abolitionist, led the Raid on Harper’s Ferry, a federal arsenal, in an effort to start an armed insurrection against slavery. The event, which took place after Lincoln’s “a house divided” speech, serves as an example of the violence Lincoln foretold. Brown echoed Lincoln’s sentiments, explaining in 1859, “I, John Brown, am now quite certain that the crimes of this guilty land will never be purged away but with blood. I had, as I now think, vainly flattered myself that without very much bloodshed it might be done.” Brown and his followers were trapped and arrested, and Brown was tried and found guilty of treason.

“I have, may it please the court, a few words to say. In the first place, I deny everything but what I have all along admitted--the design on my part to free the slaves. I intended certainly to have made a clean thing of that matter, as I did last winter when I went into Missouri and there took slaves without the snapping of a gun on either side, moved them through the country, and finally left them in Canada. I designed to have done the same thing again on a larger scale. That was all I intended. I never did intend murder, or treason, or the destruction of property, or to excite or incite slaves to rebellion, or to make insurrection.I have another objection; and that is, it is unjust that I should suffer such a penalty. Had I interfered in the manner which I admit...had I so interfered in behalf of the rich, the powerful, the intelligent, the so-called great, or in behalf of any of their friends--either father, mother, brother, sister, wife, or children, or any of that class--and suffered and sacrificed what I have in this interference, it would have been all right; and every man in this court would have deemed it an act worthy of reward rather than punishment.”

CitePrintShare“An excerpt from John Brown's address to the court after hearing his guilty verdict, 1859.” Digital Public Library of America, https://dp.la/primary-source-sets/john-brown-s-raid-on-harper-s-ferry/sources/1722.

The Women’s Rights Convention of 1853TranscriptQuotation beneath the photograph: "If de fust woman God ever made was strong enough to turn de world upside down all alone, dese women all togedder ought to be able to turn it back and get it right side up agin."

This photograph pairs with the text in the row below from the Women’s Rights Convention of 1853, when Sojourner Truth spoke to the group.

The Women’s Rights Convention: The Seneca Falls Convention of 1848 is a significant event in the fight for women’s rights and for women’s suffrage, though activists at the convention itself debated whether suffrage should be the center point of their platform. In addition, the Seneca Falls Convention is now widely understood to represent some tension between the women’s rights movement and the abolitionist movement; some activists at the time felt that the right to vote should not go to black men before white women. In this collection of documents, Sojourner Truth’s speech to a smaller, subsequent convention – one held in New York in 1853 – is included, largely because of the critical role Sojourner Truth plays in demonstrating the importance of the intersectionality of both the women’s rights and abolitionist movements.

1- On this day, the Seneca Falls Convention begins. (2021, July 19). National Constitution Center. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://constitutioncenter.org/blog/on-this-day-the-seneca-falls-convention-begins and More Women's Rights Conventions - Women's Rights National Historical Park (US National Park Service). (n.d.). National Park Service. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.nps.gov/wori/learn/historyculture/more-womens-rights-conventions.htm and Proceedings of the Woman's Rights Convention held at the Broadway Tabernacle, in the city of New York, on Tuesday and Wednesday, Sept. 6th and 7th, 1853. (n.d.). Library of Congress. Retrieved March 20, 2022, from https://www.loc.gov/item/93838289/

CitePrintShare“Sojourner Truth.” The Library of Congress, https://www.loc.gov/item/rbcmiller001306/.

Education for American Democracy

The War of 1812 is often referred to our country’s second war of independence. As a young nation, the United States' economy, territory, and rights of individual citizens were again threatened by the British. A Sailor’s Life for Me! presents life at sea during the War of 1812 for those serving aboard USS Constitution, one of the few naval vessels in America’s young navy, and now a national symbol, through interactive games, primary sources, and Museum resources.

The Roadmap

USS Constitution Museum

A Visual History, 1940–1963: Political Cartoons by Clifford Berryman and Jim Berryman presents 70 political cartoons that invite students to explore American history from the early years of World War II to the civil rights movement. These images, by father-and-son cartoonists Clifford Berryman and Jim Berryman, highlight many significant topics, including WWII and its impact, the Cold War, the space race, the nuclear arms race, and the struggle for school desegregation.

The Roadmap

National Archives Center for Legislative Archives

America and the World presents 63 political cartoons by Clifford K. Berryman that invite students to discuss American foreign policy from the Spanish American War to the start of World War II. This eBook presents a selection of cartoons that show Berryman’s insight into the people, institutions, issues, and events that shaped an important era of American history.

The Roadmap

National Archives Center for Legislative Archives

In this lesson, students explore the motives, pressures, and fears that shaped Americans’ responses to Nazism and the humanitarian refugee crisis it provoked during the 1930s and 1940s.

The Roadmap

Facing History and Ourselves

This unit plan deeply explores the motives, pressures, and fears that shaped Americans’ responses to Nazism and the humanitarian refugee crisis it provoked during the 1930s and 1940s. Students will examine why widespread American sympathy for the plight of Jewish refugees never translated into widespread support for prioritizing their rescue.

The Roadmap

Facing History and Ourselves

In 1898, the U.S. officially annexed Hawaii—but did Hawaiians support this? In this lesson, students read two newspaper articles, both hosted on the website Chronicling America, which make very different arguments about Hawaiians' support for—or opposition to—annexation. Students focus on sourcing as they investigate the motivations and perspectives of both papers and why they make very different claims.

The Roadmap

Stanford History Education Group

The unit contains three case studies all focusing on immigration policies: Chinese Exclusion Act, Hart Celler Act and DACA

The Roadmap

Smithsonian National Museum of American History

Go on a virtual field trip to the Museum of the American Revolution with Lauren Tarshis, author of the I Survived... books! You'll go behind the scenes to meet a museum curator and a museum educator, to examine real and replica artifacts, and to learn stories of real people - including kids and teens - who lived during this dynamic time. This program is presented in partnership with Scholastic, Inc.

The Roadmap

Museum of the American Revolution

Although different in many ways, antisemitism in Nazi Germany during the 1930s and anti-Black racism in Jim Crow-era America deeply affected communities in these countries. While individual experiences and context are unique and it is important to avoid comparisons of suffering, looking at these two places in the same historical period raises critical questions about the impact of antisemitism and racism in the past and present.

The Roadmap

United States Holocaust Memorial Museum